1 “Now these are the rules that you shall set before them. 2 When you buy a Hebrew slave, he shall serve six years, and in the seventh he shall go out free, for nothing. 3 If he comes in single, he shall go out single; if he comes in married, then his wife shall go out with him. 4 If his master gives him a wife and she bears him sons or daughters, the wife and her children shall be her master’s, and he shall go out alone. 5 But if the slave plainly says, ‘I love my master, my wife, and my children; I will not go out free,’ 6 then his master shall bring him to God, and he shall bring him to the door or the doorpost. And his master shall bore his ear through with an awl, and he shall be his slave forever. 7 “When a man sells his daughter as a slave, she shall not go out as the male slaves do. 8 If she does not please her master, who has designated her for himself, then he shall let her be redeemed. He shall have no right to sell her to a foreign people, since he has broken faith with her. 9 If he designates her for his son, he shall deal with her as with a daughter. 10 If he takes another wife to himself, he shall not diminish her food, her clothing, or her marital rights. 11 And if he does not do these three things for her, she shall go out for nothing, without payment of money.

One of the interesting things about preaching through whole books of the Bible is that you cannot skip the hard parts. And that is a good thing. If we believe the Bible to be God’s Word and believe that all of it is profitable, that means we must be willing to wrestle with the parts we find difficult. Let us remember that while there are timeless principles in all of scripture, there are indeed parts that are culturally conditioned to the day in which it was written. In these parts, we do not simply lift, move to our day, and literally apply a given text because the cultural structures in which these kinds of texts made sense do not apply today. So what we do in these cases is make a distinction between the element that was literally applicable to that given culture and the element that is timeless and applies across all generations and locales.

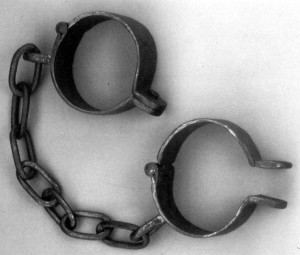

For instance, our text delineates rules concerning the institution of slavery. Obviously, we do not have slaves today and we would join with Christians the world over in seeing such an institution as unbecoming of the children of God. In truth, we would see it as a violation of the image of God in man. But here, and even at points in the New Testament, we find references to slavery that are not condemning the institution outright like we would like. So what are we to make of such texts? First, let us hear the passage:

1 “Now these are the rules that you shall set before them. 2 When you buy a Hebrew slave, he shall serve six years, and in the seventh he shall go out free, for nothing. 3 If he comes in single, he shall go out single; if he comes in married, then his wife shall go out with him. 4 If his master gives him a wife and she bears him sons or daughters, the wife and her children shall be her master’s, and he shall go out alone. 5 But if the slave plainly says, ‘I love my master, my wife, and my children; I will not go out free,’ 6 then his master shall bring him to God, and he shall bring him to the door or the doorpost. And his master shall bore his ear through with an awl, and he shall be his slave forever. 7 “When a man sells his daughter as a slave, she shall not go out as the male slaves do. 8 If she does not please her master, who has designated her for himself, then he shall let her be redeemed. He shall have no right to sell her to a foreign people, since he has broken faith with her. 9 If he designates her for his son, he shall deal with her as with a daughter. 10 If he takes another wife to himself, he shall not diminish her food, her clothing, or her marital rights. 11 And if he does not do these three things for her, she shall go out for nothing, without payment of money.

Our text is drawing a distinction between the handling of male slaves and the handling of female slaves, or, as many suggest, the handling of concubines. Let us consider what this means.

It seems clear that, for whatever reason, the Lord regulated certain undesirable realities in the Old Testament in light of the hardness of the Israelite’s hearts without advocating those realities He regulated.

I would like to begin by pointing out that, regardless of how one understands this, it seems clear that the Lord sometimes regulated certain undesirable realities in the Old Testament in light of the hardness of the Israelite’s hearts without advocating the realities He regulated. What do this mean? It means that the Lord allowed certain things to happen, and put guidelines around these things, that were neither ideal nor good but were part of the culture of the day.

