Job 25

Job 25

1 Then Bildad the Shuhite answered and said: 2 “Dominion and fear are with God; he makes peace in his high heaven. 3 Is there any number to his armies? Upon whom does his light not arise? 4 How then can man be in the right before God? How can he who is born of woman be pure? 5 Behold, even the moon is not bright, and the stars are not pure in his eyes; 6 how much less man, who is a maggot, and the son of man, who is a worm!”

Job 26

1 Then Job answered and said: 2 “How you have helped him who has no power! How you have saved the arm that has no strength! 3 How you have counseled him who has no wisdom, and plentifully declared sound knowledge! 4 With whose help have you uttered words, and whose breath has come out from you? 5 The dead tremble under the waters and their inhabitants. 6 Sheol is naked before God, and Abaddon has no covering. 7 He stretches out the north over the void and hangs the earth on nothing. 8 He binds up the waters in his thick clouds, and the cloud is not split open under them. 9 He covers the face of the full moon and spreads over it his cloud. 10 He has inscribed a circle on the face of the waters at the boundary between light and darkness. 11 The pillars of heaven tremble and are astounded at his rebuke. 12 By his power he stilled the sea; by his understanding he shattered Rahab. 13 By his wind the heavens were made fair; his hand pierced the fleeing serpent. 14 Behold, these are but the outskirts of his ways, and how small a whisper do we hear of him! But the thunder of his power who can understand?”

Erasmus of Rotterdam is still recognized as one of the truly great minds ever to appear on the earth. A prodigious scholar, Erasmus took a degree in theology, though theology was but one of his many pursuits. Furthermore, he was not overly thrilled with taking a degree in theology and claims that he did so only because his friends pushed him in to it.

Erasmus’ main objection to the theology of his day was that too many people pushed too far into the divine mysteries when they should, at points, have simply put their hands over their mouths in honor of the impenetrable glories of God.

Of course, Christianity is a religion of revelation, so not all of His glories are unintelligible to us. His greatest glory – His Son – came to reveal Himself and the Father to us. Even then, though, there are impenetrable mysteries into which we will never be able to fully go on this side of heaven.

Erasmus saw a lot of undue speculation in theology and, as such, he saw a lot of arrogance. Why, after all, do we have to force an opinion on every question about God? Here is how Erasmus put it:

There are sanctuaries in the sacred studies which God has not willed that we should probe, and if we try to penetrate there, we grope in ever deeper darkness the farther we proceed, so that we recognize, in this manner, too, the inscrutable majesty of divine wisdom and the imbecility of human understanding.[1]

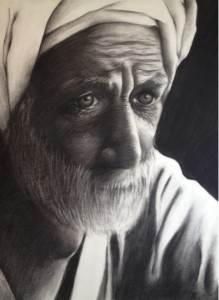

We have come to a point in the unfolding of Job’s story and his conversation with his friends where Erasmus’ words should be considered. In chapter 25, Bildad, seemingly frustrated and exhausted, forces yet one more word about God and man out of his mouth, though one cannot help but wonder if his heart was really in it. Job, in his response in chapter 26, rebukes him for his unhelpful foolishness and extols the awesome power and majesty of God that transcends our understanding and puny attempts to capture His mysteries in our own little minds.

Bildad attempts an end-around by arguing that, after all, everything and everybody is so utterly wretched that God is right to do whatever He does anyway.

There must be a place of silence in theology, and that place is the line past which we simply do not know. Remember that the entire book of Job will end with Job placing his hand over his mouth before the majesty of God: “Behold, I am of small account; what shall I answer you? I lay my hand on my mouth” (Job 40:4). One wishes that Bildad had done the same before speaking in Job 25.

Job 25

1 Then Bildad the Shuhite answered and said: 2 “Dominion and fear are with God; he makes peace in his high heaven. 3 Is there any number to his armies? Upon whom does his light not arise? 4 How then can man be in the right before God? How can he who is born of woman be pure? 5 Behold, even the moon is not bright, and the stars are not pure in his eyes; 6 how much less man, who is a maggot, and the son of man, who is a worm!”

Francis Andersen says of this chapter that “the discussion is nearly exhausted. The brevity of Bildad’s final speech and the absence of a third speech by Zophar are indications that the friends have run out of fuel.”[2] That is true, though running out of fuel does not, regrettably, always translate into running out of words. “One wishes, discreetly,” William F. Buckley, Jr., once wrote, “that, as one experiences one’s ignorance, pari passu [“side-by-side”] one would lower one’s voice.”[3] Regrettably, this does not happen too often.

