As we continue with our consideration of the reliability of the Bible (with special attention being paid to the writings of the New Testament), I would like to review the premise and the three basic historical facts we looked at earlier.

As we continue with our consideration of the reliability of the Bible (with special attention being paid to the writings of the New Testament), I would like to review the premise and the three basic historical facts we looked at earlier.

The premise from which we are operating is as follows: the reliability of the Bible is important as it is from the Bible that we learn information about the person of Jesus: who He is, why He came, and what He has done and is doing.

We believe this is a matter of paramount importance. Can we trust what we read in our Bibles? Behind this specific consideration is the larger theological issue of revelation and the modern skepticism concerning the reality of it. But Christianity is a revealed religion, and, in fact, is the steward of the definitive revelation of God in Christ. It is through the teachings of the Bible that we learn about Christ. Thus, our confidence in scripture is our confidence in the revealed truth of God, or God’s word.

The three basic historical facts that will continue to frame our discussion are:

- The books of the New Testament were written. The original manuscripts are called “the autographs”

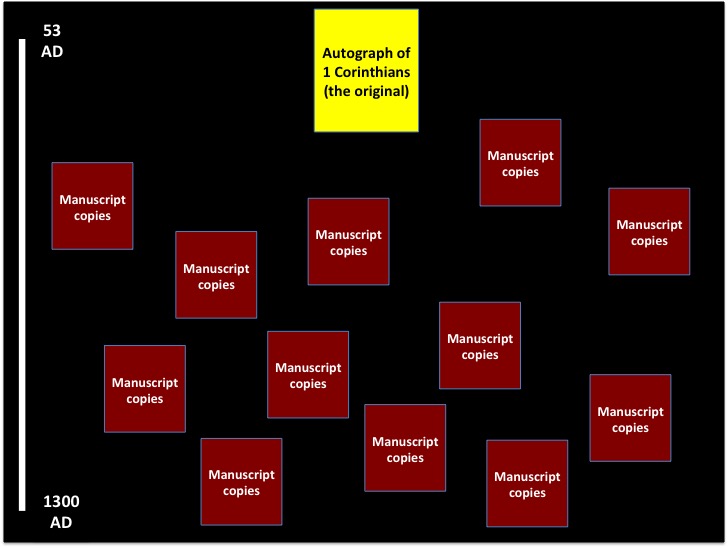

- Immediately, copies began to be made of the autographs and spread throughout the world. We refer to these as “the New Testament manuscripts.”

- In the year 367 AD, Athanasius, in his Festal Letter, provided the earliest known list of the 27 books of the New Testament as we know them.

We will be giving the first two facts particular attention.

No other ancient work has such a strong body of manuscript evidence as close to the time of its writing as does the Bible.

One of the significant arguments for the reliability of the Bible has to do with the manuscript evidence that we possess. In order to get at this, we will need to remember especially those first two facts. Let us use 1 Corinthians as a case study. First, let us realize that 1 Corinthians was written by Paul in the mid 50’s AD.

The original letter, the first edition of 1 Corinthians, is call “the autograph.” We do not possess it. We do not possess any of the New Testament autographs. However, what we do possess are numerous copies of the original letter.

So how do we know what 1 Corinthians says? Primarily by looking at the earliest manuscripts. The earliest manuscripts are usually given the greatest weight because they were copied closest to the time of the original writing. Then we look at all the manuscripts we have for 1 Corinthians, comparing them as we go. We also consider the writings of the earliest church fathers and how they referred to and quoted or paraphrased 1 Corinthians. In this way, we are able to see what the original said. The process is a lot more complicated, of course, and there are specialists in numerous fields that contribute to this process, but, in general, this is how we come to know what, say, 1 Corinthians says.

It has become fashionable for critics to harp on the fact that we only possess copies of the New Testament writings and not the originals. As we have already said, this is not terribly significant. Papyrus and other mediums do not last forever and the fact that the autographs have not survived is neither here nor there. Perhaps God in His wisdom knew that the Church would be tempted to make an idol of the original writings had they survived. And, of course, perhaps they have survived and have not yet been discovered. Exciting early manuscript finds happen all the time!

No, the truth is that, what we have with the New Testament and its manuscripts is, in the words of Dan Wallace, “an embarrassment of riches.”

