I have got to be honest about something: I am not a big fan of Charles Dickens. I have tried. I am just not a big fan. However, I do love A Christmas Carol! What a great story! In particular, I love the way that A Christmas Carol begins. Do you remember? Listen:

Marley was dead: to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. The register of his burial was signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker, and the chief mourner. Scrooge signed it. And Scrooge’s name was good upon ‘Change, for anything he chose to put his hand to.

Old Marley was as dead as a door-nail.

Mind! I don’t mean to say that I know, of my own knowledge, what there is particularly dead about a door-nail. I might have been inclined, myself, to regard a coffin-nail as the deadest piece of ironmongery in the trade. But the wisdom of our ancestors is in the simile; and my unhallowed hands shall not disturb it, or the Country’s done for. You will therefore permit me to repeat, emphatically, that Marley was as dead as a door-nail.

Scrooge knew he was dead? Of course he did. How could it be otherwise?[1]

Well! One thing is clear: it was very important to Dickens that the reader understood that Jacob Marley, Ebenezer Scrooge’s former partner, was, in fact, dead. Why? Because in just a bit, Marley was going to visit Scrooge from beyond the grave! The certainty of Marley’s death lends force to the shock of Marley’s reappearance. Marley, of course, comes as a ghost. But Dickens needs the reader to understand: Marley really was dead.

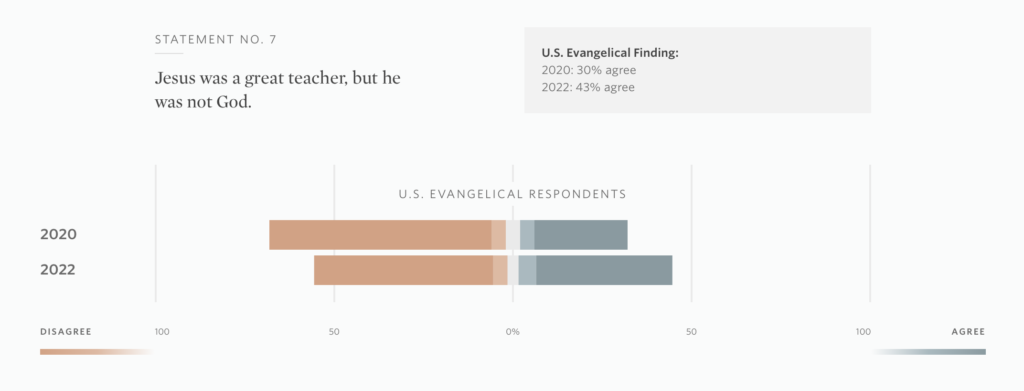

The Christian story hinges in part on the fact that the hero of our story, Jesus, really and truly and actually died on the cross. Here is how the Apostles’ Creed puts it: “was crucified, died, and was buried.” It is as if the writer/s of the Creed likewise needed us to understand this, because they use three images, all of which speak of death: (1) He was crucified. (2) He died. (3) He was buried.

Why this emphasis? Why this repetition? Because the shock of Jesus’ reappearance hinges on the certainty of His death. Jesus really died. And yet, to our amazement, there are some who have challenged even this idea. So let us consider carefully “was crucified, died, and was buried.”