1 All the congregation of the people of Israel moved on from the wilderness of Sin by stages, according to the commandment of the Lord, and camped at Rephidim, but there was no water for the people to drink. 2 Therefore the people quarreled with Moses and said, “Give us water to drink.” And Moses said to them, “Why do you quarrel with me? Why do you test the Lord?” 3 But the people thirsted there for water, and the people grumbled against Moses and said, “Why did you bring us up out of Egypt, to kill us and our children and our livestock with thirst?” 4 So Moses cried to the Lord, “What shall I do with this people? They are almost ready to stone me.” 5 And the Lord said to Moses, “Pass on before the people, taking with you some of the elders of Israel, and take in your hand the staff with which you struck the Nile, and go. 6 Behold, I will stand before you there on the rock at Horeb, and you shall strike the rock, and water shall come out of it, and the people will drink.” And Moses did so, in the sight of the elders of Israel. 7 And he called the name of the place Massah and Meribah, because of the quarreling of the people of Israel, and because they tested the Lord by saying, “Is the Lord among us or not?” 8 Then Amalek came and fought with Israel at Rephidim. 9 So Moses said to Joshua, “Choose for us men, and go out and fight with Amalek. Tomorrow I will stand on the top of the hill with the staff of God in my hand.” 10 So Joshua did as Moses told him, and fought with Amalek, while Moses, Aaron, and Hur went up to the top of the hill. 11 Whenever Moses held up his hand, Israel prevailed, and whenever he lowered his hand, Amalek prevailed. 12 But Moses’ hands grew weary, so they took a stone and put it under him, and he sat on it, while Aaron and Hur held up his hands, one on one side, and the other on the other side. So his hands were steady until the going down of the sun. 13 And Joshua overwhelmed Amalek and his people with the sword. 14 Then the Lord said to Moses, “Write this as a memorial in a book and recite it in the ears of Joshua, that I will utterly blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven.” 15 And Moses built an altar and called the name of it, The Lord Is My Banner, 16 saying, “A hand upon the throne of the Lord! The Lord will have war with Amalek from generation to generation.”

There is a story behind the following picture that lends it more significance than we might otherwise imagine at first glance.

This is a picture of Theodore Roosevelt on the back of a train during his 1906 visit to the then-being-built Panama Canal. He had gone to Panama to see and inspect the work as well as to inspire the workers in their grueling and dangerous efforts to complete the canal. His visit was significant. It was the first time a sitting president of the United States had visited a foreign country while in office, so to say it created quite a stir would be an understatement.

In his amazing book, The Path Between the Seas, David McCullough writes of the effect that the sight of Roosevelt had upon many of those who saw him.

To the majority of those on the job his presence had been magical. Years afterward, the wife of one of the steam-shovel engineers, Mrs. Rose van Hardeveld, would recall, “We saw him . . . on the end of the train. Jan got small flags for the children, and told us about when the train would pass . . . Mr. Roosevelt flashed us one of his well-known toothy smiles and waved his hat at the children . . .” In an instant, she said, she understood her husband’s faith in the man.” And I was more certain than ever that we ourselves would not leave until it [the canal] was finished.” Two years before, they had been living in Wyoming on a lonely stop on the Union Pacific. When her husband heard of the work at Panama, he had immediately wanted to go, because, he told her, “With Teddy Roosevelt, anything is possible.” At the time neither of them had known quite where Panama was located.[1]

That strikes me as very interesting, perhaps because the modern American political landscape has engendered such skepticism among people that one wonders if the sight of any leader could actually inspire anything like hope in people today. It is also interesting because it points to, at least, the potential impact that a lone person can have on others. But even as I say that I realize it is too simplistic. What caused this wife to immediately take courage and have hope for the future was not Roosevelt per se, but what Roosevelt had come to represent: American ingenuity, resolve, determination, and strength. In other words, Roosevelt himself had become a symbol of greater realities, realities that contained what was necessary to lift embattled laborers out of despair and into new vistas of hope and optimism.

Symbols can do that. There mere sight of the right symbol can do that. I think we see this dynamic at work all throughout scripture. I believe we certainly see it at work in Exodus 17. The chapter contains two different stories that are united by common symbols: Moses and his hands and his staff. And, like all symbols, these encouraged the people by pointing to realities that far superseded a man and a staff.