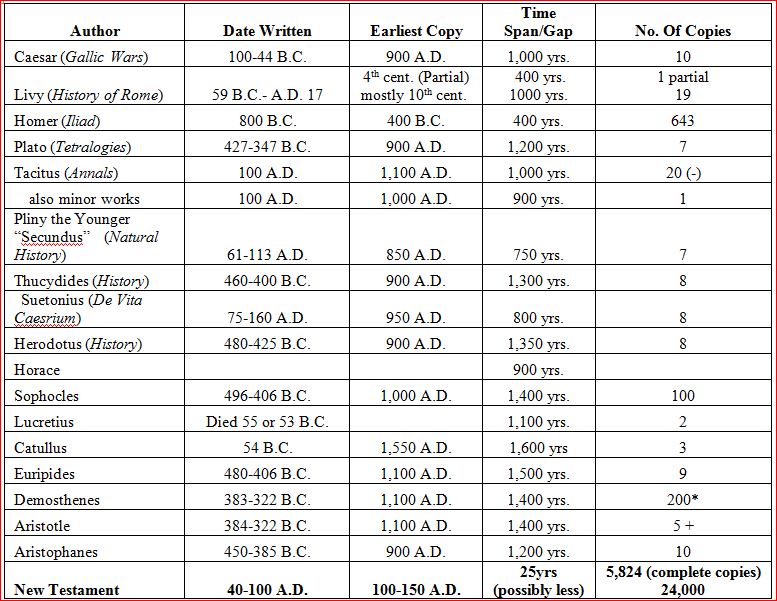

What does he mean by that? What he means is that the manuscripts we have for the books of the New Testament are so voluminous and are so much closer to the time of the writing of the biblical autographs than are the manuscripts for other ancient works that are generally trusted today that if we cannot trust the Bible, then we have much more reason not to trust these other works.

Let me demonstrate. Below is a series of ancient works. Their authors are listed as are the book/s they wrote, the date they were written, and the date of the earliest surviving copy we have for that book. We likewise possess none of the autographs, the originals, for any of these writings. Then the time gap between the date of the writing of the autograph and the date of the earliest manuscript is written along with the number of manuscripts we have for that work. Let us consider how the New Testament stacks up to these other works of antiquity.

An embarrassment of riches indeed! This is simply staggering. Let me share Dr. Wallace’s conclusion concerning this amazing comparison:

An embarrassment of riches indeed! This is simply staggering. Let me share Dr. Wallace’s conclusion concerning this amazing comparison:

In terms of extant manuscripts, the New Testament textual critic is confronted with an embarrassment of riches. If we have doubts about what the autographic New Testament said, those doubts would have to be multiplied at least a hundred-fold for the average classical author. And when we compare the New Testament manuscripts to the very best that the classical world has to offer, it still stands head and shoulders above the rest. The New Testament is far and away the best-attested work of Greek or Latin literature from the ancient world. Precisely because we have hundreds of thousands of variants and hundreds of early manuscripts, we are in an excellent position for recovering the wording of the original. Further, if the radical skeptics applied their principles to the rest of Greco-Roman literature, they would thrust us right back into the Dark Ages, where ignorance was anything but bliss. Their arguments only sound impressive in a vacuum.[1]

The late Frederic Kenyon, famed British paleographer and classical scholar, put it even more poignantly:

The interval then between the dates of original composition and the earliest extant evidence becomes so small as to be negligible, and the last foundation for any doubt that the Scriptures have come down to us substantially as they were written has now been removed. Both the authenticity and the general integrity of the books of the New Testament may be regarded as finally established.[2]

Church, marvel at the amazing evidence and the mountain of confirmation that God has left His people concerning the reliability of His word.

The variants in the manuscript copies are almost completely trivial.

But let us go back a moment to the autograph and the manuscript copies.

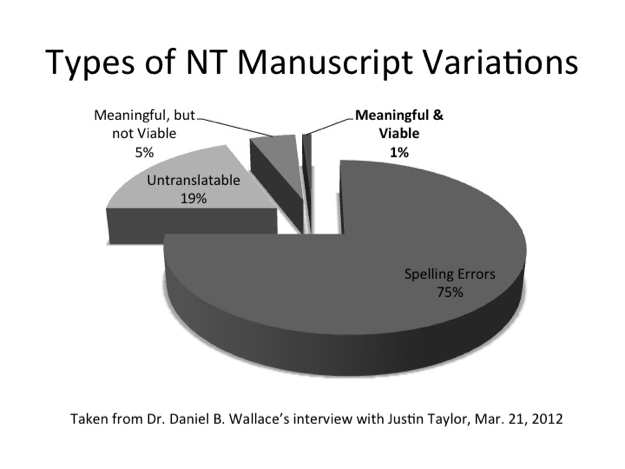

The next question is do the manuscript copies we have contain discrepancies between themselves? In other words, if we compare all of the copies do they all completely agree? And the answer is clearly no. There are discrepancies among the manuscripts.

