It is astonishing how aggressive the early church was in her missionary efforts. In his seminal work of 1792, An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens, William Carey marveled at the spread of the gospel in these early years. He writes:

It is astonishing how aggressive the early church was in her missionary efforts. In his seminal work of 1792, An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens, William Carey marveled at the spread of the gospel in these early years. He writes:

Peter speaks of a church at Babylon; Paul proposed a journey to Spain, and it is generally believed he went there, and likewise came to France and Britain. Andrew preached to the Scythians, north of the Black Sea. John is said to have preached in India, and we know that he was at the Isle of Patmos, in the Archipelago. Philip is reported to have preached in upper Asia, Scythia, and Phrygia; Bartholomew in India, on this side the Ganges, Phrygia, and Armenia; Matthew in Arabia, or Asiatic Ethiopia, and Parthia; Thomas in India, as far as the coast of Coromandel, and some say in the island of Ceylon; Simon, the Canaanite, in Egypt, Cyrene, Mauritania, Lybia, and other parts of Africa, and from thence to have come to Britain; and Jude is said to have been principally engaged in the lesser Asia, and Greece. Their labours were evidently very extensive, and very successful; so that Pliny, the younger, who lived soon after the death of the apostles, in a letter to the emperor, Trajan, observed that Christianity had spread, not only through towns and cities, but also through whole countries.[1]

Christianity Todayhas reported:

That Christianity reached China by the end of the first century has long been dismissed as a myth. Now, says the Chinese People’s Daily, evidence suggests it really happened. Wang Weifan from Jinling Seminary says tombstone carvings from about A.D.86 depict Bible stories and Christian designs.[2]

How astonishing. Christianity reached China by 86 AD? It is truly remarkable. Christianity from its beginning has been a missionary religion. For that reason, prayer support, logistical support, and financial support of missionaries has long been incumbent upon churches. Our covenant reflects this necessity:

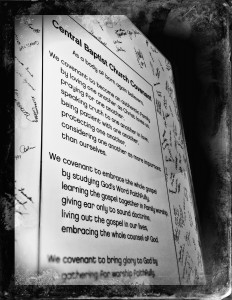

As a body of born again believers,

We covenant to become an authentic family by

loving one another as Christ loves us,

praying for one another,

speaking truth to one another in love,

being patient with one another,

protecting one another,

considering one another as more important than ourselves.

We covenant to embrace the whole gospel by

studying God’s Word faithfully,

learning the gospel together in family worship,

giving ear only to sound doctrine,

living out the gospel in our lives,

embracing the whole counsel of God.

We covenant to bring glory to God by

gathering for worship faithfully,

singing to the glory of God,

joining together in fervent prayer,

doing good works to the Father’s glory,

living lives that reflect the beauty of Christ,

giving offerings to God joyfully and faithfully.

We covenant to reach the nations by

sharing the gospel with those around us,

reaching out to the poor and the needy,

praying for the cause of missions in the world,

giving to the financial support of missions

On what basis do we justify the financial support of missions in the world?