Hebrews 2:5-13

5 For it was not to angels that God subjected the world to come, of which we are speaking. 6 It has been testified somewhere, “What is man, that you are mindful of him, or the son of man, that you care for him? 7 You made him for a little while lower than the angels; you have crowned him with glory and honor, 8 putting everything in subjection under his feet.” Now in putting everything in subjection to him, he left nothing outside his control. At present, we do not yet see everything in subjection to him. 9 But we see him who for a little while was made lower than the angels, namely Jesus, crowned with glory and honor because of the suffering of death, so that by the grace of God he might taste death for everyone. 10 For it was fitting that he, for whom and by whom all things exist, in bringing many sons to glory, should make the founder of their salvation perfect through suffering. 11 For he who sanctifies and those who are sanctified all have one source. That is why he is not ashamed to call them brothers, 12 saying, “I will tell of your name to my brothers; in the midst of the congregation I will sing your praise.” 13 And again, “I will put my trust in him.” And again, “Behold, I and the children God has given me.”

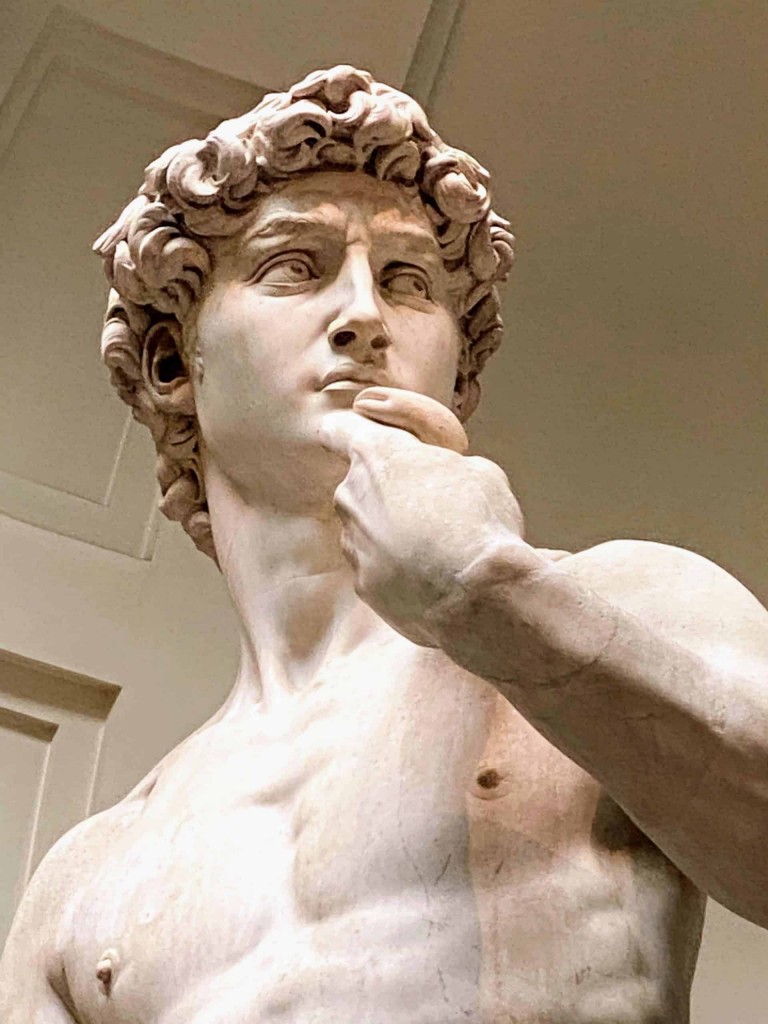

When I was in ninth grade I went on a school trip to Italy. The trip was led by mother, Diane Richardson, who was for many years the Latin teacher at Thomas Sumter Academy in Dalzell, South Carolina. It was a wonderful trip. I will never forget first seeing St. Peter’s, the Coliseum, the Pieta, the Sistine Chapel and so many other amazing creations and works of art. But what I was really unprepared for was Michelangelo’s statue of David in Florence.