Much is made of this fact by detractors of the Bible. Indeed, of all the arguments marshaled against scripture, this is one of the most common. It is asserted with confidence that since there are discrepancies among the manuscripts we therefore cannot know what the Bible says. But when this attack is made, those making it are really revealing their own biases and personal agendas.

In point of fact, discrepancies among the manuscripts do not matter and do not touch on the reliability of the Bible for two important reasons.

The first is that the doctrine of inerrancy, or the idea that the Bible has no errors, applies to the autographs, to what Paul or Matthew or John or whomever actually wrote, not to later copies. For instance, were I to ask all of you to open your Bibles to the little book of Philemon in the New Testament and then give you all pen and paper and ask you to copy the book of Philemon, I guarantee you there would be discrepancies in our copies. But the fact that you and I might have made mistakes in copying the book does not mean (a) that the book itself has errors or (b) that our errors make the original wording of the book unattainable.

The doctrine of inerrancy has always applied to the autographs. The classic evangelical statement on inerrancy is the 1978 “Chicago Statement on Inerrancy.” It is a very interesting and well-done statement that should be closely considered. A few of its affirmations and denials are especially apropos for our considerations.

Article VI. We affirm that the whole of Scripture and all its parts, down to the very words of the original, were given by divine inspiration.

Article X. We affirm that inspiration, strictly speaking, applies only to the autographic text of Scripture, which in the providence of God can be ascertained from available manuscripts with great accuracy. We further affirm that copies and translations of Scripture are the Word of God to the extent that they faithfully represent the original.

We deny that any essential element of the Christian faith is affected by the absence of the autographs. We further deny that this absence renders the assertion of biblical inerrancy invalid or irrelevant.[3]

Thus, any discrepancies in the manuscripts simply cannot touch the doctrine of inerrancy. But what of the discrepancies? What kind of variances are there? Are they so great that they conceal the wording of the original from view? Hardly. The fact is that the vast, vast majority of these discrepancies are matters of spelling or obscurity.

This certainly takes a good deal of steam out of the bluster of the critics. Theologian Wayne Grudem has summarized the differences in the manuscripts like this:

…for over 99 percent of the words of the Bible, we know what the original manuscript said. Even for many of the verses where there are textual variants (that is, different words in different ancient copies of the same verse), the correct decision is often quite clear, and there are really very few places where the textual variant is both difficult to evaluate and significant in determining the meaning. In the small percentage of cases where there is significant uncertainty about what the original text said, the general sense of the sentence is usually quite clear form the context.[4]

More significant is the conclusion of Bart Ehrman concerning these differences. His conclusions are significant because Ehrman is a former evangelical turned atheist New Testament scholar. He is the current media darling on these matters and has made quite a comfortable living attempting to debunk and cast doubt on the New Testament in particular. To be clear, he feels that there are a few places where the discrepancies really do matter, but in his book, Misquoting Jesus, Ehrman, in answering a question posed to him by the editors, likewise admitted that the presence of discrepancies is not simply shattering to Christianity and that the vast majority of them simply do not matter.

Why do you believe these core tenets of Christian orthodoxy to be in jeopardy based on scribal errors you discovered in the biblical manuscripts?

Essential Christian beliefs are not affected by textual variants in the manuscript tradition of the New Testament.[5]

Furthermore, last year, in a June 19, 2014, blog post entitle, “Who Cares?? Do the Variants in the Manuscripts Matter for Anything?” Ehrman spoke further to this when he said the following:

“[T]he vast majority of the…differences are immaterial, insignificant, and trivial…Probably the majority matter only in showing that Christian scribes centuries ago could spell no better than my students can today…[N]one of the variants that we have ultimately would make any Christian in the history of the universe come to think something opposite of what they already think about whatever doctrines are usually considered ‘major.’”[6]

Church, given the staggering amount of manuscript evidence over the first fifteen hundred years of the Christian era, we would expect human errors in the copies. What is truly wonderful, however, is that the insignificant and truly petty nature of over 99% of these discrepancies in no way affect our understanding of what the original manuscript said. You may therefore hold your Bible with confidence, especially in the face of uniformed challenges to its reliability from those who, on the basis of a surface reading and understanding of the data, think they have found an irrefutable silver bullet against the faith.

