Exodus 23

Exodus 23

10 “For six years you shall sow your land and gather in its yield, 11 but the seventh year you shall let it rest and lie fallow, that the poor of your people may eat; and what they leave the beasts of the field may eat. You shall do likewise with your vineyard, and with your olive orchard. 12 “Six days you shall do your work, but on the seventh day you shall rest; that your ox and your donkey may have rest, and the son of your servant woman, and the alien, may be refreshed. 13 “Pay attention to all that I have said to you, and make no mention of the names of other gods, nor let it be heard on your lips. 14 “Three times in the year you shall keep a feast to me. 15 You shall keep the Feast of Unleavened Bread. As I commanded you, you shall eat unleavened bread for seven days at the appointed time in the month of Abib, for in it you came out of Egypt. None shall appear before me empty-handed. 16 You shall keep the Feast of Harvest, of the firstfruits of your labor, of what you sow in the field. You shall keep the Feast of Ingathering at the end of the year, when you gather in from the field the fruit of your labor. 17 Three times in the year shall all your males appear before the Lord God. 18 “You shall not offer the blood of my sacrifice with anything leavened, or let the fat of my feast remain until the morning. 19 “The best of the firstfruits of your ground you shall bring into the house of the Lord your God. “You shall not boil a young goat in its mother’s milk.

One of the more difficult questions to try to answer is the question, “What is religion?” Richard John Neuhaus once made an admirable attempt at it after being questioned on the topic.

Religion, from religere, has to do with what is binding, what holds things together. I would venture a definition somewhat along these lines: A religion combines (1) a more or less systematic correlation of beliefs that purports to offer a comprehensive explanation of reality, (2) the practical truths normative for living in accord with that reality, and (3) the practices or rituals that provide a measure of communion with the vital center of that reality.[1]

That is helpful. Neuhaus also offered an interesting definition of “religion” from a friend of his, Marc Gellman.

Marc Gellman, a friend who bills himself as the only pro-life Reform rabbi in the country, is a gifted writer of children’s books and is currently working on a book that introduces kids to the world religions. He thought and thought about what it is that all religions have in common. He finally came up with four components. Everything that we call a religion has (1) a story about how the world came to be and what it is for; (2) a code for living the moral life; (3) an answer to the problem of death. And the fourth? Every religion uses candles. We’re thinking about it.[2]

Again, it is a tricky question, given the wide range of things that claim the title “religion.” It is interesting to note, however, that both Neuhaus and Gellman mention ritualistic elements. Neuhaus’ “practices or rituals” and Gellman’s “candles” refer to the same element of religion: external rites or rituals that communicate something foundational to the faith.

Followers of Jesus believe that there is only one God and that He is the God who revealed Himself first through the people of Israel and then, definitively, through the person and fulfilling work of Christ Jesus. Christians are hesitant to speak of Christianity as a religion. We prefer to speak of it as a relationship with the living God. Even so, both in ancient Judaism and in modern Israel there are elements that are external in their nature, and they do in fact speak of the core of our faith.

In Exodus 23:10-19, we see guidelines for Israel’s ritual observance of the faith. We speak of these in two general ways: first in terms of Sabbath rhythms and secondly in terms of acts of sacred remembrance.

The people of God need to keep the Sabbath rhythms.

The Sabbath is rooted in creation itself. In the beginning of Genesis 2, for instance, we read:

1 Thus the heavens and the earth were finished, and all the host of them. 2 And on the seventh day God finished his work that he had done, and he rested on the seventh day from all his work that he had done. 3 So God blessed the seventh day and made it holy, because on it God rested from all his work that he had done in creation.

We rest on the Sabbath because God rested on the Sabbath. In doing so, God established a six-days-on-seventh-day-off rhythm. Eugene Peterson’s thoughts on Sabbath rhythm are worth heeding at this point.

Sabbath means quit. Stop. Take a break. Cool it. The word itself has nothing devout or holy in it. It is a word about time, denoting our nonuse of it, what we usually call wasting time.