God gave Israel a symbol that reminded them of past deliverance.

We begin, amazingly, with yet more complaints about water. Water has played a large part in the story of Exodus thus far, both on the far side of the Red Sea and, of course, through the Red Sea, and now on the promised land side as well.

1 All the congregation of the people of Israel moved on from the wilderness of Sin by stages, according to the commandment of the Lord, and camped at Rephidim, but there was no water for the people to drink. 2 Therefore the people quarreled with Moses and said, “Give us water to drink.” And Moses said to them, “Why do you quarrel with me? Why do you test the Lord?” 3 But the people thirsted there for water, and the people grumbled against Moses and said, “Why did you bring us up out of Egypt, to kill us and our children and our livestock with thirst?” 4 So Moses cried to the Lord, “What shall I do with this people? They are almost ready to stone me.” 5 And the Lord said to Moses, “Pass on before the people, taking with you some of the elders of Israel, and take in your hand the staff with which you struck the Nile, and go. 6 Behold, I will stand before you there on the rock at Horeb, and you shall strike the rock, and water shall come out of it, and the people will drink.” And Moses did so, in the sight of the elders of Israel. 7 And he called the name of the place Massah and Meribah, because of the quarreling of the people of Israel, and because they tested the Lord by saying, “Is the Lord among us or not?”

Yes, from the waters of the Nile, to the waters of the Red Sea, to the bitter waters of Marah, to the absence of water at Rephidim, water shows up again as both a necessity and a barrier. Above all, it (or its absence) shows up as an opportunity for the Lord God to prove once again his faithfulness.

The miracle at Rephidim is straight-forward enough: the children of Israel encamp, the children of Israel cry out for water, Moses, following the instructions of Yahweh God, strikes a rock and water gushes forth saving the life of God’s people yet again.

The IVP Bible Background Commentary rightly points out that “sedimentary rock is known to feature pockets where water can collect just below the surface. If there is some seepage, one can see where these pockets exist and by breaking through the surface can release the collected waters.” However, it also rightly goes on to say, “however, we are dealing with a quantity of water beyond what this explanation affords.”[2] We again see that naturalistic explanations will not work, even if God employed natural materials to work His wonders.

We see a pattern forming among the people of God: blessing – forgetfulness – complaint – rebuke – deliverance – blessing – etc. Time and time again we see this pattern or some variation of it. It is frustrating to observe, until, that is, we remember that we perpetuate this pattern in our own lives.

We are struck by the wonder of yet another miracle pointing to the glory of our great God. However, what stands out here is God’s instructions to Moses concerning how he was to approach the rock.

“Pass on before the people, taking with you some of the elders of Israel, and take in your hand the staff with which you struck the Nile, and go. 6 Behold, I will stand before you there on the rock at Horeb, and you shall strike the rock, and water shall come out of it, and the people will drink.”

There is an element of theater here that catches our attention. Moses is to (a) take his staff, (b) walk before the people, and (c) take with him some of the elders. He is then to (d) strike the rock with the same staff with which he had struck the Nile. This was also the same staff that Moses held over the waters of the Red Sea as God divided the waters and then returned the waters. We see this in Exodus 14.

15 The Lord said to Moses, “Why do you cry to me? Tell the people of Israel to go forward. 16 Lift up your staff, and stretch out your hand over the sea and divide it, that the people of Israel may go through the sea on dry ground.

21 Then Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, and the Lord drove the sea back by a strong east wind all night and made the sea dry land, and the waters were divided.

26 Then the Lord said to Moses, “Stretch out your hand over the sea, that the water may come back upon the Egyptians, upon their chariots, and upon their horsemen.” 27 So Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, and the sea returned to its normal course when the morning appeared. And as the Egyptians fled into it, the Lord threw the Egyptians into the midst of the sea. 28 The waters returned and covered the chariots and the horsemen; of all the host of Pharaoh that had followed them into the sea, not one of them remained. 29 But the people of Israel walked on dry ground through the sea, the waters being a wall to them on their right hand and on their left.