Jesus and the Apostles viewed the Bible as reliable and God-given and quoted from it extensively.

Above all of these reasons, however, is one that is more significant than all others. We can get at this reason by listening closely to what Jesus said in His wilderness temptations in Matthew 4.

1 Then Jesus was led up by the Spirit into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil. 2 And after fasting forty days and forty nights, he was hungry. 3 And the tempter came and said to him, “If you are the Son of God, command these stones to become loaves of bread.” 4 But he answered, “It is written, “‘Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of God.’” 5 Then the devil took him to the holy city and set him on the pinnacle of the temple 6 and said to him, “If you are the Son of God, throw yourself down, for it is written, “‘He will command his angels concerning you,’ and “‘On their hands they will bear you up, lest you strike your foot against a stone.’” 7 Jesus said to him, “Again it is written, ‘You shall not put the Lord your God to the test.’” 8 Again, the devil took him to a very high mountain and showed him all the kingdoms of the world and their glory. 9 And he said to him, “All these I will give you, if you will fall down and worship me.” 10 Then Jesus said to him, “Be gone, Satan! For it is written, “‘You shall worship the Lord your God and him only shall you serve.’” 11 Then the devil left him, and behold, angels came and were ministering to him.

Do you notice how Jesus began all three of his responses to the devil?

4 It is written…

7 Again, it is written…

10 For it is written

“It is written.” Jesus appeals three times to the writings. What writings? The writings of scripture.

Jesus thought the Bible was reliable and authoritative. He agreed that the scriptures are theopneustos, God-breathed.