In essence, Bildad, in this brief psalm, speaks of the might of God and the utter depravity of man. On the face of it, this is not wholly wrong, of course. God is indeed mighty! His armies are indeed great! And man is indeed impure and mired in sin.

Yet one senses an unhealthy motivation behind Bildad’s words. One senses, first of all, that Bildad is simply trying to win an argument here. Theology done for anything other than the search for truth and for the furtherance of God’s glory on the earth becomes an ignoble thing. One should not slap bumper-sticker theology on vain and narcissistic efforts to bolster one’s own ego.

What is more, Bildad seems to be attempting to shut Job up by pointing to the distance between a holy God and sinful man. Again, God is holy and man is sinful. Yet it does appear that Bildad is appealing to these truths in an effort to tell Job to be quiet. He is ostensibly not applying the effects of this observation to himself. It is the strategic employment of theological truth for pugilistic reasons. Bildad’s declaration is a weapon here, not a proclamation.

That being said, there are also some problems with Bildad’s statement. “How much less man,” he says, “who is a maggot, and the son of man, who is a worm!” Again, dare not shrink from the painful reality of human depravity, yet this feels and sounds more Darwinian than biblical, does it not? What I mean is that Bildad’s denigration of man as a maggot and a worm almost seems to blaspheme by speaking against man as a unique creation bearing the image of God.

Man is sinful man…but he is a man! There is a point past which the doctrine of human depravity becomes dehumanizing. Man should not be deified, but he must be allowed to be human.

Now, is there a sense in which it is right to call man “a worm.” Properly understood, yes. John Piper, for instance, has spoken with some helpful words to this question in considering the great missionary William Carey’s tombstone inscription (an inscription he wrote himself): “A wretched, poor, and helpless worm, On Thy kind arms I fall.” Here is what Piper wrote:

I tweeted this morning that I would like to be “such a worm”. I said: “William Carey died today 1834. Epitaph: ‘A wretched poor and helpless worm, on thy kind arms I fall.’ O to be such a worm!”

Not everyone thinks it is biblically sound to call a new creature in Christ a worm, let alone to aspire to be one. It’s a good question.

First of all, my meaning: I want to be “such a worm”—a William-Carey-type worm. That is, an indomitable servant of Jesus, who, in spite of innumerable failures, perseveres productively to the end by grace alone through faith alone.

What was William Carey’s secret? How could he persevere for 40 years over all obstacles—as a homely man, suffering from recurrent fever, limping for years from an injury, and yet putting the entire Bible into six languages and parts of it into 29 other languages—what was the secret of this man’s usefulness for the kingdom?

It was the biblical combination of being “poor in spirit” (Matthew 5:3) and being strong in faith. The tweet was too short to include the last line of his epitaph. The whole thing reads:

WILLIAM CAREY

Born August 17the, 1761

Died June 9the, 1834

A wretched, poor, and helpless worm,

On Thy kind arms I fall.

The secret of his life was that as a “wretched, poor, helpless worm” he fell daily, and finally, into the arms of Jesus. When he did he “expected great things from God.” And therefore he “attempted great things for God.” He was a wonderfully fruitful worm.

I know he was a “saint” (Ephesians 1:1), a “new creation in Christ” (2 Corinthians 5:17), “precious in the sight of the Lord” (Psalm 116:15), “chosen” (Ephesians 1:4); a “royal priest” (1 Peter 2:9), “born of God” (1 John 5:1), “adopted” (Ephesians 1:5), “child of God” (1 John 3:1), “forgiven” (Ephesians 1:7); “justified” (Romans 5:1), “perfected” (Hebrews 10:14). I know that about myself too, and it is profoundly steadying and sweet.

But, my understanding of who I am until I die, also includes “wretched man that I am who will deliver me from this body of death” (Romans 7:24). It includes “blessed are the poor in spirit” (Matthew 5:3). It includes “a broken and contrite heart” that God will not despise (Psalm 51:17). It includes weeping bitterly over my sinfulness (Luke 22:62). It includes being “ashamed and confounded for my ways” (Ezekiel 36:32).

When God addresses the apple of his eye in Isaiah 41:14, he says,

Fear not, you worm Jacob, you men of Israel!

I am the one who helps you, declares the LORD.

God meant this to be humbling and encouraging. He meant it to produce broken-hearted boldness, contrite courage, lion-hearted lowliness.

William Carey was this kind of man. His worm-ness did not paralyze him. It empowered him, because it drove him daily into the arms of Jesus. So I say again, “O to be such a worm.”[4]

This is really quite helpful. If by “worm” we are referring to our utter dependence upon God or the vicious effects of sin on us, then it is appropriate. But Bildad calling man a maggot has an absurdist air about it. It presents us with a picture of man as worthless and beneath God’s very attention.