The statue itself is overwhelming. It is 17 feet tall and weighs 12,000 pounds. It was carved from a single block of marble. The detail on it is stunning. I remember looking at the veins in those massive hands and thinking, “How on earth did Michelangelo do this?!” That statue is so realistic that you can imagine David simply stepping off of the pedestal and walking out into the world. It is truly amazing!

But I must say that the effect is profoundly heightened by the building in which it is placed and the journey that the viewer must go on to reach it. The statue of David is housed in Accademia Gallery in Florence. To get to the statue one must pass down a hallway known as the Hall of the Prisoners.

The hall is called this because it contains a number of unfinished statues by Michelangelo in which male figures are still imprisoned in their blocks of marble. The statues were intended to be part of what would have been another of Michelangelo’s great creations: a massive and awe-inspiring tomb for Pope Julius II. Alas, the tomb never came to be and the statues remain half-formed and imprisoned in marble.[1]

It is a powerful and somewhat disturbing experience to stand before these figures in the Hall of Prisoners. They look as if they are straining to be free, straining to be complete, pushing to break loose from the marble in which they are captured.

So the visitor to the Accademia Gallery in Florence walks down this amazing hallway studying these half-formed prisoners. But, at the end of the Hall of Prisoners, under the great dome of the Tribune, stands David: free, majestic, complete, seemingly perfect.

It is the contrast that gets you: incompletion gives way to completion, deformation gives way to formation, flaw gives way to perfection, imprisonment gives way to freedom. The Hall of Prisoners gives way to the great resplendent statue of David!

It really must be seen to be believed!

As I read Hebrews 2:5-13 my mind went back to the prisoners and to David, to this experience of passing from this hallway to the great work of art that the statue of David is. Maybe it resonated with me and, I suspect, with the vast majority of viewers because it symbolizes a tension that we all feel in our souls: the tension between what we want to be and what we really are, the tension between our aspirations and our realities, the tension between our “oughts” and our “is-es.”

We want to be David, but we feel that we are half-formed blocks of marble.

We want to be great, but we look at our lives and realize we are anything but.

Our text steps into this dynamic and tells us something important: we were made to be resplendent children of God and, though we have fallen and are marred, though we became prisoners through our sin, in Jesus we can become what God wants us to be.

But there is more. The scriptures tell us that Jesus, the perfect God-Man, stepped off of his pedestal and walked into the hall of prisoners that is the world and took on our imprisonment and our fallenness on the cross in order to set us free to become all that God intends.

Put another way: Jesus’ humility and exaltation enable and encourage the church to be more and to accept that we aremore than what the devil tells us we can be and are.

Human beings were made for greatness but in our lostness have fallen short of God’s intent for us.

We begin with a powerful fact: we were made for greatness. But fast on the heels of this is a sad fact: we have fallen into lostness. The writer of Hebrews begins to explore this in verse 5.

5 For it was not to angels that God subjected the world to come, of which we are speaking.

He says that “the world to come” is not going to be “subjected” to angels. Let us first try to understand what he means by this. Donald Guthrie has provided some helpful options.

The meaning of the world to come is a matter of debate. The Greek expression (hē oikoumenē hē mellousa) can be understood in various ways, as for instance (i) of the afterlife, (ii) of the new order inaugurated by Jesus Christ, i.e. the fulfilment of the looked for ‘age to come’ which was now come in the present kingdom of God, or (iii) of the end of the present age. There may be truth in all three, but the second seems to be brought most clearly into focus by the context. It is worth noting that the word used here for ‘world’ is not kosmos (the world as a system), but the world of inhabitants (oikoumenē).[2]

This seems reasonable enough and would fit with the overall picture of scripture, but there is a note of truth in each of these. Regardless, this authority (for the idea of subjection carries with it the idea of authority), the writer of Hebrews tells us, is nowhere given to angels.