I am struck by these gestures that God repeatedly called upon Moses to employ and enact. After all, it was God working the miracle, not Moses, not his hands, and not his staff. So why ask Moses to act out these elements? There may be many reasons. Undoubtedly there is a certain element of leadership verification. God was thereby showing His own people that Moses was His divinely called instrument whom He was empowering to lead His children. Undoubtedly there was an element of clarification to Israel’s enemies as well. By allowing them to see that God was working through Moses, specifically, God was removing any temptation His enemies might have had of claiming that these events were simply freak occurrences.

There is something here about the abiding power of symbols and their importance in keeping God’s people focused and thinking clearly. At this point in the wilderness account, it is clear that Moses and his hands and staff had become symbols for the people of God. Simply put, they were symbols of God’s faithfulness, God’s might, God’s strength, and God’s love for His people.

Here at Rephidim, then, Moses walking before the people with his staff and his striking the rock was a way of reminding the people that the same God who turned the waters of the Nile to blood was the same God who divided the waters of Red Sea and was the same God who had turned the bitter waters of Marah sweet.

Thus, God was establishing among His people a symbol to remind them of past deliverance so that they would not lose heart in a time of present trial.

Of course, God has done the very same thing with His people today, the Church.

23 For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, 24 and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and said, “This is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” (1 Corinthians 11)

Bound up with all of this, of course, is the cross itself that the Church the world over has adopted as a symbol of the love and faithfulness of God.

God has left us physical symbols because Christians are not Gnostics. We do not consider all material creation to be evil. As physical beings, it is oftentimes through physical symbols that we are most helped to remember divine truths. Thus, the bread and the wine remind us, just as Moses and his staff reminded the Israelites, that God has not abandoned us, that God is with us, that God has not brought us into the wilderness to die of thirst, and that God will provide for His people.

Once again, God worked a miracle through Moses and his hands and his staff. At Rephidim, this miracle reminded the people. Then, on the heels of this great work, God called upon Moses and his hands and his staff to once more symbolize His divine power and majesty. This next miracle was occasioned by Israel’s first armed conflict since leaving Egypt.

God gave Israel a symbol that assured them of future victory.

Having provided miraculous waters, the Lord now moved to provide deliverance from an attacking army of Amalekites.

8 Then Amalek came and fought with Israel at Rephidim. 9 So Moses said to Joshua, “Choose for us men, and go out and fight with Amalek. Tomorrow I will stand on the top of the hill with the staff of God in my hand.”

The Amalekites were the descendants of Esau. They set upon the Israelites in the wilderness believing they could wipe out the wandering people. Of course, this was not to be. The Israelites were God’s people under divine commission to survive the wilderness and take back the land of promise. This meant that no army, be it the mighty army of Pharaoh or the undoubtedly less impressive but still dangerous army of the Amalekites, would conquer them. However, their victory still involved their obedience.

Moses called upon Joshua to act. This is the first time we meet Joshua. He was to play a crucial role in Israel’s eventual conquest of the land. Here, he is called upon to muster what troops he can to go and face the Amalekites. Tellingly, Moses said to him, “Tomorrow I will stand on the top of the hill with the staff of God in my hand.”

Here is the point of connection between the two stories: Moses, his hands, the staff, and the power of God. Tomorrow, Moses would once again be the instrument through which God would work. Peter Enns has pointed out something telling about the use of the word “tomorrow” in verse 9.

“Tomorrow” Moses will climb a “hill” with “the staff of God in [his] hand.”…Why wait until “tomorrow”? Throughout Exodus “tomorrow” represents the time in which God will act to punish Israel’s enemies. We saw this in the plague narrative (8:23,29; 9:5,18; 10:4). Most recently the word was used in 16:23 with respect to Israel’s gathering of bread on the sixth day in anticipation of the Sabbath. In other words, tomorrow is when something “big” happens. That the defeat of the Amalekites is to take place “tomorrow” signals to the reader that this is another redemptive event. It is a plague on another of Israel’s enemies.[3]

This is intriguing to be sure. Indeed, something “big” did happen on the morrow! Thus, Moses made preparations for the children of Israel to engage in its first war as a post-Egyptian-exile people. Old Testament scholar Douglas Stuart calls this conflict between Israel and the Amalekites “an example of Old Testament holy war.” He then offers twelve characteristics of holy war for Israel based on Deuteronomy 20:1-20 and other passages in the Old Testament. These characteristics are:

- No standing army was allowed.

- No pay for soldiers was permitted.

