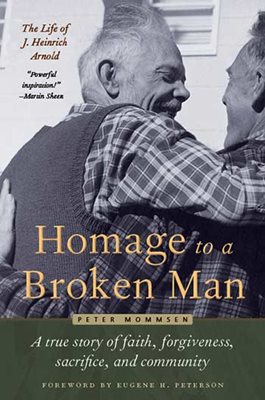

For a long time now I have been intrigued by intentional Christian communal experiments. I used to live about a half hour away from Koinonia Farms, Clarence Jordan’s community in Americus, Georgia (which, incidentally, makes a fascinating appearance in Mommsen’s book), and would go by from time to time to visit. Similarly, like many people, I have been intrigued with groups like the Amish, the Mennonites, and the Hutterites, though never uncritically so. I have been interested in the Bruderhof, a German Anabaptist group foundered by Eberhard Arnold, since I read Arnold’s anthology of patristic statements, The Early Christians: In Their Own Words, some years back. So my interest was piqued when I saw theologian Scot Mcknight tweet praises for Peter Mommsen’s Homage to a Broken Man: The Life of J. Heinrich Arnold.

For a long time now I have been intrigued by intentional Christian communal experiments. I used to live about a half hour away from Koinonia Farms, Clarence Jordan’s community in Americus, Georgia (which, incidentally, makes a fascinating appearance in Mommsen’s book), and would go by from time to time to visit. Similarly, like many people, I have been intrigued with groups like the Amish, the Mennonites, and the Hutterites, though never uncritically so. I have been interested in the Bruderhof, a German Anabaptist group foundered by Eberhard Arnold, since I read Arnold’s anthology of patristic statements, The Early Christians: In Their Own Words, some years back. So my interest was piqued when I saw theologian Scot Mcknight tweet praises for Peter Mommsen’s Homage to a Broken Man: The Life of J. Heinrich Arnold.

J. Heinrich Arnold was the son of Eberhard Arnold and the grandfather of Peter Mommsen, this author. In many ways, Arnold’s story is the story of the Bruderhof: its humble beginnings in Germany as an intentional experiment in living out the sermon on the mount, its move to England during Hitler’s ascendancy to power, its journey to Paraguay and the creation of the Bruderhof community Primavera, and its expansion to the United States, particularly to upstate New York where Arnold really came into his own as a community leader.

On one level, then, this is a story about a particular Christian community and, on another level, it is the broader story of intentional Protestant communal experiments in particular. All of the good and bad elements that seem to come with these efforts are here: the charismatic founder, the initial simple efforts to live out the teachings of Jesus in a literal way, growth and expansion, the challenge of critiques from the outside and disillusionment on the inside, the rise of power figures, the death of the original founder and the question of succession, the encroachment of a dictatorship in the guise of a strong and charismatic second-generation leader, conflict, the call to return to the original founding vision of the community from those who still hold to the founding vision, the challenges and dynamics of geographic expansion, an exodus by those who grow disillusioned, etc. etc. The story of these kinds of communities usually include most if not all of these elements. However, if the community has enough people who hold to the original vision, who are willing to be patient and long-suffering with human failure, who do not flee when the idealized vision is shattered, and, above all else, who keep promoting Christ as the head and center of the community, it can survive and it can begin to become a genuine expression of Christian communal life.

The story of Heinrich Arnold in particular is a fascinating tale of one man’s journey through these various facets of the Bruderhof’s life. He was the son of the founder and, to his dying day, evidenced the marked impact that his father had on his life. For example, inspired by this book I recently acquired and finished Heinrich Arnold’s Freedom From Sinful Thoughts (with a Foreword, I note, from John Michael Talbot). Heinrich frequently and positively quotes his father throughout this wonderful little book.

The central conflict of the story is the conflict between Arnold and Hans, his brother-in-law, who became the leader of the Bruderhof. In Mommsen’s telling, Hans rose to power in the Bruderhof through the strength of his own charisma and also through certain acts of political intrigue. He became a profoundly polarizing figure who seems to have held a special grudge against Heinrich, perhaps because of the latter’s popularity among the people of the community, especially the children. Hans and some of his colleagues were the source of much suffering for Heinrich and his family. In the end, however, when the crisis reached a boiling point, Heinrich and some of his colleagues were effectively able to remove Hans. In the wake of doing so, the true extent of Hans’ deficiencies and duplicities came to light. It is a jarring and enthralling story.

I hasten to add two things. First, I was aware throughout that I was reading the story as told by the grandson of Heinrich Arnold. The book is extremely well written, and it seems that great pains were taken to tell the story accurately, but it should be noted that Mommsen is indeed the grandson of the character who comes out looking the best. Secondly, however, I want to add that Mommsen’s telling does not read like hagiography and I detected no signs of romanticization of the story in favor of his grandfather, even given that Heinrich emerges from the story in the most favorable light. What is more, Mommsen’s frequently points to his grandfather’s testimony of his own flaws and shortcomings. Which is simply to say this: a grandson cannot help but be a grandson, but there is a great deal of evidence here that Mommsen has told the story fairly, evenly, and without an axe to grind. In fact, I would say that Mommsen has done an absolutely fantastic job of removing himself and any agenda from this telling and that he has done a great job of walking the line between being an objective chronicler of a story and being a participant in it.

This is an amazing and inspiring book. I was deeply moved by it. It is a story about the inevitable problems that come when human beings try to live life together. It is a cautionary tale about power. Above all else, it is a story about the triumph of the gospel, of forgiveness, and of the power of Jesus to shape us and mold us into His image. Furthermore, it is a fascinating character study of one man’s life. The story of J. Heinrich Arnold will move you and challenge you. His willingness to forgive, his willingness to endure hardship, his journey to become Christlike in his own character, his love of children, his love of his wife, his love of his family: these will all leave a deep impression on you.

This is a great book.

[A final statement about the Bruderhof. If one searches online for information about the Bruderhof one will quickly find websites saying that it is a cult, that it is controlling, etc. I would like to make it clear that I have very little knowledge of the Bruderhof in its current form and am neither advocating it as a body or seeking to make a negative statement about it. This is a review of a book about the son of the founder of that community, nothing more. I remain fully aware the inherent dangers that come with these kinds of communal experiments even as I appreciate their strengths. In conclusion, I remain conflicted.]

I, too, just finished reading this book. I have read just about everything there is to read on the Internet, both good and horribly bad, about the Bruderhof and consider myself to be one of its many distant friends. My wife and I spent a couple of years in a similar community shortly after being married and, though wary of the Bruderhof’s practices, I have had considerable interest in them and voraciously absorbed any morsel of information about them for 40+ years. Along with what I view as considerable change having occurred in their communities now that they have embraced the Web by producing videos and podcasts which invite people to check them out and seem to portray them as “normal” and approachable people, I note that most of the negative experiences described and still online occurred 30+ years ago. That Plough even published this book by one of the Bruderhof’s younger leaders — could that be an indicator of a new openness and tolerance in might have been discouraged before? I really like to think so.

Thank you, Mike, for this very helpful comment. That is most interesting…and hopeful! There is no reason in and of itself that such intentional communities should not exist and thrive, except, of course, for the obvious reason of human sinfulness. Though I am outside the Bruderhof, I certainly wish them well!