Like seemingly countless numbers of others, I can say that the Biltmore House in Asheville, NC, holds a very dear place in my heart and in my wife’s heart. We honeymooned in Asheville almost 20 years and, since that time, have returned to the grounds of Biltmore numerous times. I can certainly say that I have been affected by the charm of Biltmore and, while I do not necessarily take the entire tour of the house when I return these days, I love going back.

Like seemingly countless numbers of others, I can say that the Biltmore House in Asheville, NC, holds a very dear place in my heart and in my wife’s heart. We honeymooned in Asheville almost 20 years and, since that time, have returned to the grounds of Biltmore numerous times. I can certainly say that I have been affected by the charm of Biltmore and, while I do not necessarily take the entire tour of the house when I return these days, I love going back.

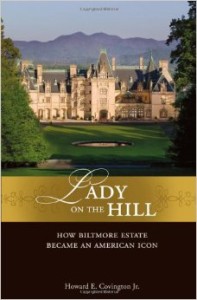

The last time I was at Biltmore was in August of this year. While there I picked up Howard Covington’s Lady on the Hill. I’m very glad I did! The book is less a straight history of the house (though it is a history) than an exploration of how this grand home and estate passed from being the personal home of George Vanderbilt in the late 19th/early 20th century to being what it is today: one of America’s most famous homes, a privately owned, highly successful tourist destination that attracts thousands of people every year with its charming preservation of Vanderbilt’s original vision in ways that are classic but also unique and fresh.

Dominating this particular angle of the Biltmore story is the character of William Cecil, George Vanderbilt’s grandson and the primary figure in transitioning the house from a glorious but aging money-pit to the astonishing success story that it is today. Cecil’s story is one of a fierce determination to keep the house in the hands of the family, to make it profitable so that he could preserve it as it should be preserved, and to open it to all who would like to come to America’s home.

It is a story of preservation but also innovation. Cecil refused to change the house into a museum. He was determined that people who visited should see it as it was intended to be: a home. This approach, as well as Cecil’s unapologetic intention that the house be profitable (so that, again, he could preserve it as it should be preserved), ran him afoul of the conservative preservationist community who essentially accused Cecil of being more influenced by Walt Disney than America’s other great home preservationists. Cecil responded by remaining faithful to his convictions and to his unorthodox but ultimately triumphant vision for what the house and grounds could be.

The book is well written and engaging. Those who have visited the house will find many of the details fascinating. Above all, the enthralling backstory of how Biltmore came to be what it is today will provide visitors with a profound appreciation for the genius and vision of a number of people, but, preeminently, of George Vanderbilt (of course) and his grandson William Cecil.

The book should also be read by leaders. Cecil is a case study in what can happen when a person is governed by clear thinking, fierce determination, and the compelling power of conviction. These qualities could lead Cecil to be prickly at times, but it seems clear that none who encountered him failed to appreciate his resolve and grit. These qualities also led Cecil to accomplish what he did: the preservation and opening and continuance of one of America’s most beloved homes.

If you have visited Biltmore, this is a must-read. If you have not but intend to, this book will well-prepare you to appreciate deeply what you are experiencing at Biltmore when you go.

Cool. I shall put this on my reading list.