Hebrews 1:1-3

1 Long ago, at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets, 2 but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son, whom he appointed the heir of all things, through whom also he created the world. 3 He is the radiance of the glory of God and the exact imprint of his nature, and he upholds the universe by the word of his power. After making purification for sins, he sat down at the right hand of the Majesty on high

In 2021 a (now “former”?) Christian musician shocked his many followers by tweeting the following:

Jesus was Christ.

Buddha was Christ.

Muhammad was Christ.

Christ is a word for the Universe seeing itself.

You are Christ.

We are the body of Christ.

In response to the many outraged comments of his fans, Gungor appealed to the influence of the liberal Franciscan Richard Rohr. Rohr, among other things, has drawn a distinction between “Jesus” and “Christ” and has argued that “Christ” cannot be reduced to and contained only in the historical figure of Jesus.[1] (I note that this distinction between “Jesus” and “Christ” is a favorite of theological liberals and takes many forms.) In Eliza Griswold’s New Yorker review of Rohr’s book The Universal Christ that so influenced Gungor and his tweet, she writes tellingly;

More conservative Christians tend to orient their theology around Jesus—his death and resurrection, which made salvation possible for those who believe. Rohr thinks that this focus is misplaced. The universe has existed for thirteen billion years; it couldn’t be, he argues, that God’s loving, salvific relationship with creation began only two thousand years ago, when the historical baby Jesus was placed in the musty hay of a manger, and that it only became widely knowable to humanity around six hundred years ago, when the printing press was invented and Bibles began being mass-produced. Instead, in his most recent book, “The Universal Christ,” which came out last year, Rohr argues that the spirit of Christ is not the same as the person of Jesus. Christ—essentially, God’s love for the world—has existed since the beginning of time, suffuses everything in creation, and has been present in all cultures and civilizations. Jesus is an incarnation of that spirit, and following him is our “best shortcut” to accessing it. But this spirit can also be found through the practices of other religions, like Buddhist meditation, or through communing with nature. Rohr has arrived at this conclusion through what he sees as an orthodox Franciscan reading of scripture. “This is not heresy, universalism, or a cheap version of Unitarianism,” he writes. “This is the Cosmic Christ, who always was, who became incarnate in time, and who is still being revealed.”

“All my big thoughts have coalesced into this,” he told me. “It’s my end-of-life book.” His message has been overwhelmingly well-received.[2]

The upshot of all of this is tragic. This attempt to dichotomize “Jesus” and “Christ” does great violence to the picture presented us in the scriptures. In the scriptures, Jesus is the Christ, the Son of the Living God and is not merely one manifestation of “Christ” among others. With all due respect to Rohr and Gungor et al. this is indeed heresy and it is indeed universalism. It diminishes Jesus and it guts the great Christian creed, “Jesus is Lord!”

If one were to look for the exact opposite approach to Jesus, one would need look no further than the book of Hebrews. This is a Jesus-entranced book. It is a beautiful book. And it elevates and exalts Jesus as Jesus the Christ, Jesus the Lord, Jesus the Son of God, and Jesus the only hope of the world!

The first three verses of the book are staggering. Ray Stedman writes, “The epistle to the Hebrews begins as dramatically as a rocket shot to the moon.”[3] I love it! Indeed it does! Let’s go…

There was a time back in the day when I gobbled up Philip Yancey books. I found them provocative and insightful.

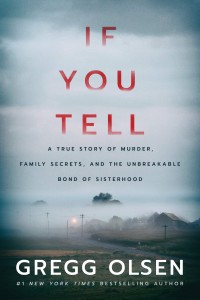

There was a time back in the day when I gobbled up Philip Yancey books. I found them provocative and insightful.  This will be a relatively brief review. I saw someone reference this book on Twitter (I believe) and decided to listen to the Audible version. It was equal parts enthralling and horrific…but more horrific than enthralling.

This will be a relatively brief review. I saw someone reference this book on Twitter (I believe) and decided to listen to the Audible version. It was equal parts enthralling and horrific…but more horrific than enthralling.