This is difficult to understand, and we must be careful with such an idea, but I will note that Jesus appear to acknowledge this phenomenon in Matthew 19.

3 And Pharisees came up to him and tested him by asking, “Is it lawful to divorce one’s wife for any cause?” 4 He answered, “Have you not read that he who created them from the beginning made them male and female, 5 and said, ‘Therefore a man shall leave his father and his mother and hold fast to his wife, and the two shall become one flesh’? 6 So they are no longer two but one flesh. What therefore God has joined together, let not man separate.” 7 They said to him, “Why then did Moses command one to give a certificate of divorce and to send her away?” 8 He said to them, “Because of your hardness of heart Moses allowed you to divorce your wives, but from the beginning it was not so. 9 And I say to you: whoever divorces his wife, except for sexual immorality, and marries another, commits adultery.”

Again, the implications of this need to be thought through, but the point seems to be firmly established: it seems clear that, for whatever reason, the Lord regulated certain undesirable realities in the Old Testament in light of the hardness of the Israelite’s hearts without advocating those realities He regulated.

While the Old Testament does not offer a denunciation of slavery, it is quite possible that it is discouraging it even in the regulations it offers for it.

What is more, the presence of regulations do not necessarily equate to approval of that which is being regulated if, in fact, the structure of the regulations build in an element of shame for those who indulge in such. This is a bit of a nuance on the first point, and it is an intriguing argument. Old Testament scholar Victor Hamilton has made this argument and it is worthy of consideration.

Before turning to Exod. 21: 1– 11, let me state my own position. I reject the view that the Bible gives its imprimatur to slavery and looks the other way when ethical concerns raise their heads. Nor do I accept the view that the Bible endorses but tries to modify and ameliorate the practice of slavery. There are other things that the pagan nations did and the OT absolutely prohibits, like having idols, or cutting oneself, or eating pork, or working on Saturdays. The OT never tries to modify them. It exorcises them.

I believe the OT attempts, through its slave laws, to dissuade Israelites from the practice of slavery. I say this for two reasons. First, the most interesting slave law of all in the Bible is Deut. 23:15–16: “If a slave has taken refuge with you, do not hand him over to his master. Let him live among you wherever he likes and in whatever town he chooses” (and possibly the OT background to Paul’s Letter to Philemon). That is to say, a slave can choose not to be a slave. To gain his freedom, he need not wait those six years. He can simply and legally run away, without consequence to either the fugitive or to the one who is harboring him. Here is one major difference between the codes. In the Laws of Eshnunna (laws 12– 13) is a stiff fine for harboring a runaway slave, and Hammurabi’s Code (numbers 15– 16) makes it a capital offense. As Clines (1995a: 78, 81) has pointed out, “If a slave can choose not to be a slave, the concept of slavery does not exist as it once was thought to exist. . . . Slavery is in a sense abolished when it ceases to be a state that a person is forced into against their will.”

Here is the second reason why I believe the OT tries to dissuade the practice of slavery (and I reference here to Sternberg [1998: 483– 93] as the source of some of my thoughts). Exodus 21: 2 begins with “When you buy [qānâ] a Hebrew slave [ʿebedʿibrî ]. . . .” These expressions appear in Genesis in conjunction with Joseph’s slavery in Egypt. His brothers sell (mākar) him to some caravaners heading to Egypt (Gen. 37: 28). Potiphar buys [qānâ] him from them (Gen. 39: 1), and Potiphar’s wife sneeringly refers to Joseph as “that Hebrew slave” (hāʿebed hāʿibrî) in Gen. 39: 17. If Exod. 21: 2 would say, “When you acquire/ buy an Israelite slave,” the parallel of the Exodus slave law with Joseph would be nonexistent. As it now stands, the slave law of Exod. 21 appears to hold out Potiphar and Mrs. Potiphar as the model of somebody who has “bought” a “Hebrew slave,” resulting in all the tragic misfortunes that befall this Hebrew slave (years of imprisonment, character assassination, to name a few). As Sternberg (1998: 486) says, “The tacit Josephic precedent triggers its own, story-length prolepsis in the Mosaic audience’s mind, with a view to deterring them from reenacting this follow-up in the world.”