At this point the writer pivots and I want you to not miss this: for a chapter and four verses the author of Hebrews has been examining the relationship between Jesus and the angels and has concluded definitively that Jesus is superior to the angels in every way: in His person, in His work, and in His message. But now, in verse 5, he pivots to another contrast: that which exists between angels and human beings. And he does this by appealing to a psalm, namely, Psalm 8:4-6. Watch what he does:

6 It has been testified somewhere, “What is man, that you are mindful of him, or the son of man, that you care for him? 7 You made him for a little while lower than the angels; you have crowned him with glory and honor, 8a-c putting everything in subjection under his feet.” Now in putting everything in subjection to him, he left nothing outside his control.

Now this is a fascinating thing to say. Psalm 8 is about mankind in general. The writer of Hebrews will soon apply it to Jesus but he is first making a comment about humanity. And what is this comment? It is that we were made for greatness, made to have dominion, made to have authority, made by God with His blessing and because of His image to stand on the pedestal of creation under the dome of God’s glory and rule the earth. This is what we were made for.

The psalmist in Psalm 8 and the author of Hebrews are simply repeating the great words of Genesis 1 about mankind:

26 Then God said, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness. And let them have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.” 27 So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them. 28 And God blessed them. And God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it, and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over every living thing that moves on the earth.”

Dominion. Glory. Authority. These were the qualities of humankind in creation. This is what you were made for. David on that pedestal in Florence, Italy, pales in comparison to what we were meant to be. It is enough to make us puff up our chests with pride…except that at the end of verse 8 the writer absolutely takes the wind out of our sails. He does so with precision and with devastating clarity. Look:

8d putting everything in subjection under his feet.” Now in putting everything in subjection to him, he left nothing outside his control. At present, we do not yet see everything in subjection to him.

This is one of the most precise ways of saying “Everything on earth is really messed up!” I have ever seen!

We were made to have the world subject to us…but at present we do not see what we were made to be.

Do you see this? This tension between the divine intent and the human reality, between creation and fall, between the “ought” and the “is”? My, my! Grant Osborne and George Guthrie put it like this:

The image of God in humans has been marred, and they do not have dominion. This seems an oxymoron. Humanity has universal dominion and yet doesn’t.[3]

Yes. Yes, that is so.

Jesus took the lostness of the world upon Himself on the cross.

And then we have another pivot and this one is as beautiful and awe-inspiring as the end of verse 8 is deflating and humiliating. He has just told us that we are not what we are supposed to be, that when we look at ourselves we do not see glory. Instead, when we look at ourselves we see fallenness. Then he writes:

9a But we see him…

Mercy! “But we see him…”

Some of us are constantly in a state of depression because we are fixated on ourselves and we never move on to the, “But we do see Jesus…”

The author of Hebrews is telling us that no matter how devastating the vision of ourselves might be there is a contrast in Jesus. And what do we see in Jesus? Watch:

9 But we see him who for a little while was made lower than the angels, namely Jesus, crowned with glory and honor because of the suffering of death, so that by the grace of God he might taste death for everyone.

What do we see in Jesus? We see one who is perfect and clothed in glory setting His exaltation aside. For how long? Listen to the wording: “who was made lower than the angels for a little while.” This is the incarnation of Jesus. He became a baby, born in Bethlehem. He took on flesh…“for a little while.” But more than this: “he suffered death, so that by the grace of God he might taste death for everyone.”

It is not just that Jesus stepped off the pedestal to be born. No, He also stepped off the pedestal to be killed. And for whom was He killed? He was killed “for everyone.” This is not the place for us to segue into a lengthy discussion of the extent of the atonement, that question that in so many ways is at the heart of the whole Calvinism/Arminianism controversy and all of its derivations. I will simply say this: I agree with those who point to this verse as one that plainly teaches that Christ died for all human beings and not merely for the elect. “He suffered death…for everyone.”