Surely we can communicate the sinfulness of man and the distance between man and God without diminishing the humanity of man? And surely we should not employ language that requires careful usage simply in order to make a hyperbolic power play an attempt to stymie further conversation.

The bigger issue, however, is the way in which Bildad attempts to claim God for his side even as he tries to highlight the distance between God in man. In reality, he is saying that God is distant from Job but not from him, for Bildad is still firmly convinced that God agrees with him.

In 1963, Bob Dylan’s song “With God on Our Side” appeared on his album “The Times They Are A-Changin’.” It quickly became a classic expression of the ways in which peoples claim that God agrees with them.

Oh my name it is nothin’

My age it means less

The country I come from

Is called the Midwest

I’s taught and brought up there

The laws to abide

And that the land that I live in

Has God on its side

Oh the history books tell it

They tell it so well

The cavalries charged

The Indians fell

The cavalries charged

The Indians died

Oh the country was young

With God on its side

Oh the Spanish-American

War had its day

And the Civil War too

Was soon laid away

And the names of the heroes

l’s made to memorize

With guns in their hands

And God on their side

Oh the First World War, boys

It closed out its fate

The reason for fighting

I never got straight

But I learned to accept it

Accept it with pride

For you don’t count the dead

When God’s on your side

When the Second World War

Came to an end

We forgave the Germans

And we were friends

Though they murdered six million

In the ovens they fried

The Germans now too

Have God on their side

I’ve learned to hate Russians

All through my whole life

If another war starts

It’s them we must fight

To hate them and fear them

To run and to hide

And accept it all bravely

With God on my side

But now we got weapons

Of the chemical dust

If fire them we’re forced to

Then fire them we must

One push of the button

And a shot the world wide

And you never ask questions

When God’s on your side

Through many dark hour

I’ve been thinkin’ about this

That Jesus Christ

Was betrayed by a kiss

But I can’t think for you

You’ll have to decide

Whether Judas Iscariot

Had God on his side

So now as I’m leavin’

I’m weary as —-

The confusion I’m feelin’

Ain’t no tongue can tell

The words fill my head

And fall to the floor

If God’s on our side

He’ll stop the next war

Dylan makes a great point: the indiscriminate and haughty assumption that God agrees with you on whatever it is you are doing really does lead to a kind of blind hard-headedness and inability to admit that you might be wrong. Oddly enough, Bildad is saying something very much like this to Job: “God is beyond us. We are maggots. That being said, God agrees with me and not with you.”

Job dismisses Bildad as unhelpful and then proclaims the goodness of God.

One of the greatest evidences that Bildad was not using the image of “worm” in the way that, say, William Carey used it, can be seen in Job’s sarcastic taunting of Bildad and then Job’s powerful proclamation of the glory of God.

Job 26

1 Then Job answered and said: 2 “How you have helped him who has no power! How you have saved the arm that has no strength! 3 How you have counseled him who has no wisdom, and plentifully declared sound knowledge! 4 With whose help have you uttered words, and whose breath has come out from you?

This drips with sarcasm! What a great help you are, Bildad! How very useful your words and attitude and approach have been! Could we hear the tone of these words as spoken and see Job’s mocking visage, we would realize that he was saying the exact opposite: Bildad was being absolutely unhelpful and, in fact, his words were not in harmony with divine truth (i.e., “whose breath has come out from you?”). It has been noted that Job, for the first time, uses the singular “you” repeatedly in these verses as opposed to the plural “you” he used before. There is, in other words, something cutting about his comments here. He has focused in on Bildad specifically with razor sharp precision. Something in Bildad’s little speech agitated Job greatly!

After rebuking Bildad, Job moves to a proper consideration of the majesty of God. I say “proper” because this should be seen as a corrective to Bildad’s proclamation.

5 The dead tremble under the waters and their inhabitants. 6 Sheol is naked before God, and Abaddon has no covering. 7 He stretches out the north over the void and hangs the earth on nothing. 8 He binds up the waters in his thick clouds, and the cloud is not split open under them. 9 He covers the face of the full moon and spreads over it his cloud. 10 He has inscribed a circle on the face of the waters at the boundary between light and darkness. 11 The pillars of heaven tremble and are astounded at his rebuke. 12 By his power he stilled the sea; by his understanding he shattered Rahab. 13 By his wind the heavens were made fair; his hand pierced the fleeing serpent. 14 Behold, these are but the outskirts of his ways, and how small a whisper do we hear of him! But the thunder of his power who can understand?”