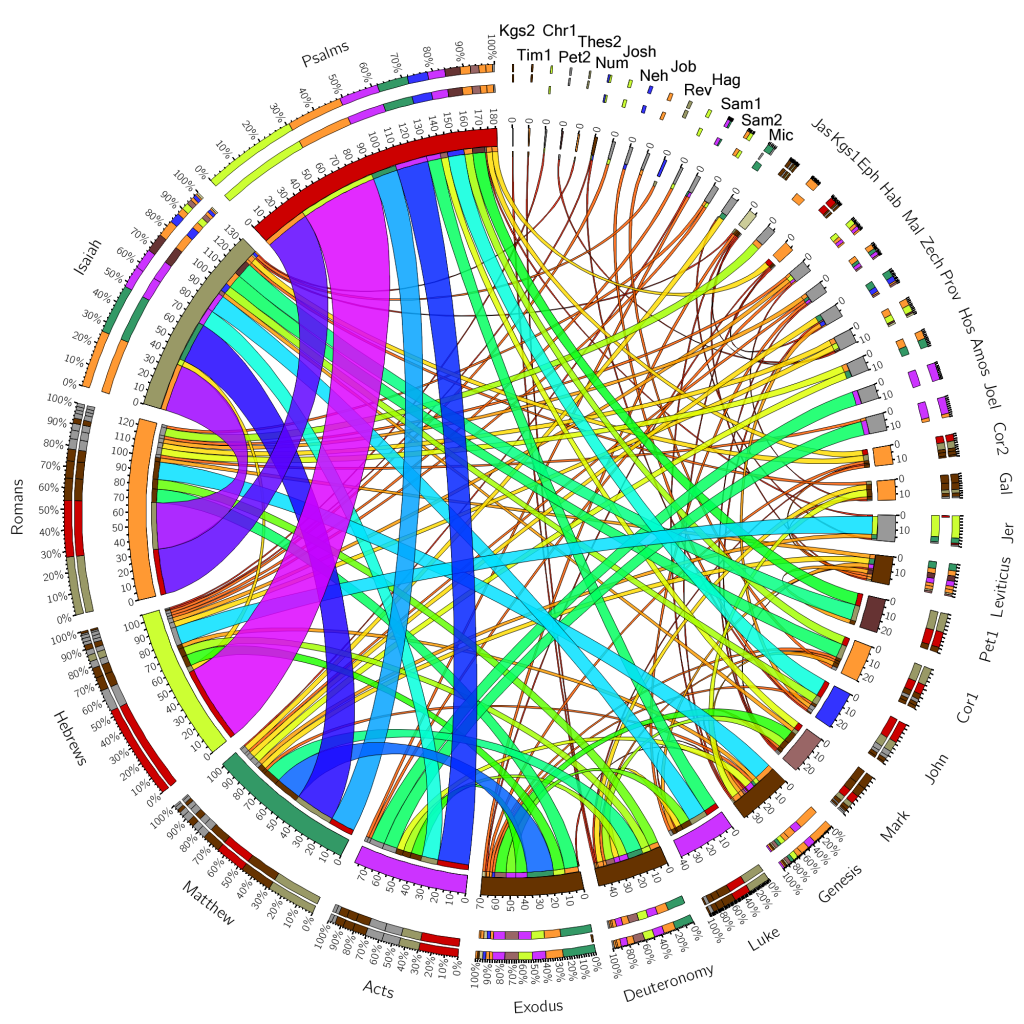

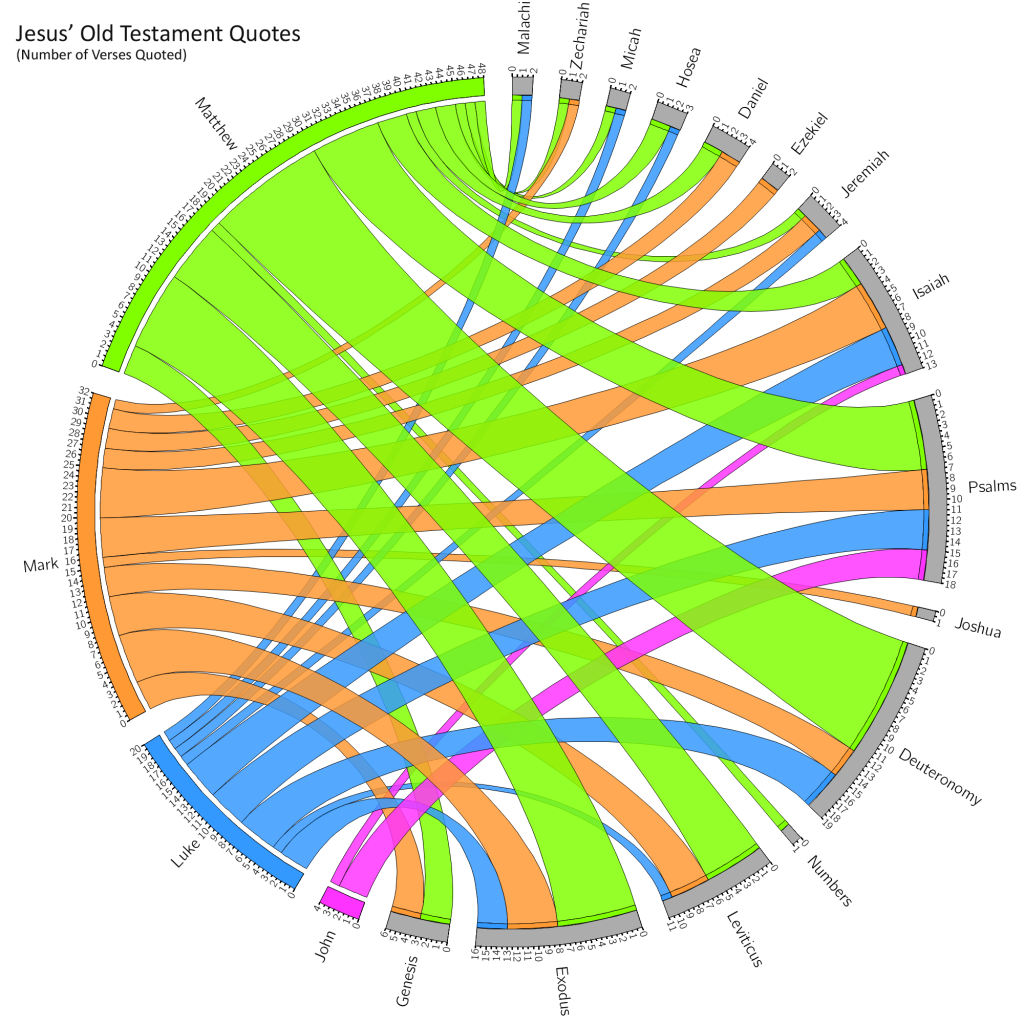

This is the evidence above all other evidence, the proof above all proof: Jesus, the Son of God, quoted and relied upon scripture. Furthermore, so did the apostles. In fact, the New Testament is filled with references to the Old Testament. Here, for instance, is a chart showing every place in which the New Testament quotes the Old Testament, in which any portion of scripture references any other portion:

And here is another showing how often Jesus quoted the Old Testament:

The evidence is undeniable: Jesus and His apostles felt that the scriptures were authoritative and reliable. In his essay, “New Testament Use of the Old Testament,” Roger Nicole writes:

[A] very conservative count discloses unquestionably at least 295 separate references to the Old Testament [in the New Testament]. These occupy some 352 verses of the New Testament, or more than 4.4 per cent. Therefore one verse in 22.5 of the New Testament is a quotation.

