Genesis 22

1 After these things God tested Abraham and said to him, “Abraham!” And he said, “Here I am.” 2 He said, “Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains of which I shall tell you.” 3 So Abraham rose early in the morning, saddled his donkey, and took two of his young men with him, and his son Isaac. And he cut the wood for the burnt offering and arose and went to the place of which God had told him. 4 On the third day Abraham lifted up his eyes and saw the place from afar. 5 Then Abraham said to his young men, “Stay here with the donkey; I and the boy will go over there and worship and come again to you.” 6 And Abraham took the wood of the burnt offering and laid it on Isaac his son. And he took in his hand the fire and the knife. So they went both of them together. 7 And Isaac said to his father Abraham, “My father!” And he said, “Here I am, my son.” He said, “Behold, the fire and the wood, but where is the lamb for a burnt offering?” 8 Abraham said, “God will provide for himself the lamb for a burnt offering, my son.” So they went both of them together. 9 When they came to the place of which God had told him, Abraham built the altar there and laid the wood in order and bound Isaac his son and laid him on the altar, on top of the wood. 10 Then Abraham reached out his hand and took the knife to slaughter his son. 11 But the angel of the Lord called to him from heaven and said, “Abraham, Abraham!” And he said, “Here I am.” 12 He said, “Do not lay your hand on the boy or do anything to him, for now I know that you fear God, seeing you have not withheld your son, your only son, from me.” 13 And Abraham lifted up his eyes and looked, and behold, behind him was a ram, caught in a thicket by his horns. And Abraham went and took the ram and offered it up as a burnt offering instead of his son. 14 So Abraham called the name of that place, “The Lord will provide”; as it is said to this day, “On the mount of the Lord it shall be provided.” 15 And the angel of the Lord called to Abraham a second time from heaven 16 and said, “By myself I have sworn, declares the Lord, because you have done this and have not withheld your son, your only son, 17 I will surely bless you, and I will surely multiply your offspring as the stars of heaven and as the sand that is on the seashore. And your offspring shall possess the gate of his enemies, 18 and in your offspring shall all the nations of the earth be blessed, because you have obeyed my voice.” 19 So Abraham returned to his young men, and they arose and went together to Beersheba. And Abraham lived at Beersheba. 20 Now after these things it was told to Abraham, “Behold, Milcah also has borne children to your brother Nahor: 21 Uz his firstborn, Buz his brother, Kemuel the father of Aram, 22 Chesed, Hazo, Pildash, Jidlaph, and Bethuel.” 23 (Bethuel fathered Rebekah.) These eight Milcah bore to Nahor, Abraham’s brother.24 Moreover, his concubine, whose name was Reumah, bore Tebah, Gaham, Tahash, and Maacah.

