Haggai 2

Haggai 2

1In the seventh month, on the twenty-first day of the month, the word of the Lord came by the hand of Haggai the prophet: 2 “Speak now to Zerubbabel the son of Shealtiel, governor of Judah, and to Joshua the son of Jehozadak, the high priest, and to all the remnant of the people, and say, 3 ‘Who is left among you who saw this house in its former glory? How do you see it now? Is it not as nothing in your eyes? 4 Yet now be strong, O Zerubbabel, declares the Lord. Be strong, O Joshua, son of Jehozadak, the high priest. Be strong, all you people of the land, declares the Lord. Work, for I am with you, declares the Lord of hosts, 5 according to the covenant that I made with you when you came out of Egypt. My Spirit remains in your midst. Fear not.

I do so love these pictures that float around online that show people trying, and failing spectacularly, to create the item pictured on the package! Many of these are food-related. Here, for instance, is a cookie monster cupcake as presented and as attempted:

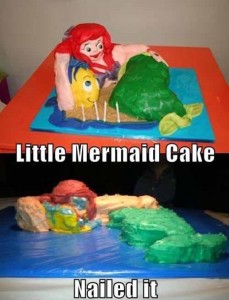

I love the sarcastic “Nailed it!” And here is a Little Mermaid cake:

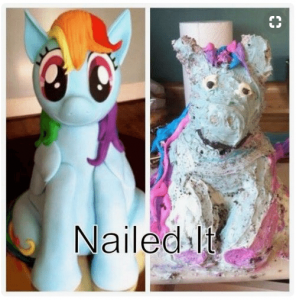

Whew! Not even close! And here is a bunny pancake and a pony cake:

But this one might be my favorite:

I laugh because pretty much anything I ever attempt runs into the same hilarious and frustrating problem.

There is a great distance between the “is” and the “ought,” no? We all know what it is to have our “Nailed it!” moment of disappointment. Israel did as well. Haggai 2 begins with Israel’s “Nailed it!” moment, their moment of sadness in the distance between the “is” and the “ought,” between the reality and expectation.

We must not be at peace with the distance between the “is” and the “ought.”

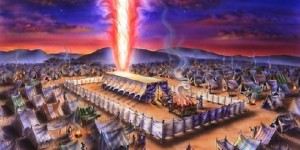

Israel heeded the call of God and returned to the task of rebuilding the temple. After a period of time, the Lord spoke to them about their work.

1 In the seventh month, on the twenty-first day of the month, the word of the Lord came by the hand of Haggai the prophet: 2 “Speak now to Zerubbabel the son of Shealtiel, governor of Judah, and to Joshua the son of Jehozadak, the high priest, and to all the remnant of the people, and say, 3 ‘Who is left among you who saw this house in its former glory? How do you see it now? Is it not as nothing in your eyes?

Carol and Eric Meyers point out that “this date is toward the end of Tishri—that is, on October 17, 520…nearly a month would have passed since the people responded to Haggai’s initial call to work.”[1]This is significant for, after a month, while the project was still certainly in its beginning stages, the people would have had time to get a sense of the scope of the project, of how it was going in its initial stages, and to begin to form opinions of how the work was progressing. For these reasons, the words of the Lord must have been devastating.

3 ‘Who is left among you who saw this house in its former glory? How do you see it now? Is it not as nothing in your eyes?

The note of disappointment is palpable. But why were those who remembered the former temple, the temple destroyed in 587 BC, disappointed? They were disappointed because they knew that this new temple would not be like the old. Verhoef explains:

The disappointment was…on account of the lack of suitable material and the absence of sacred objects, such as the ark of the covenant. The new temple, they realized, would never be like the old. They had no resources to pay skilled craftsmen from abroad as Solomon had done, and they could not begin to think of covering the interior with gold (1 K. 6:21, 22). In spite of the work already done, there was nothing to show for it.[2]

But there is something else. There is also the human tendency to romanticize the past. Ralph Smith makes the astute observation that “those who had seen the former temple would remember it through their eyes as children” and that “childhood memories of older adults are often fuzzy and sometimes exaggerated. These people might have remembered the former temple as greater and more splendid than it really was.” He concludes that this dynamic “could have added to their dejection when they saw the smallness of the new temple.”[3]

The interesting question is why God would point out the shabbiness of the current project in light of the temple’s former glory? Why would He do something that, in human terms and, perhaps, in modern terms, we would see as unduly critical and discouraging? I believe a couple of dynamics are at play here.

The first dynamic is that God did not want the people to grow accustomed to the distance between the “ought” and the “is,” between what the temple was in its state at that time and what it had been in its former glory. There is a human tendency to see “the perfect” as “the enemy of the good” and to grow accustomed to mediocrity since we can never be perfect. I believe that God is warning the people not to grow accustomed to mediocrity, not to settle. To do that, we must not be at peace with the distance between the “is” and the “ought.”

We can likely see this reality at play in Ezra 3 and the people’s reactions some years before when the foundation of the temple was initially laid after their return from exile. This is an uncomfortable passage. We would call it awkward. But watch the different reactions of the people.