Job makes a most powerful statement here, and he does so in order to tell Bildad something important: God’s glory is so great that Bildad cannot even begin to understand it. In order to make the point, Job marshalls a great deal of evidence. Interestingly, Old Testament scholars have pointed out that Job uses images from pagan mythology as well as the Bible in this speech. For instance:

- 5-6 (“the dead…Sheol is naked…Abaddon has no covering”) – John Walton observes, “The Akkadian myth The Descent of Ishtar to the Underworld recounts Ishtar’s passage through the seven gates of the netherworld. As each gate opens for her, Ishtar is required to forfeit another piece of her garments of splendor and power until at last she is left naked. Even so, Ereshkigal, the queen of the netherworld, trembles…at her presence.” Walton sees Job’s lumping of these elements together as “intriguing” but does point out that “the contexts are very different.”[5]

- 5 (“under the waters”) – parallels Genesis 1:7 (“And God made the expanse and separated the waters that were under the expanse from the waters that were above the expanse. And it was so.”)

- 7 (“the north”) – John Hartley observes of verses 5 and 6 that Job refers to “the realm of the dead…by three names, waters (mayim), Sheol, and Abaddon (‘abaddon).” Whereas “Sheol was thought to lie under the ocean and to be a murky, watery abode,” “the north” (v.7) “was the placed where the divine assembly gathered” in Ugaritic mythology and was therefore being used by Job here “symbolically, not geographically, for God’s habitation.”[6] There is a powerful statement here about the sole supremacy of God. The Lord God “stretches out the north over the void.” In other words, He is supreme over all other gods.

- 8 (“He binds up the waters in His thick clouds.”) – Walton wrote that “the imagery of cloud-enveloped waters likewise fits the ideas current in the ancient world.” This can be seen in the Enuma Elish, the Babylonian creation account. Furthermore, “An Assyrian artifact in the British Museum provides our only graphic representation of this phenomenon. It depicts the winged deity with drawn bow in the skies, flanked by bags containing hail or rain.”[7]

- 12-13 (“Rahab” and “the fleeing serpent”) – Hartley writes that “Rahab is the embodiment of all evil forces” and points out that “the creature nahas bariah, ‘the fleeing serpent’” appears not only in Isaiah 27:1 (“In that day the LORD with his hard and great and strong sword will punish Leviathan the fleeing serpent, Leviathan the twisting serpent, and he will slay the dragon that is in the sea.”) but also “in an Ugaritic text.” Likewise, it might also be paralleled with the dragon from Revelation 12:3.[8]

By drawing images from scripture as well as pagan theology, Job was saying that the God of Israel is the one true God and that He is Lord of the nations. Furthermore, His name and attributes ought not be employed to bolster a frustrated man’s temper tantrum. This passage is so very intriguing. It is almost as if Job sets aside his central argument just as Bildad has in order to rebuke Bildad for his careless use of the name of God. Bildad’s theology had become sloppy and emotive and manipulative. Job, in rebuking Bildad, reminded him of Whom he was speaking.

There is a lesson here for us. The Bible is not a collection of clobber verses to be strategically employed in your argument of the moment. It is not a holding tank for your own personal and pugilistic bumper stickers waiting for you to root around in until you find just the right maxim to shut up your opponent.

We are speaking of the God of the universe!

We do not honor Him by using His name so carelessly. Nor do we honor Him by insulting His creation, fallen though it is.

Man is no maggot and God is worthy of more respect than such selective and narcissistic usages.

Remember of Whom you speak!

Remember Who our great God is!

Remember and tremble and rejoice, for He has come to us now in Christ.

[1] Huizinga, Johan (2011-03-17). Erasmus and the Age of Reformation (p. 73). Kindle Edition.

[2] Francis I. Andersen, Job. Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries. 14 (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press Academic, 2008), p.231.

[3] William F. Buckley, Jr. Let Us Talk Of Many Things. (Roseville, CA: Forum Prima Publishing, 2000), 229.

[4] https://www.desiringgod.org/articles/should-i-want-to-be-such-a-worm

[5] John H. Walton, Job. The NIV Application Commentary. Gen. Ed., Terry Muck. (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2012), p.250.

[6] John E. Hartley, The Book of Job. The New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Gen. Eds., R.K. Harrison and Robert L. Hubbard, Jr. (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1988), p.365-366.

[7] John H. Walton, 254.

[8] John E. Hartley, p.366,n.21.

Pingback: Job | Walking Together Ministries