Job 17

Job 17

1 “My spirit is broken; my days are extinct; the graveyard is ready for me. 2 Surely there are mockers about me, and my eye dwells on their provocation. 3 “Lay down a pledge for me with you; who is there who will put up security for me? 4 Since you have closed their hearts to understanding, therefore you will not let them triumph. 5 He who informs against his friends to get a share of their property—the eyes of his children will fail. 6 “He has made me a byword of the peoples, and I am one before whom men spit. 7 My eye has grown dim from vexation, and all my members are like a shadow. 8 The upright are appalled at this, and the innocent stirs himself up against the godless. 9 Yet the righteous holds to his way, and he who has clean hands grows stronger and stronger. 10 But you, come on again, all of you, and I shall not find a wise man among you. 11 My days are past; my plans are broken off, the desires of my heart. 12 They make night into day: ‘The light,’ they say, ‘is near to the darkness.’ 13 If I hope for Sheol as my house, if I make my bed in darkness, 14 if I say to the pit, ‘You are my father,’ and to the worm, ‘My mother,’ or ‘My sister,’ 15 where then is my hope? Who will see my hope? 16 Will it go down to the bars of Sheol? Shall we descend together into the dust?”

In his bestselling book, Healing for Damaged Emotions, the late David Seamands wrote this about depression:

The most concise definition of depression I know is this: “Depression is frozen rage.” If you have a consistently serious problem with depression, you have not resolved some area of anger in your life. As surely as the night follows the day, depression follows unresolved, repressed, or improperly expressed anger.[1]

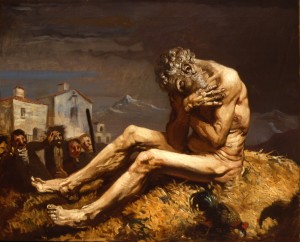

“Depression is frozen rage.” That is a very helpful definition to keep in mind as we consider Job’s next speech. At this point there seems no doubt that Job is dealing with serious depression and also that a strong aspect of that depression is, in fact, bound up with rage: rage at his unhelpful friends and rage at God Himself. And it had become frozen rage, a hard, deep-frozen knot of pain and confusion and resentment and bitterness that was ever working itself out of Job in words of disappointment and great grief.

This is what frozen rage looks like. Consider the cautionary tale of Job’s despair.

Job alternates between bemoaning his unhelpful friends, calling on God to vindicate him, and bemoaning God’s treatment of him.

Earlier in my ministry, I had an unpleasant meeting with a person whose spouse we had to confront concerning behavior he/she was involved in that was inappropriate and unbecoming of a Christian. The person we were meeting with was angry that we had confronted his/her spouse though we tried to explain that we had tried to do so redemptively, carefully, and biblically. I recall that meeting with a sense of pity, for the dear person through tears would alternately lash out at us for confronting his/her spouse then defend his/her spouse then lash out at the spouse that he/she had just defended a breath before. I recall feeling a sense of heartbreak for this person as he/she was obviously so hurt that he/she did not know where to assign blame. There is something of that happening with Job in Job 17. Like a wounded animal, Job lashed out at any and all.

1 “My spirit is broken; my days are extinct; the graveyard is ready for me. 2 Surely there are mockers about me, and my eye dwells on their provocation. 3 “Lay down a pledge for me with you; who is there who will put up security for me? 4 Since you have closed their hearts to understanding, therefore you will not let them triumph.

Job begins by returning once again to the idea of death. Specifically, Job sees himself as a man who is dead already in every way save his body. His “spirit is broken.” Something deep and profound within Job was beyond repair, he seems to say. The only thing he had to look forward to was death: “the graveyard is ready for me.”

Next, Job interestingly asks God to “lay down a pledge” for him and to “put up security” for him. Robert Alden has offered a helpful explanation of these enigmatic words.

The interpretation of this verse is dependent on the understanding of two cultural practices, not too different from our own. “Pledge” in the first line refers to some proof necessary to back up words. No testimony other than God’s would do to persuade Job’s friends that he was sinless.