10 And when the builders laid the foundation of the temple of the Lord, the priests in their vestments came forward with trumpets, and the Levites, the sons of Asaph, with cymbals, to praise the Lord, according to the directions of David king of Israel. 11 And they sang responsively, praising and giving thanks to the Lord, “For he is good, for his steadfast love endures forever toward Israel.” And all the people shouted with a great shout when they praised the Lord, because the foundation of the house of the Lord was laid. 12 But many of the priests and Levites and heads of fathers’ houses, old men who had seen the first house, wept with a loud voice when they saw the foundation of this house being laid, though many shouted aloud for joy, 13 so that the people could not distinguish the sound of the joyful shout from the sound of the people’s weeping, for the people shouted with a great shout, and the sound was heard far away.

Do you see? Many are thrilled at the laying of the foundation but those who knew what the temple used to begrieved at the distance between the “ought” and the “is.” It is good to lay the foundation! It is good to begin the work! But it is not enough. We must be driven by a desire to see the glory restored!

There is more happening here, as we will see, but I believe it is critically important for the modern church age to reclaim a sense of discontentment with the “is.” We must push toward the “ought.” We must not say, “Well I am a bit better than I was and I am certainly a lot better than that person!” No, we must desire to be more, to grow more, to look and sound ever more like Jesus Christ!

Have you grown dull in your efforts and content with mediocrity? Are you resting on your laurels, content with one step when there are a million more to go?

This will sound harsh in our day of “everybody gets a trophy.” It will sound too demanding. But Church, can we not look back at the glory of the early church and grieve that we do not have that kind of power, that kind of glory, that kind of influence, and that kind of world-transforming ministry? Is it not right for us to grieve at the distance between the “is” and the “ought.”

I do indeed celebrate small victories. We must! But we must never let the celebration of small victories cause us to lose our passion for bigger victories!

It is wonderful to see small victories…but let reach for great victories! Where there is progress, let us celebrate…but progress is not completion! Let us press on! Let us move forward!

But there is another reason why God raises the awkward point of the distance between their “is” and their “ought.” I believe He was not only trying to motivate the people to more, He was also trying to challenge the people not to despair!

But neither should we despair, for between the “is” and the “ought” is God’s gift of the “becoming.”

What the Lord says immediately after pointing out their limited success is crucially important.

4 Yet now be strong, O Zerubbabel, declares the Lord. Be strong, O Joshua, son of Jehozadak, the high priest. Be strong, all you people of the land, declares the Lord. Work, for I am with you, declares the Lord of hosts, 5 according to the covenant that I made with you when you came out of Egypt. My Spirit remains in your midst. Fear not.

“Yet now be strong.”

It is as if the Lord is saying, “I know how discouraging the distance between the ‘is’ and the ‘ought’ can be for you, especially to those of you who remember the temple in its former glory! But do not despair! Do not grieve yourself into inactivity! Be strong! I am with you! The glory will return! I am with you in the process of becoming!”

As a pastor, I have seen this dynamic in the local church. I once pastored a church in which a certain group of people seemed to be stuck in the past. They would speak of large youth trips that their large youth group took twenty years before, of large choirs that filled their choir loft years before. Their fixation on what waswas obvious. I wanted, at times, to yell aloud, “But what about now! What about the kids in the youth group now! What about our choir now! This is their moment! This is their time! Do not miss the beauty of the present because of constant comparison to the past. Join us in the journey of becoming instead of getting stuck in the story of what was.”

True, we must not become content with the “is,” but neither should it cause us to despair. This is why God moves on in our text to call the people to hope and to renewed effort.

Our text truly is an important text for congregations today.

To the young, the Lord says, “Do not grow content with comfortable mediocrity.”

To the old, the Lord says, “Do not get stuck in your memories of the past.”

To old and young alike the Lord says, “I am still here! I am right here! Get up! Get to work! Be strong! The God who brought glory in the old days is the God who is with you right now! I am here!”

Observe the empowerment of God and the obedience of man: “Work, for I am with you.”

We do not work in our own strength, but we do work.

We do not trust in our own obedience, but we do obey.

And as this happens, God’s gift of “becoming” happens. We begin to become what we ought to be. We begin to grow, to change, to move forward!

Christ never leaves His people in the “is.” He always moves in and through and among us to help us become what we ought. And the posture we must embrace in this becoming is therefore a posture of expectancy, a posture of hope, a posture of readiness.

“Fear not,” the Lord told Israel. There is more happening than what you see!

God is with us!

God is at work in and through us!

Let us work in the light of that promise!

[1]Carol L. Meyers and Eric M. Meyers, Haggai, Zechariah 1-8. The Anchor Bible. (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1987), p.49.

[2]Pieter A. Verhoef, The Books of Haggai and Malachi.The New International Commentary on the Old Testament. (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1987), p.97.

[3]Ralph L. Smith, Micah-Malachi. Word Biblical Commentary. vol.32 (Waco, TX: Word Books, Publishers, 1984), p.157.

Exodus 40

Exodus 40

Haggai 2

Haggai 2 Exodus 36

Exodus 36

Brandon O’Brien’s

Brandon O’Brien’s  Exodus 35

Exodus 35