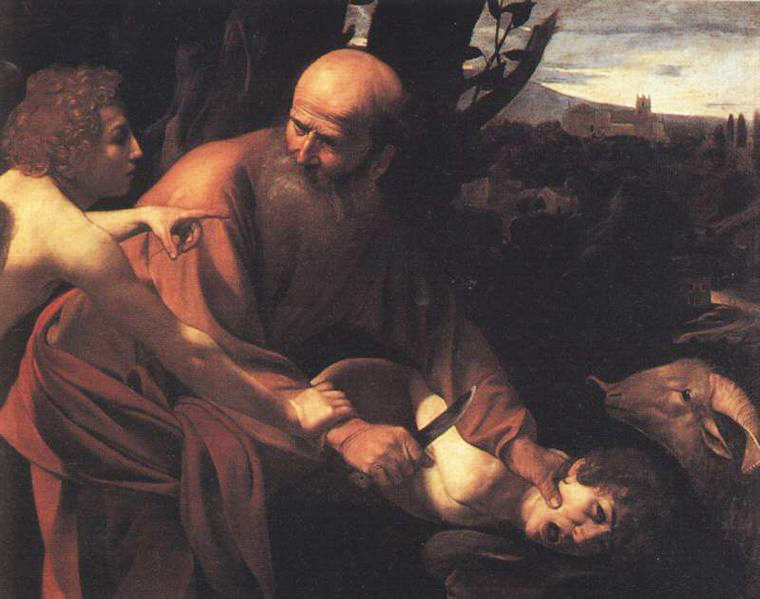

I am certainly no art expert, but I have long had a deep appreciation and admiration for the work of Caravaggio. For instance, I find his famous “The Incredulity of Saint Thomas,” depicting Thomas exploring the wound in Christ’s side after the resurrection, to be simply overwhelmingly powerful and evocative. Another of his paintings that is profoundly moving is his 1603 work, “The Sacrifice of Isaac” which is usually attributed to Caravaggio.

Wikipedia’s little summary of the painting is helpful:

The second Sacrifice of Isaac is housed in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. According to the early biographer Giovanni Bellori, Caravaggio painted a version of this subject for Cardinal Maffeo Barberini, the future Pope Urban VIII, and a series of payments totaling one hundred scudi were made to the artist by Barberini between May 1603 and January 1604. Caravaggio had previously painted a Portrait of Maffeo Barberini, which presumably pleased the cardinal enough for him to commission this second painting.

Isaac has been identified as Cecco Boneri, who appeared as Caravaggio’s model in several other pictures. Recent X-ray analysis showed that Caravaggio used Cecco also for the angel, and later modified the profile and the hair to hide the resemblance.

What strikes me most about the painting is the force and motion of it. Elderly Abraham is pinning distraught Isaac’s head to the sacrificial altar, the knife advancing toward his throat. It seems to me that the focal point of the painting is Abraham’s face. He looks like a man who has taken such pains to make a decision to do something he does not want to do that he is actually somewhat irritated to be thwarted in his effort, even though he was certainly relieved. His brow is furrowed, the eyebrows set, yet even in the painting you can see the pain behind his eyes. The angel is to his right restraining his knife hand and pointing with his left index finger to the caught ram whose head is just beside Isaac’s. Once you know that the same model posed for Isaac as for the angel you can see it, even with the different hair. Thus, in the painting, when surprised Abraham looks up to see the angel, he is seeing, along with the viewer of the painting, the face of his son.

My goodness, what a painting! The characters are each and every one a story: Abraham, Isaac, the Lord (speaking through the angel). I would like for us to consider each of these characters and, as we do so, I would like for us to consider the “lower story” and “upper story” truths we find there. That is, what do we see in each character in the “lower story” of the actual events and what do we see in them in the “upper story” of the grand, overarching narrative of salvation history.

Isaac

Lower Story: Obedience to his Father

Upper Story: Foreshadowing of the Cross

We begin with Isaac. The “lower story” of Genesis 22 involves the son of promise, Isaac, Abraham and Sarah’s boy, being taken to Mount Moriah where he would be sacrificed. Isaac did not know what was happening. This is evident in his questioning of his father.

6 And Abraham took the wood of the burnt offering and laid it on Isaac his son. And he took in his hand the fire and the knife. So they went both of them together. 7 And Isaac said to his father Abraham, “My father!” And he said, “Here I am, my son.” He said, “Behold, the fire and the wood, but where is the lamb for a burnt offering?” 8 Abraham said, “God will provide for himself the lamb for a burnt offering, my son.” So they went both of them together. 9 When they came to the place of which God had told him, Abraham built the altar there and laid the wood in order and bound Isaac his son and laid him on the altar, on top of the wood.

There is an interesting question concerning Isaac’s age in Genesis 22. Victor Hamilton unpacks the issue surrounding this question nicely:

…Isaac does not appear to be a newborn or a toddler in ch.22. Yet Abraham’s reference to Isaac na’ar, a “lad” (v.5), suggests that Isaac is not a man who is physically in the prime of life. Then again, to one who has reached the century mark the term na’ar would understandably have a broad range. Early Jewish tradition…suggested that Isaac was 37 at the time of his binding by Abraham. This number is arrived at by subtracting the age at which Sarah gave birth to Isaac (90) from the age at which she died (127), a sudden death caused by discovering that Abraham is about to slaughter Isaac.[1]

The theory of Isaac being thirty-seven works only if Sarah’s death in chapter 23 follows immediately after the events of chapter 22, and, of course, the text does not say that is so. Thirty-seven seems old, but, then again, as Hamilton points out, to a man of a hundred years a thirty-seven-year-old is certainly a “lad” still. That Isaac was old enough to carry “the wood of the burnt offering” is a helpful clue. We can at least rule out Isaac being a very small boy. Other than that, who can say.