The idiom of the second line is literally, “Who will strike hands?” that is, agree with a handshake to vouch for Job. Both verbs occur in Prov 6:1, a passage warning against cosigning notes. Job could find no one to endorse his innocence and by this question in v.3b did not expect to find anyone other than God (cf. 16:19).[2]

What is interesting about this is that Job still holds fast to his innocence (which is something he has done in every one of his speeches) and Job also realizes that God could vindicate him if God wanted. Alden sees in verse 4 Job’s belief that “it was God’s fault” since God had closed the eyes of his friends to the truth, but this seems to miss Job’s further point that God will not allow his friends to triumph. It should be noted, however, that there is great debate concerning how the final line of verse 4 should be translated. Regardless, Job does still see God as transcendent and powerful and able to vindicate him, even as Job is clearly angry at God. Thus, like the person I mentioned earlier, Job lashes out in anger in all directions, but not always in a consistent manner.

He continues his complaint in verses 5 and 6 by condemning God and his friends alike.

5 He who informs against his friends to get a share of their property—the eyes of his children will fail. 6 “He has made me a byword of the peoples, and I am one before whom men spit. 7 My eye has grown dim from vexation, and all my members are like a shadow. 8 The upright are appalled at this, and the innocent stirs himself up against the godless.

Job curses his friends and their children by suggesting that they have selfish motives for condemning him. He then announces that God has reduced Him to a loathsome thing: “I am one before whom men spit.” Job sees himself as contemptible in the eyes of all who see him, a cursed object of derision and scorn. Such is the weight of Job’s curse that he feels himself slipping from the land of the living and into the realm of shadow and darkness.

Next, Job makes another proclamation of his own innocence and, surprisingly, possibly even of his own future victory.

9 Yet the righteous holds to his way, and he who has clean hands grows stronger and stronger. 10 But you, come on again, all of you, and I shall not find a wise man among you. 11 My days are past; my plans are broken off, the desires of my heart. 12 They make night into day: ‘The light,’ they say, ‘is near to the darkness.’

Verse 9 sits oddly within the surrounding verses. As has happened before, a faint light breaks through the darkness of Job’s anger and dismay. He pronounces himself as “righteous” once again and notes that “he who has clean hands grows stronger and stronger.” Does this mean that Job has some small hope of future vindication and vindication. Concerning Job’s expression of innocence in verse 9, Delitzsch said, “These words of Job are like a rocket which shoots above the tragic darkness of the book, lighting it up suddenly, although only for a short time.”[3]

One is tempted to say that there is almost a schizophrenic quality about Job’s words. They seem almost to emanate from two distinct personages. But that would be a cruel thing to say. Job’s malady is not madness. Rather, it is crippling loss and grief and pain. He is speaking not like a man who has lost his mind but rather like a man whose heart has been shattered. Thus, Job can condemn his friends, recognize God’s power to vindicate, rage against God, proclaim himself dying and defeated, and announce that the innocent grow stronger and stronger all at the same time before returning to the idea that he is defeated, crushed, and done for.

Grief and pain have an amazing capacity to cloud the mind and distort the speech. This is evident in Job’s vacillations. The vacillating nature of Job’s words should perhaps lead us to be careful and cautious in how we respond to people who are deeply hurting. We should see in Job the results of mental, spiritual, and physical agony, namely, the loss of rigid consistency and linear lucidity in thought. Hurting people are often “all over the map,” we might say, and so might we be in a similar situation.

This reality can finally be seen in the concluding words of Job 17.

While Job appears hopeless, hope is still in his vocabulary.

Job next begins speaking of “his hope.”

13 If I hope for Sheol as my house, if I make my bed in darkness, 14 if I say to the pit, ‘You are my father,’ and to the worm, ‘My mother,’ or ‘My sister,’ 15 where then is my hope? Who will see my hope? 16 Will it go down to the bars of Sheol? Shall we descend together into the dust?”

