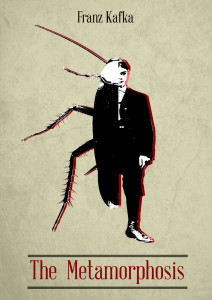

Franz Kafka’s famous short story, “The Metamorphosis,” is an enigmatic and elusive tale about a salesman named Gregor Samsa who awakens one morning to find that he has been changed into a bug. I should say instead that the tale is elusive in terms of its interpretation. The story itself, on its surface, is rather straightforward.

Franz Kafka’s famous short story, “The Metamorphosis,” is an enigmatic and elusive tale about a salesman named Gregor Samsa who awakens one morning to find that he has been changed into a bug. I should say instead that the tale is elusive in terms of its interpretation. The story itself, on its surface, is rather straightforward.

Samsa wakes up to find that he is a bug. His parents and his sister (all of whom he provides for and the last whom he adores) knock on the door in vain, as does a representative from his job who comes by to chastise him. When they finally see Gregor, they are terrified and disgusted. The remainder of the story involves the family’s failed attempts to come to terms with Gregor’s metamorphosis. The most compassionate is his sister, Greta, who feeds Gregor by leaving food in his room while he hides under a couch. Eventually, however, she too proclaims her disgust with Gregor and he dies brokenhearted.

What makes the story so intriguing is that it really does not tip its hand too much to possible meanings. Some have seen it as Kafka’s story about his own self (notice the consistent consonant/vowel structure of the names: Kafka – Samsa) and his sense of alienation from the world. Others have surmised that it might be a statement on the dehumanizing and eventual destruction of the Jews (as represented by Gregor).

It’s hard to say, though I find myself drawn to a something like a class-structure interpretation. Maybe. It seems to me that Gregor, the worker, is dehumanized, is shown a measure of pity by those who cannot understand him, and is eventually abandoned by those with brighter prospects. I am struck by the last sentence, which sees Greta stretching her blossoming body out after her parents, taking notice, reflect on the fact that they need to find her a suitable mate: “And it was like a confirmation of their new dreams and excellent intentions that at the end of their journey their daughter sprang to her feet and stretched her young body.” Thus, the book begins with a downward metamorphoses: that of a man into a bug. It ends with an upward metamorphosis: that of a girl into a beautiful young woman. The downward metamorphosis ends in dehumanization, a loss of meaning and significance, and then a death that is welcomed by the others who were so burdened by his grotesque existence. The upward metamorphoses ends in a humanization, the opening of prospects and a bright future, and a general sense of celebration by others who witness it.

On the other hand, I am struck by the note of existential despair in the story, Gregor’s horror at realizing that his very existence is a burden, that his presence is loathsome to those around him, and the utter futility of his life theretofore. Who hasn’t at time felt a bit like Gregor: alone, misunderstood, barely human?

It is a powerful little tale, and one that stays with you. I suppose the brilliance of it is that different readers can see different aspects of their own lives in the tragedy of Gregor Samsa. If you haven’t read it, you should. It’s compelling, troubling, thought-provoking, and significant.

Pingback: A 'Crime' Reflects the Conflicts in Law, Religion, and Mental Health -