Another parallel with Genesis language is this. One may assume that a major reason why a person would voluntarily become a slave, or sell one’s daughter into slavery, is because of staggering debt and poverty from which one cannot extricate oneself. The Egyptian people, because of their famine-ravaged land, say to Joseph, now their Egyptian prime minister, “Buy [qānâ] us.” So Joseph “bought [qānâ] all the land of Egypt. . . . I have bought [qanah] you and your land” (Gen. 47: 19, 20, 23), in return for which the people promised (Gen. 47: 25) to be “slaves” (ʿăbādîm) to Pharaoh (NIV, “in bondage to Pharaoh”). Joseph, the one “bought,” has become Joseph the “buyer.” Joseph, once the ʿebed, “slave,” has become the ʾādôn, “master.” The enslaved has become the enslaver.

The Israelites now are only about three months out of Egypt. On three earlier occasions during those three months, slavery back in Egypt is their preferred option (Exod. 14: 10– 12; 16: 2– 3; 17: 1– 3), and here is the Lord speaking to his people about enslaving a Hebrew brother. In its own way Exod. 21: 5’ s “I love my master” is a later form of an earlier “I love my Egypt (and all the security and comforts it provides).” In a review of Sternberg’s book, Cohn (2001: 740) catches the drift of the argument: “The texts aim to stigmatize an Israelite who would enslave another by coding him in the role of a Hamite [Egyptian] master, as well as tarring an Israelite who would choose servitude over liberty by coding him as a throwback to Egyptian slavery.”[1]

Thus, the surprising allowances for the liberation of escaped slaves as well as the evocation of very recent memories of the Jews’ own enslavement in Egypt introduces an element of shame into the very institution. It is a subtle point, and perhaps one that we wish would be much more explicit, but it does hold relative significance.

Ultimately, the gospel of Christ would lay the foundation for abolitionism.

For followers of Christ, of course, all that God commands finds its ultimate fulfillment in Jesus Christ. It is profoundly important to notice that the gospel Christ preached did in fact lay the foundation for the eventual abolition of the slave trade. To be sure, it is historically disingenuous to suggest that the Church did not traffic in the slave trade in ways that are truly shameful. Large numbers of Christians did do so, and it is a tragedy of the first order. Even so, we find within the gospel the seeds that eventually grew into the undermining of slavery. Those seeds are sown in the life and teachings and saving work of Christ and begin to bear fruit even in the apostolic age. Thus, Paul could proclaim in Galatians 3:28:

27 For as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ. 28 There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. 29 And if you are Christ’s, then you are Abraham’s offspring, heirs according to promise.

That is a radical pronouncement: “there is neither slave nor free…for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” Here we begin to see the theological ammunition that would be used to undermine the very foundations of slavery. Even and especially in Philemon, a book in which Paul is returning a run away slave to his Christian master, we find principles that, if followed in the ancient world, would have utterly revolutionized and ultimately destroyed slavery as an social institution. Consider Philemon 10-22 and the ways in which Paul strikes at the very notion of slavery.