But what of Isaac’s behavior in this story? Can we derive anything from his passive state in the narrative? I think so. We can first see his faith and obedience. He trusts his father. More than that, however, there is no sign that he resists his father. There are hints, then, that Isaac’s faith extended even to his very placement on the altar. Hamilton again helpfully observes:

It should not go unnoticed that Isaac makes no attempt to deter his father. He had asked, “Where is the sheep?” but he does not ask “Why these ropes?” If Abraham displays faith that obeys, then Isaac displays faith and cooperates. If Isaac was strong enough and big enough to carry wood for a sacrifice, maybe he was strong and big enough to resist or subdue his father.[2]

Isaac, in Genesis 22, is a picture of trust and obedience. We never see a Gethsemane moment for Isaac, a “If there be any other way, father…yet not my will but thine be done” moment. Perhaps it happened internally. Perhaps he never really had time for such a moment. Perhaps the reality of the situation only hit him when his father bound him and lifted him to the altar. We are forced to wonder about such details. Regardless, what we do have is the text’s depiction, and, in it, Isaac is depicted as accepting and as submitting. He resigns himself to his father’s will, even as, undoubtedly, he struggles to understand.

But what of the “upper story” of Isaac’s place in Genesis 22? Christian interpreters have been quick to point out that Isaac carrying the wood of the sacrifice is a powerful foreshadowing of Christ carrying His own cross to Golgotha. In both stories the son who is to be sacrificed is laden with the instrument of his own death and carries it up a hill.

Interestingly, verse 2 tells us that all of this happened on the mountain in Moriah. Derek Kidner observes that “Moriah reappears only in 2 Chronicles 3:1, where it is identified as the place where God halted the plague of Jerusalem and where Solomon built the temple. In New Testament terms, this is the vicinity of Calvary.”[3]

Scholars argue about whether the Moriah mentioned in Genesis 22 could be the Moriah, the vicinity of Jerusalem, mentioned in 2 Chronicles 3. For our purposes, the point simply needs to be made that the only other reference to the place in scripture refers to “the vicinity of Calvary.” Meaning, this might have been the very area where Christ Himself was crucified, where Christ Himself carried the wood up the hill.

Abraham

Lower Story: Radical Trust

Upper Story: The Painful Giving of the Son

Then, of course, we have Abraham, Isaac’s father. The pain of Abraham at God’s command must have been unbelievable, yet Abraham’s radical trust in God simply stops us in our tracks.

1 After these things God tested Abraham and said to him, “Abraham!” And he said, “Here I am.” 2 He said, “Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains of which I shall tell you.” 3 So Abraham rose early in the morning, saddled his donkey, and took two of his young men with him, and his son Isaac. And he cut the wood for the burnt offering and arose and went to the place of which God had told him.

What did it mean for God to tell Abraham to kill Isaac? It meant the end of a dream that he had to wait one hundred years to see fulfilled. It meant, certainly, the destruction of his marriage as we would have to tell Sarah his wife that he had killed their child. More than that, it meant the end of God’s promise that he seems to have finally come to trust. It also meant the end of his family name. God had promised that Abraham would have a lineage through Isaac specifically. The death of Isaac meant the death of all of that.

“Abraham had to cut himself off from his whole past in ch. 12.1 f.; now he must give up his whole future…” wrote Gerhard von Rad. von Rad continued thus:

Isaac is the child of promise. In him every saving thing that God has promised to do is invested and guaranteed. The point here is not a natural gift, not even the highest promise…It has to do with a road out into Godforsakenness, a road on which Abraham does not know that God is only testing him.[4]

Yes, despite Abraham’s amazing display of faith, what would become of his relationship with God after he, in obedience to God, took the life of his own son? Yet Abraham’s faith is staggering! Verse 3 depicts a simple obedience that one struggles to comprehend.