Sabbath extrapolates this basic, daily rhythm into the larger context of the month. The turning of the earth on its axis gives us the basic two-beat rhythm, evening/morning. The moon in its orbit introduces another rhythm, the twenty-eight-day day month, marked by four phases of seven days each. It is this larger rhythm, the rhythm of the seventh day, that we are commanded to observe. Sabbath-keeping presumes the daily rhythm, evening/morning. We can hardly avoid stopping our work each night as fatigue and sleep overtake us. But we can avoid stopping work on the seventh day, especially if things are gaining momentum. Keeping the weekly rhythm requires deliberate action. Sabbath-keeping often feels like an interruption, an interference with our routines. It challenges assumptions we gradually build up that our daily work is indispensable in making the world go. And then we find that it is not an interruption but a more spacious rhythmic measure that confirms firms and extends the basic beat. Every seventh day a deeper note is struck – an enormous gong whose deep sounds reverberate berate under and over and around the daily timpani percussions of evening/morning, evening/morning, evening/morning: creation honored and contemplated, redemption remembered and shared.[3]

This 6 days/7th day rhythm is sacred and vitally important. Interestingly, our text extends it into other areas of Israel’s life.

10 “For six years you shall sow your land and gather in its yield, 11 but the seventh year you shall let it rest and lie fallow, that the poor of your people may eat; and what they leave the beasts of the field may eat. You shall do likewise with your vineyard, and with your olive orchard.

Here we see the 6/7th rhythm extended beyond days to years. Just as we are to observe the Sabbath every seventh day, so too the fields themselves are to have Sabbath rest every 7th year. The stated reason is so “that the poor of your people may eat; and what they leave the beasts of the field may eat.” So on the seventh year, the fallow fields will offer refreshment to the poor and to the beasts. Interestingly, The IVP Bible Background Commentary on the Old Testament says it is most “likely that Israelite farmers set aside as fallow one-seventh of their fields each year rather than leaving all of their land fallow for an entire year.”[4]

Even so, the important point is that Sabbath rhythm was extended to the land itself in order to provide for the poor. This last point is essential, for it shows that this was no mere custom or ritual. It was profoundly humanitarian in its focus. Terence Fretheim observes that “ritual here has not become ritual for its own sake but in the service of wider human concerns” and further notes that “this same prioritization is enunciated by Jesus: The Sabbath was made for people, not people for the Sabbath (Mark 2:27).”[5]

The same concern for others is spoken of in verse 12.

12 “Six days you shall do your work, but on the seventh day you shall rest; that your ox and your donkey may have rest, and the son of your servant woman, and the alien, may be refreshed.”

Consider the beneficiaries of this Sabbath rest:

- your ox

- your donkey

- the son of your servant woman

- the alien

Truly these are “the least of these.” This is important because it means that the Sabbath is not only there to benefit you. It is also there to benefit the poor, the outcast, and even your animals. There is a missionary heart at the center of the Sabbath.

The final statement drives the importance of the point home:

13 “Pay attention to all that I have said to you, and make no mention of the names of other gods, nor let it be heard on your lips.”

What this most certainly is not is a general theological statement about monotheism in the midst of Sabbath rhythm regulations. On the contrary, by placing it here, the Lord is telling us that Sabbath observance is a matter of obedience to the Lord God. To reject the observance of God-ordained Sabbath rhythms is to reject the God who ordained the rhythms.

The people of God need to keep the sacred remembrances of their own salvation through acts of celebration, sacrifice, and offering.

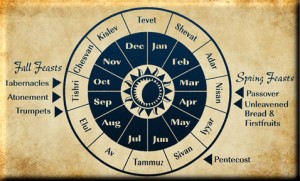

Next we find regulations on feast and festival days as well as offerings. The calendar of Israel was shot through with festivals and feasts intended to remind the children of Israel of God’s great work of salvation. The Anchor Bible Dictionary lists the festivals of Israel like this:

- January 1-12: a special offering

- January 14: Passover

- January 15-21: Festival of Unleavened Bread

- February 14: the second Passover

- March ?: The Festival of Weeks

- July 1: a day of solemn rest

- July 10: The Day of Atonement

- July 15-21: The Festival of Tabernacles[6]

This is just an overview of some of Israel’s prescribed observances. Our text mentions three in particular: the feasts of Unleavened Bread, Harvest, and Ingathering. “Though it is impossible…to fix with certainty the months for these festivals,” writes Victor Hamilton, “the following is a good approximation: (a) Festival of Flatbread/ Unleavened Bread, April; (b) Festival of the Harvest, late May or early June; (c) Festival of Ingathering, late September or early October.”[7]

The Feast of Unleavened Bread

The first feast mentioned was a feast intended to remind Israel of their deliverance out of Egypt.