Interpreting this section can be a challenge. Tremper Longman, for instance, sees Job’s hope as his own death. He is hoping for death. Thus, in Longman’s view, his reference to hope is truly not hope at all. John Hartley, however, sees Job’s reference to hope as referring to “his vindication that would eventuate in the restoration of his honor and his health,” but recognizes that Job sees this hope as impossible since his death is imminent and certain. “Since hope is synonymous with life,” writes Hartley, “it could have no existence in death. Therefore, the dust will be the end for both his hope and himself.” In Hartley’s view, Job’s death destroys his hope.[4] I am inclined to agree with Harley in this. Job is speaking of hope in terms of future vindication but he does realize that this is a fleeting fancy in the face of his immanent death.

The famed Greek author Nikos Kazantzakis died of leukemia in 1957. His tombstone read, “I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I am free.”[5] In contrast, Job wanted to hope but could not. His lack of hope was not a liberation, and, in truth, it should be said, neither was Kazantzakis’. Job’s lack of hope did not comfort him. He wanted hope but realized that he had to abandon it in death. Death divorced Job from his hope and, in so doing, it divorced him from peace of mind.

It is an interesting thing to observe, this conviction that the coming of death means the departure of hope. Undoubtedly many feel this way today. As followers of Jesus, however, we can never view it in these terms, for if Christ came to do anything at all He came to remove the sting of death so that hope could flourish in the face of it and beyond it. If the resurrection of Jesus tells us anything, it is that death does not defeat hope. Paul put this beautifully in 1 Corinthians 15.

12 Now if Christ is proclaimed as raised from the dead, how can some of you say that there is no resurrection of the dead? 13 But if there is no resurrection of the dead, then not even Christ has been raised. 14 And if Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is in vain and your faith is in vain. 15 We are even found to be misrepresenting God, because we testified about God that he raised Christ, whom he did not raise if it is true that the dead are not raised. 16 For if the dead are not raised, not even Christ has been raised. 17 And if Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins. 18 Then those also who have fallen asleep in Christ have perished. 19 If in Christ we have hope in this life only, we are of all people most to be pitied. 20 But in fact Christ has been raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep.

Easter means that hope goes beyond the grave. Death does not defeat hope for Christ has defeated death. The resurrected Christ is therefore “the firstfruits,” meaning the first of the many who will arise with Him. All who are in Christ have hope beyond the grave!

Yet again, we wish we could preach the gospel to Job…but we know that now we have no need, for Job now stands in the presence of the risen Christ. Job now knows what we on this side of the cross know: that hope does indeed follow us if we are God’s people, that hope does not have stop at our funerals, that there is life and life eternal beyond the grave.

If depression is frozen rage, surely the warm glow of the grace of God and the hope of the gospel can melt it into non-existence. Surely the fire of the Spirit of God that indwells all who have come to Christ in hope and repentance can banish the ice of rage, disappointment, and pain. In so doing, the Holy Spirit makes room for love, for peace, for joy, for contentment, and for hope.

Such is the power of the risen Lamb.

[1] Seamands, David A. (2010-11-01). Healing for Damaged Emotions (Kindle Locations 2061-2063). David C Cook. Kindle Edition.

[2] Robert A. Alden, Job. The New American Commentary. Vol. 11 (Nashville, TN: Broadman & Holman Publishing Group, 1993), p.189.

[3] Quoted in Robert A. Alden, p.191.

[4] Tremper Longman III, Job. Baker Commentary on the Old Testament. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2012), p.243. John E. Hartley, The Book of Job. The New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Eds., R.K. Harrison and Robert L. Hubbard, Jr. (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1988), p.271.

[5] Kazantzakis, Nikos (2012-09-04). Saint Francis (Kindle Location 51). Simon & Schuster. Kindle Edition.

Pingback: Job | Walking Together Ministries