3 So Abraham rose early in the morning, saddled his donkey, and took two of his young men with him, and his son Isaac. And he cut the wood for the burnt offering and arose and went to the place of which God had told him.

The verbs depict his great obedience. Abraham rose…Abraham saddled his donkey…Abraham took two young men…Abraham took his son Isaac…Abraham cut wood…Abraham arose…Abraham went. For any of us there would be other verbs in that list, no?

Abraham protested!

Abraham wept!

Abraham screamed!

Abraham raged!

Abraham rejected!

Abraham fled!

But no, none of that. Abraham obeyed! See in Abraham the very picture of radical trust! In fact, in Hebrews 11 we find that Abraham’s obedience rested at least in part in the fact that he believed God would resurrect Isaac after he killed him.

17 By faith Abraham, when he was tested, offered up Isaac, and he who had received the promises was in the act of offering up his only son, 18 of whom it was said, “Through Isaac shall your offspring be named.” 19 He considered that God was able even to raise him from the dead, from which, figuratively speaking, he did receive him back.

This is great faith indeed! And what of the upper story? What does the figure of Abraham tell us about the story of salvation history. In Abraham we find the father’s pain at giving the son. We see the father’s great sacrifice in offering up his child of promise.

Think of the pain that Abraham felt at the thought of killing his son. Think of the heartbreak that command must have brought. Think of the agony of that moment! Think of the pain of that moment!

Then stop and think of the pain of God the Father giving His only begotten Son to be crucified at the hands of wicked men.

The pain of Abraham is a pale reflection of the pain of God at giving His Son, Jesus. On the upper story, we are drawn into the agony of Abraham so that our hearts might be better equipped to ponder the agony, if you will, of the Father at sending Jesus.

John Stott writes:

George Buttrick wrote of a picture that hangs in an Italian church, although he did not identify it. At first glance it is like any other painting of the crucifixion. As you look more closely, however, you perceive the difference, because “there’s a vast and shadowy Figure behind the figure of Jesus. The nail that pierces the hand of Jesus goes through to the hand of God. The spear thrust into the side of Jesus goes through into God’s.”[5]

There is a sense in which the pain of the cross is the Father’s pain as well, for the Father and the Son are one, and while we must be careful to be clear what we mean when we speak of the agony or pain of the Father in giving the Son, we may rightly use the word to describe the dynamic that arose when death entered a relation defined by the kind of love that Jesus mentioned in John 17:

20 “I do not ask for these only, but also for those who will believe in me through their word, 21 that they may all be one, just as you, Father, are in me, and I in you, that they also may be in us, so that the world may believe that you have sent me.22 The glory that you have given me I have given to them, that they may be one even as we are one, 23 I in them and you in me, that they may become perfectly one, so that the world may know that you sent me and loved them even as you loved me. 24 Father, I desire that they also, whom you have given me, may be with me where I am, to see my glory that you have given me because you loved me before the foundation of the world. 25 O righteous Father, even though the world does not know you, I know you, and these know that you have sent me. 26 I made known to them your name, and I will continue to make it known, that the love with which you have loved me may be in them, and I in them.”

There has never been a love like the love that God the Father has for God the Son. God was therefore, in asking Abraham to take the life of Isaac, preparing him and the world to understand just what it meant that He, God, would give His own Son to die for the sins of the world.

Michael Card has suggested the fascinating idea that the tearing of the temple veil from top to bottom (Matthew 27:51) might come from the way that Jewish patriarch’s would express grief: tearing their garments from top to bottom. “What if,” Card asks, “the rending of the veil of the Temple was God’s own lamenting response to the death of His Son?…[C]ould it be that it was a sign that God Himself was mourning the crucifixion, that He was participating in the cosmic reaction to the impossibility of Jesus’ death?”[6]

God

Lower Story: Priority and Trajectory

Upper Story: Preparing the World for Substitutionary Love

The final character, the central character, is God.