If clear allusions are taken into consideration, the figures are much higher: C. H. Toy lists 613 such instances, Wilhelm Dittmar goes as high as 1640, while Eugen Huehn indicates 4105 passages reminiscent of Old Testament Scripture. It can therefore be asserted, without exaggeration, that more than 10 per cent of the New Testament text is made up of citations or direct allusions to the Old Testament. The recorded words of Jesus disclose a similar percentage. Certain books like Revelation, Hebrews, Romans are well nigh saturated with Old Testament forms of language, allusions and quotations…

If we limit ourselves to the specific quotations and direct allusions which form the basis of our previous reckoning, we shall note that 278 different Old Testament verses are cited in the New Testament: 94 from the Pentateuch, 99 from the Prophets, and 85 from the Writings. Out of the 22 books in the Hebrew reckoning of the Canon only six (Judges-Ruth, Song of Solomon, Ecclesiastes, Esther, Ezra-Nehemlah, Chronicles) are not explicitly referred to. The more extensive lists of Dittmar and Huehn show passages reminiscent of all Old Testament books without exception.

Nicole then says this about the New Testament use of the Old Testament.

The New Testament writers used quotations in their sermons, in their histories, in their letters, in their prayers. They used them when addressing Jews or Gentiles, churches or individuals, friends or antagonists, new converts or seasoned Christians. They used them for argumentation, for illustration, for instruction, for documentation, for prophecy, for reproof. They used them in times of stress and in hours of mature thinking, in liberty and in prison, at home and abroad. Everywhere and always they were ready to refer to the impregnable authority of Scripture.

Jesus Christ…quoted the Old Testament in support of his teaching to the crowds; he quoted it in his discussions with antagonistic Jews; he quoted it in answer to questions both captious and sincere; he quoted it in instructing the disciples who would have readily accepted his teaching on his own authority; he referred to it in his prayers, when alone in the presence of the Father; he quoted it on the cross, when his sufferings could easily have drawn his attention elsewhere; he quoted it in his resurrection glory, when any limitation, real or alleged, of the days of his flesh was clearly superseded. Whatever may be the differences between the pictures of Jesus drawn by the four Gospels, they certainly agree in their representation of our Lord’s attitude toward the Old Testament: one of constant use and of unquestioning endorsement of its authority.[7]

The Bible is authoritative and reliable and trustworthy. It is God’s word to us. It is the Bible that Jesus quoted and pointed to time and again. It is the Bible that the apostles quoted in advancing the gospel in the world. It is the Bible that the early church fathers pointed to and quoted and alluded to time and time and time again. It is the Bible that the followers of Jesus wrote then copied over and over and over and over again. It is the Bible that was spread and sent and carried throughout the world. It is the Bible that followers of Jesus have labored to copy and preserve and whose value many of them have demonstrated and confirmed with their own blood. It is the Bible that this Church preaches and on which we stand.

It is God’s word to humanity. It points us to Jesus, the Word who was with God and who is God. It is the infallible, inerrant, trustworthy, reliant word, the scriptures that still reveal the power of the gospel and teach us divine truth and draw our eyes to Jesus.

[1] (2013-07-01). In Defense of the Bible: A Comprehensive Apologetic for the Authority of Scripture (Kindle Locations 3210-3219). B&H Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

[2] Quoted in F.F. Bruce, The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable? (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1995), p.20.

[3] Carl F.H. Henry. “The God Who Speaks and Shows: Fifteen Theses, Part Three.” God, Revelation, and Authority. Volume IV. (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 1999), p.213.

[4] Wayne Grudem, Systematic Theology. (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1994), p.96.

[5] Referenced by Dan Wallace at the 50.20 mark in his 2013 Ouachita Baptist University lecture, “How Much Did the Scribes Corrupt the New Testament?” https://vimeo.com/74471900

[6] https://ehrmanblog.org/who-cares-do-the-variants-in-the-manuscripts-matter-for-anything/

[7] https://www.bible-researcher.com/nicole.html