10 I appeal to you for my child, Onesimus, whose father I became in my imprisonment. 11 (Formerly he was useless to you, but now he is indeed useful to you and to me.) 12 I am sending him back to you, sending my very heart. 13 I would have been glad to keep him with me, in order that he might serve me on your behalf during my imprisonment for the gospel, 14 but I preferred to do nothing without your consent in order that your goodness might not be by compulsion but of your own accord. 15 For this perhaps is why he was parted from you for a while, that you might have him back forever, 16 no longer as a bondservant but more than a bondservant, as a beloved brother—especially to me, but how much more to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord. 17 So if you consider me your partner, receive him as you would receive me. 18 If he has wronged you at all, or owes you anything, charge that to my account. 19 I, Paul, write this with my own hand: I will repay it—to say nothing of your owing me even your own self. 20 Yes, brother, I want some benefit from you in the Lord. Refresh my heart in Christ. 21 Confident of your obedience, I write to you, knowing that you will do even more than I say. 22 At the same time, prepare a guest room for me, for I am hoping that through your prayers I will be graciously given to you. [bold, mine]

Let us ask ourselves a simple question: if slave owners in the ancient world treated slaves as their brothers who were no longer slaves with whom they would spend eternity who were useful to them in the Lord, would it not have obliterated slavery in the ancient world? This is why we begin to see Christianity striking blows at the edifice of slavery in the ancient and, later, in the modern world.

In the fourth century, Gregory of Nyssa denounced the institution of slavery as wicked. David Bentley Hart points out that the entire ancient world does not contain a denunciation as fierce as Gregory’s.

Nowhere in the literary remains of antiquity is there another document quite comparable to Gregory of Nyssa’s fourth homily on the book of Ecclesiastes: certainly no other ancient text still known to us—Christian, Jewish, or Pagan—contains so fierce, unequivocal, and indignant a condemnation of the institution of slavery.[2]

In his book, The Path of Celtic Prayer, Calvin Miller pointed that, in the fifth century, St. Patrick of Ireland “was, for example, always speaking against the slave trade and unkind and cruel leaders (see his Letter to Coroticus).”[3]

In William Carey’s 1792 missionary manifesto, An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens, he remarked that “a noble effort has been made to abolish the inhuman Slave-Trade, and though at present it has not been so successful as might be wished, yet it is to be hoped it will be persevered in, till it is accomplished.”[4]

And of course we must not forget that noble follower of Jesus, William Wilberforce, who fought so valiantly to abolish the British slave trade.

As I said earlier, we rightly wish that these examples were much more numerous and intense, but it should be noted that the earliest voices and many of the most noble voices for the abolition of slavery were the voices of those who had bowed before the Lordship of Christ and embraced the truth of the gospel. That is no small thing.

What, then, of the regulations concerning slavery in Exodus? They are concessions, the reasons for which we cannot ultimately know, that were intended to establish guidelines around a social institution that was widely embraced in the ancient world, that certainly was not and is not part of God’s ideal for His people, but which was allowed for reasons that reside in the mysteries of God’s will. They spoke to an institution that was a regrettable part of the ancient world, and is, we note with sadness, still a regrettable part of too much of the world today, but an institution the foundations of which were eroded and then finally demolished by the liberating power of the gospel of Christ…for which we say, Amen!

The gospel of Christ sets free the slaves, then and now. As ever, the greatest slavery as the slavery of the fallen human heart. It is our slavery to our own passions and our own egos and our own fallen minds. And Christ Jesus comes to all of us slaves and throws open the door through the power of His life, death, and resurrection, and bids us emerge as free men and women.

[1] Hamilton, Victor P. (2011-11-01). Exodus: An Exegetical Commentary (Kindle Locations 12079-12116). Baker Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

[2] D. Bentley Hart, “The `Whole Humanity’: Gregory of Nyssa’s Critique of Slavery in Light of His Eschatology,” Scottish Journal of Theology, 54:1 (February 2001): 51. See also “Gregory of Nyssa and the Culture of Oppression.” https://www.baylor.edu/content/services/document.php/110976.pdf

[3] Calvin Miller, The Path of Celtic Prayer: An Ancient Way to Everyday Joy (Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP Books, 2007), p.138.

[4] William Carey, An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens. Kindle Edition. (530-531)

Pingback: Exodus | Walking Together Ministries