10 Then Abraham reached out his hand and took the knife to slaughter his son. 11 But the angel of the Lord called to him from heaven and said, “Abraham, Abraham!” And he said, “Here I am.” 12 He said, “Do not lay your hand on the boy or do anything to him, for now I know that you fear God, seeing you have not withheld your son, your only son, from me.” 13 And Abraham lifted up his eyes and looked, and behold, behind him was a ram, caught in a thicket by his horns. And Abraham went and took the ram and offered it up as a burnt offering instead of his son.

On the lower story, God is testing Abraham to see if Abraham truly has God as his ultimate priority. Furthermore, God is establishing a trajectory which will, paradoxically, move His people forward. That trajectory is this: we must love God more than the gifts God gives us and the moment we love the gifts God gives us more than God we have distorted those gifts into something diabolical. If Abraham and his offspring—if Israel, we should say—is going to survive all that is about to come to them and if the true intent of the covenant promises is to be fulfilled—the nations knowing and worshiping God—then there cannot be a fatal misstep here at this critical juncture. God must establish in the heart of Abraham that he simply cannot love the fulfilled promise more than the Promise Fulfiller. In asking Abraham to give up Isaac, God was asking Abraham to demonstrate that God and God alone was preeminent to him. If God was not preeminent to Abraham, then the entire forward movement of God’s people would be derailed.

But what of the upper story? What of God calling for Isaac to be sacrificed and then stopping the sacrifice He called for? First, there is an interesting linguistic clue that will help us get at what is happening here. Victor Hamilton, commenting on verse 13, writes:

Walters has observed that apart from Gen. 22 ‘burnt offering,’ ‘appear, be seen’…and ‘ram’ occur together in only two places in the OT. These are (1) the ordination of priests (Lev. 8-9, esp. 9:2-4) and the Day of Atonement (Lev. 16, esp. vv. 1, 3). Thus the ram is associated with priesthood and atonement.[7]

There is, therefore, a fairly specific formula in verse 13 that points to the coming priesthood and to the Day of Atonement, the day, that is, in which the sins of God’s people were placed on the head of a scapegoat who was then sent out of the camp. In other words, this passage has to do with substitution and atonement, with a payment for sin being made by somebody other than the one upon whom the payment was supposed to fall.

Just as Abraham goes to sacrifice Isaac, he sees there in the thicket a ram! He sees a substitute! Somebody will die in the place of his son. Somebody will die in Isaac’s stead.

The great upper story truth of Genesis 22 is that God was preparing Abraham and the whole human race for substitutionary love, for the fact that somebody would be sacrificed in our place, in our stead!

The whole upper story point of Genesis 22 is Jesus!

Jesus is the ram who dies in our place. Like the ram in the thicket Jesus is sent by God but, unlike the ram in the thicket, Jesus is not “caught in the thicket,” trying to get out. He is sent and He is in agreement with the sending. Jesus is sent but Jesus also comes.

Amazing love! Amazing grace! Jesus, the lamb of God, dies in our place. He is killed so that we need not be. He takes the judgment and the wrath so that we need never do so! Jesus is the substitute!

Isaac is a picture of Jesus in that the Son was given.

But the ram is a picture of Jesus in that the Son was the substitute.

All of these images come together to form a beautiful painting indeed: our loving God sends His only Son to die in the place of those who deserve it so that, through His death, those who deserve death might be forgiven and set free!

Amazing grace, how sweet the sound, that saved a wretch like me!

[1] Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 18-50. The New International Commentary on the Old Testament. (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1995), p.100.

[2] Victor P. Hamilton, p.110.

[3] Derek Kidner, Genesis. Tyndale Old Testament Commentary. Vol.1 (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2008), p.154.

[4] Gerhard Von Rad, Genesis. Revised Edition. The Old Testament Library. (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1972), p.239, 244.

[5] John Stott, The Cross of Christ. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2006), p.157.

[6] Michael Card, The Hidden Face of God. (Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress, 2007), p.173.

[7] Victor P. Hamilton, p.113.