For years Christopher Tolkien, son of J.R.R. Tolkien, has been doing the world a service by issuing works of his father’s that have not been published yet or that were not completed (he has edited many of Tolkien’s incomplete works). As executor of the Tolkien estate, Christopher, now eighty-nine years old, has done yeoman’s work.

For years Christopher Tolkien, son of J.R.R. Tolkien, has been doing the world a service by issuing works of his father’s that have not been published yet or that were not completed (he has edited many of Tolkien’s incomplete works). As executor of the Tolkien estate, Christopher, now eighty-nine years old, has done yeoman’s work.

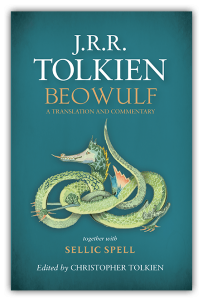

It was truly exciting to hear earlier this year that Christopher would be publishing his father’s translation of Beowulf. There was some very helpful and interesting press surrounding the publication, for instance here, here, here, here, and here. When it came out recently and I went to the bookstore to pick up a copy for myself (as a Father’s Day gift from my wife and daughter) and for my father (as a Father’s Day gift from me), I could hardly wait to get into it. I read it to my wife, as is our custom, and we have only just finished it.

This work contains Tolkien’s complete prose translation of Beowulf. He had completed around six hundred lines of an alliterative verse translation as well, and many were hoping that the new publication would contain both, but it only contains the prose rendition. It is difficult to understand why the incomplete verse translation was not included as well, especially as this work also contains Tolkien’s notes and commentary on Beowulf as well as his own Sellic Spell.

Furthermore, what is a significant publishing story without some drama? There apparently was some drama behind the scenes of getting all of this to press. This involved Professor Michael Drout, Professor of Old English at Wheaton College, who was working on the Tolkien translations before they were taken back by Christopher and the Tolkien Estate after what appears to have been a misunderstanding. That strange tale can be read about here with some of Dr. Drout’s follow-up thoughts about the new translation here.

As for the prose translation itself, I can only comment as a layman and a general reader. In short, my wife and I absolutely loved it. There are sections that soar with exhilarating heroism. The language can, at times, feel a bit stilted, but it was completed in 1926 and was never really completed at that. Tolkien did not intend to have it published, as far as can be told, and these factors should be kept in mind. Even so, it is a profoundly impressive work. Purists do not appear to like the prose, but I daresay this will be one of those cases when the readership is divided between those who simply want to appreciate a fascinating tale well-told by a more than capable translator and those looking for a substantial contribution to Beowulf scholarship. Those in the latter camp appear to be assuaged more by Tolkien’s learned commentary on the translation than by the provided translation.

As I say, this is an extremely enjoyable work. I was struck by how very much Beowulf obviously influenced the world of Middle Earth, even, at times, down to the direct borrowing of names in a couple of cases. Tolkien is at his best in some of the protracted speeches, as in Beowulf’s moving declaration that he will conquer Grendel. It is also intriguing to see the suggestions of C.S. Lewis on various points, as reflected in the notes.

It is a sign of Tolkien’s genius that an early project he deemed worthy of tossing into a drawer and essentially forgetting would turn out to be such an enjoyable and enthralling read. I do hope that Beowulf purists and scholars will appreciate how, at the end of the day, the appearance of this work will lead many people to consider the epic story of the great hero Beowulf either again or for the first time. At the end of the day, the story is more important than the scholarly community surrounding it…though I readily recognize that the scholarly community serves a critical role as stewards of the story and its world.

Read Tolkien’s Beowulf!