14 “Three times in the year you shall keep a feast to me. 15 You shall keep the Feast of Unleavened Bread. As I commanded you, you shall eat unleavened bread for seven days at the appointed time in the month of Abib, for in it you came out of Egypt. None shall appear before me empty-handed.

This feast was a physical rite whereby Israel recalled their salvation out of the bitter, dark years of slavery and bondage in Egypt. The eating of the unleavened bread took them back in heart, mind, and soul to that generation of Jews who did this very thing as they prepared for their miraculous exit from Pharaoh’s empire. This, then, was a feast of remembrance.

The Feast of Harvest

The next is a feast of thanksgiving for God’s provision.

16a You shall keep the Feast of Harvest, of the firstfruits of your labor, of what you sow in the field.

This feast is a feast that redeems the ordinary. It reminded Israel not of a miraculous exodus but rather of the daily provision of God. This, too, is a miracle, of course. This feast reminded Israel that God is ever and always providing for them, caring for them, and causing the earth itself to offer them sustenance.

The Feast of Ingathering

The same could be said of the Feast of Ingathering.

16b You shall keep the Feast of Ingathering at the end of the year, when you gather in from the field the fruit of your labor.

This feast celebrated God’s sustaining of the people of Israel through their storehouses of plenty. Not only in the harvesting of the fields but also in the ingathering of the yield is the love and provision of God made known.

The Purity of Sacrifice and Offering

Our text ends with some further stipulations on these observances and remembrances.

17 Three times in the year shall all your males appear before the Lord God. 18 “You shall not offer the blood of my sacrifice with anything leavened, or let the fat of my feast remain until the morning. 19 “The best of the firstfruits of your ground you shall bring into the house of the Lord your God. “You shall not boil a young goat in its mother’s milk.”

In short, we might say that these regulations speak to the need for consistency and purity in observance. They were safeguards against flippant or casual degradations of these sacred times. They reminded the people of God that their offerings should be the best they have.

The last phrase, “You shall not boil a young goat in its mother’s milk,” is particularly intriguing. It is, to our ears, odd, but it speaks of an important point nonetheless. I here quote Victor Hamilton at length to help us understand some of the various theories that have been proposed to understand these words.

“You shall not boil a kid in its mother’s milk” is a verse, or a portion of a verse, that reappears in Exod. 34: 26b (also at the end of a cultic calendar), and in Deut. 14: 21b (at the end of a list of edible and inedible food). It is a verse that has had tremendous influence in later Judaism in providing the biblical rationale for separating dairy products from meat products in a kosher food system. For example, Targum Onqelos simply renders the verse, “You shall not eat meat with/ in milk.”…

Before I get to three of the main interpretations of this law, let me briefly mention two recent and innovative suggestions. First, Labuschagne (1992) suggests that the reason for the prohibition is that when the new mother cow first gives her milk to her young, the milk has a yellowish or reddish tinge to it, making it look like blood. This is because of the cow’s “beastings/ beestings” or “colostrum,” which my dictionary defines as “a yellow fluid rich in protein and immune factors, secreted by the mammary glands during the first few days of lactation.” And we all know what the Bible says about not eating the blood (Gen. 9: 4; Lev. 7: 26– 27; 17: 10– 12; Deut. 12: 16, 23; 15: 23; Acts 15: 20). But it is not blood: the fluid only looks like blood.

A second innovative interpretation is offered by J. Sasson (2002; 2003). The Hebrew words for “fat” and “milk” have the same three consonants (ḥ-l-b), except that the vowels are different: ḥēleb (“fat”) versus ḥālāb (“milk”). Sasson suggests that in Exod. 23: 19b we read “fat” (ḥēleb) instead of “milk” (ḥālāb), and so the verse says, “You shall not boil a kid in its mother’s fat.” Would, then, boiling/ cooking the kid in the father’s fat be acceptable? And is not the fat of any animal, male or female, to be offered to the Lord (Lev. 7: 23– 24) and not for human consumption, unless it is wild game (17:13–14)?