- No personal spoil/plunder could be taken.

- Holy war could be fought only for the conquest or defense of the promised land.

- Only at Yahweh’s call could holy war be launched.

- Solely through a prophet could that divine call come.

- Yahweh did the real fighting in holy war because the war was always His.

- Holy war was a religious undertaking, involving fasting, abstinence from sex, and/or other forms of self denial.

- A goal of holy war was the total annihilation of an evil culture.

- The violator of the rules of holy war became an enemy.

- Exceptions and mutations were possible, especially in the case of combat with those who were not original inhabitants of the promised land.

- Decisive, rapid victory characterized faithful holy war.[4]

These points describe the recurring pattern of Israel’s conflicts with it enemies in the wilderness wanderings and conquest, and deviations from these guidelines resulted in great catastrophe. But here Israel was faithful and the people of God were victorious and received God’s favor and blessings as our text recounts.

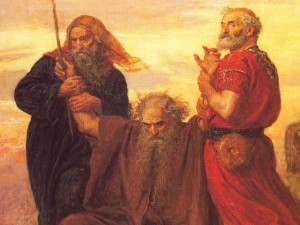

10 So Joshua did as Moses told him, and fought with Amalek, while Moses, Aaron, and Hur went up to the top of the hill. 11 Whenever Moses held up his hand, Israel prevailed, and whenever he lowered his hand, Amalek prevailed. 12 But Moses’ hands grew weary, so they took a stone and put it under him, and he sat on it, while Aaron and Hur held up his hands, one on one side, and the other on the other side. So his hands were steady until the going down of the sun. 13 And Joshua overwhelmed Amalek and his people with the sword. 14 Then the Lord said to Moses, “Write this as a memorial in a book and recite it in the ears of Joshua, that I will utterly blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven.” 15 And Moses built an altar and called the name of it, The Lord Is My Banner, 16 saying, “A hand upon the throne of the Lord! The Lord will have war with Amalek from generation to generation.”

Moses, standing upon a hill, led the children to victory. When his hands were raised, Israel triumphed. When he lowered them, the Amalekites began to win. Therefore two men, Aaron and Hur, helped keep his hands up. In so doing, they demonstrated once again that while the victory was wholly God’s, the symbolic means through which God worked His wonders mattered greatly. The hands needed to be raised.

Thus, the symbol of remembrance before the rock gushing water became also a symbol of victory, present and future, here on the hill above the raging battle. The same symbol therefore pointed backward and forward. It reminded and it anticipated.

Earlier we pointed to the Lord’s Supper as God’s final symbol of remembrance for His people. At Rephidim, God had established a symbol of past deliverance for grumbling Israel, just as, in the Supper, Christ established a symbol of remembrance for His beleaguered Church. Interestingly, the Lord’s Supper, like Moses and his hands and his staff, is also a symbol of present and future victory. Notice the anticipatory element in the words of institution concerning the wine.

25 In the same way also he took the cup, after supper, saying, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me.” 26 For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes. (1 Corinthians 11)

The Lord’s Supper is a symbol that we do over and over again “until he comes.” It is an act of remembrance and anticipation. The Church needs ever and again to be reminded of her Champion.

Israel knew that God was with them when they saw Moses upon the hill with his arms upraised.

The Church knows that God is with us when we see Jesus with His arms outstretched.

Moses’ upraised arms meant victory by might was assured.

Jesus’ outstretched arms mean that victory is assured by love, by forgiveness, and by obedience.

The cross is the living symbol of God’s presence, God’s mercy, God’s love, and God’s faithfulness.

There on the hill we still see the symbol of life for us: the cross upon which Jesus died. And we also see the empty tomb, reminding us that Jesus has overcome sin, death, and hell.

The people of God still need reminders that we have a Champion and that His arms are raised forever for us.

[1] McCullough, David (2001-10-27). The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914 (pp. 499-500). Simon & Schuster. Kindle Edition.

[2] John H. Walton, Victor H. Matthews and Mark W. Chavalas, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000), p.92.

[3] Peter Enns, Exodus. The NIV Application Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2000), p.346.

[4] Douglas K. Stuart, Exodus. Vol.2. The New American Commentary. New Testament, Vol.2 (Nashville, TN: Broadman and Holman, 2006), p.395-397.