Though I have strong differences with Clark Pinnock on some issues, I very much agree with his assessment of those who try to limit the universal note of Hebrews 2:9. Pinnock writes of those who seek to lessen the implications of this verse:

It takes an exegetical ingenuity which is something other than a learned virtuosity to evacuate these texts of their obvious meaning: it takes an exegetical ingenuity verging on sophistry to deny their explicit universality.[4]

And what was the result for Jesus of the death of Jesus on the cross? Did death have victory over Him? Listen:

9 But we see him who for a little while was made lower than the angels, namely Jesus, crowned with glory and honor because of the suffering of death, so that by the grace of God he might taste death for everyone.

No, instead Jesus is “now crowned with glory and honor because he suffered death.”

There is an immersion here: Jesus is exalted—Jesus suffers and dies—Jesus is exalted.

Jesus exists in pre-incarnate glory—Jesus is incarnate in flesh—Jesus exists in post-resurrection glory.

And what of us? What does this great work of Jesus do for us? After Jesus steps off of the pedestal and walks into the Hall of Prisoners what does it mean for the prisoners?

Jesus now brings all who will trust in Him out of the despair of our lostness and into God’s original intent for us.

Now we move to the crescendo. Whereas previously we were told that we are far from what we were created to be, now we find the results of the work of Jesus:

10 For it was fitting that he, for whom and by whom all things exist, in bringing many sons to glory, should make the founder of their salvation perfect through suffering.

Oh my goodness what a verse! There is something about humanity here but also something about Jesus. Of humanity we are told that because Jesus humbled Himself to the cross He is now “bringing many sons and daughters to glory.” And how does He do this? He becomes the “pioneer of [our] salvation” and is made “perfect through what he suffered.”

Imagine that the statue of David steps off that pedestal under that dome and walks into the Hall of Prisoners and takes the hands of those prisoners, and pulls them out of the stone in which they have been imprisoned.

That is an awesome thought! But how about this: imagine if that majestic statue of David stepped off that pedestal, walked into the Hall of Prisoners, made himself smaller than his 17 feet and 12,000 pounds, and then entered the block of marble itself so that he could take on the imprisonment of the prisoners. Then imagine that he shatters the marble and takes the now-freed figure by the hand and walks him to the pedestal!

This is what it means that Jesus is the “pioneer” of our salvation. He has gone ahead of us and made a way. He is calling us to leave behind the prison that has held us for so long. In doing this, He has affected a new relational reality. Listen:

11 For he who sanctifies and those who are sanctified all have one source. That is why he is not ashamed to call them brothers, 12 saying, “I will tell of your name to my brothers; in the midst of the congregation I will sing your praise.” 13 And again, “I will put my trust in him.” And again, “Behold, I and the children God has given me.”

We are now part of a pioneer family!

We are brothers and sisters of Jesus!

We have been set free!

And Jesus says, “Here am I, and the children God has given me.”

Why does it matter? It matters because it means you can stop grieving over the block of marble that has held you for so long and you can now start walking with the Pioneer of your salvation.

You were made for the pedestal, not for the prison.

Stop hugging the marble.

Stop white-knuckling the stone.

Stop fearing the journey.

Jesus, Savior, Lord, and King, has set you free.

In John 8:36 Jesus says, “So if the Son sets you free, you will be free indeed.”

Ah! Yes! Yes He does and yes we will be!

Come out of the prison. Become free in Jesus. Follow Him.

[1] https://www.accademia.org/explore-museum/halls/hall-prisoners/

[2] Guthrie, Donald. Hebrews (Tyndale New Testament Commentaries). InterVarsity Press. Kindle Edition.

[3] Osborne, Grant, Guthrie, George H.. Hebrews: Verse by Verse (p. 64). Lexham Press. Kindle Edition.

[4] Allen, David L. The Extent of the Atonement. (Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2016), p.581.