Here are three other possibilities, more commonly suggested than the two above. First, maybe this verse is directed at a pagan, Canaanite cultic practice. Support for this view has come in a Ugaritic text from Ras Shamra (1400– 1200 BC). It is a line in CTA 23.14, part of a larger text often identified as “The Gods Fair and Beautiful.” The line is ṭb[ ḥ g] d bḥlb annḫ bḫmat, “Coo[k a ki] d in milk, a lamb(?) in butter.” As is seen with my square brackets, ḥ must be added to the first word and g to the second. Apart from the guess at filling in the missing letters is that (1) ṭbḥ, even if correct, means “slaughter” and not “cook,” and (2) these Canaanite texts put a word divider between words that looks like a period, and such a word divider follows the b in tb, so the restoration cannot be ṭbḥ. Finally, if the proposed reading is correct, there is no mention about cooking the kid in its mother’s milk, just cooking it in milk.

A second suggestion is humanitarian. It would be unnecessarily cruel to boil a kid in its mother’s milk, as it would be to slaughter a mother and its young on the same day (Lev. 22: 28), or to slaughter a newborn during the first week of its life (22: 27), or take the mother bird together with her offspring (Deut. 22: 6– 7). But if humanitarianism and kindness to animals is the motive, why is the prohibition not extended to all young animals? And true, one may not slaughter a mother and her young on the same day (Lev. 22: 28), but one could slaughter them on successive days. True, one may not slaughter a newborn during the first week of its life (Lev. 22: 27), but by the eighth day one may, even though the animal is still a suckling. So where is the kindness to young animals in these instances?

A third view, and the one I embrace, takes its start from a comment by Philo (Virt. 143): “[It is] grossly improper that the substance which fed the

living animal should be used to season and flavor the same after its death…Man [should not] misuse what has sustained its life.” Do not use, says this law, something that brings life (milk for sustenance) to bring death (milk for cooking). Alter (2004: 452) calls “the mixture of the mother animal’s nurturing milk with the slaughtered flesh of her offspring a promiscuous joining of life and death.” What brought life now brings death, and that is not right. It is like religion, one of whose purposes is to bring life and tranquility and joy, but alas, it has often been used to bring death and chaos and sorrow.[8]

This is all very fascinating and helpful. Let me suggest that there is something to be said about this final view, Hamilton’s own view. There is something macabre in boiling a young goat in its mother’s milk. There is something unsettling about it. Let us keep in mind that the wider text is speaking of the need to provide both humans and animals rest. Our text has spoken of the beauty and goodness of God’s provision for humanity through the created order. It has spoken of the bounty of the earth. Could it not be that the Lord is here saying that taking the milk of life and boiling a mother’s young in it for the gratification of our own appetites seems to violate the very spirit of Sabbath rest, sacred remembrance, and gratitude? Could it not be that the Lord is cautioning us against such “a promiscuous joining of life and death” because there is something violating about it, something lacking gratitude, something unseemly in its decadence?

What are modern Christians to make of these Sabbath rhythm stipulations and these festival regulations? Is it not the case that Christ Jesus has also left us the call to Sabbath rest and the call to sacred remembrance? In terms of physical rites, can we too not violate the sacredness of the baptismal waters and the communion elements by being flippant and overly casual? Can we not also violate the sacredness of the Lord’s table by not observing it consistently enough? Indeed we can.

Christianity is not a religion, but it does have certain rites, and those rites, like the feasts and festivals of Egypt, are tied to the central saving act of God in Christ as well as to the “ordinary” provisions of God for us through the created order. If we are not aware of this and careful about it, we too can offend the glory of God.

No word of Scripture is wasted, even the enigmatic words. We should sit with Israel, listen, and heed what the Spirit is saying to the Church.

Observe and honor the rhythms of Sabbath rest.

Kept the sacred remembrances with consistency and purity.

Let all of these stoke within us a true and unwavering love for Jesus.

[1] Richard John Neuhaus, “While We’re At It,” First Things. January 1997.

[2] Richard John Neuhaus. “While We’re At It.” First Things. November 1994.

[3] Eugene H. Peterson. Working the Angles: The Shape of Pastoral Integrity (Kindle Locations 663-700). Kindle Edition.

[4] John H. Walton, Victor H. Matthews and Mark W. Chavalas, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000), p.103.

[5] Terence E. Fretheim, Exodus. Interpretation (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), p.251.

[6] David Noel Freedman, Editor, A-C. The Anchor Bible Dictionary. Vol.1 (New York, NY: Doubleday, 1992), p.815-816.

[7] Hamilton, Victor P. (2011-11-01). Exodus: An Exegetical Commentary (Kindle Locations 13582-13584). Baker Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

[8] Hamilton, Victor P., Kindle Locations 13617-13659.

Pingback: Exodus | Walking Together Ministries