The next number of posts in the Patristic Summaries Series will concern what is known as “The Seven Ecumenical Councils” of the Church. In writing these posts, I am consulting (a) historical insights from Leo Donald Davis’ The First Seven Ecumenical Councils: Their History and Theology and Peter L’Huillier’s The Church of the Ancient Councils: The Disciplinary Work of the First Four Ecumenical Councils and (b) the primary sources surrounding each council (to the extent that we have them) in volume 14 of the post-nicene writings of Philip Schaff and Henry Wace’s (editors) 38 volume Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers (Second Series).

The next number of posts in the Patristic Summaries Series will concern what is known as “The Seven Ecumenical Councils” of the Church. In writing these posts, I am consulting (a) historical insights from Leo Donald Davis’ The First Seven Ecumenical Councils: Their History and Theology and Peter L’Huillier’s The Church of the Ancient Councils: The Disciplinary Work of the First Four Ecumenical Councils and (b) the primary sources surrounding each council (to the extent that we have them) in volume 14 of the post-nicene writings of Philip Schaff and Henry Wace’s (editors) 38 volume Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers (Second Series).

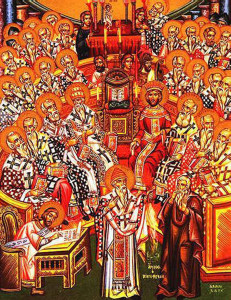

The Emperor Constantine convened the first great ecumenical council in 325 AD primarily to address the Arian attack on the full deity of Christ, though the council addressed many other issues as well. The most significant contribution of the council was, of course, the Nicene Creed.

I believe in one God,

the Father Almighty,

maker of heaven and earth,

and of all things visible and invisible;

And in one Lord Jesus Christ,

the only begotten Son of God,

begotten of his Father before all worlds,

God of God, Light of Light,

very God of very God,

begotten, not made,

being of one substance with the Father;

by whom all things were made;

who for us men and for our salvation

came down from heaven,

and was incarnate by the Holy Ghost

of the Virgin Mary,

and was made man;

and was crucified also for us under Pontius Pilate;

he suffered and was buried;

and the third day he rose again

according to the Scriptures,

and ascended into heaven,

and sitteth on the right hand of the Father;

and he shall come again, with glory,

to judge both the quick and the dead;

whose kingdom shall have no end.

And I believe in the Holy Ghost the Lord, and Giver of Life,

who proceedeth from the Father [and the Son];

who with the Father and the Son together

is worshipped and glorified;

who spake by the Prophets.

And I believe one holy Catholic and Apostolic Church;

I acknowledge one baptism for the remission of sins;

and I look for the resurrection of the dead,

and the life of the world to come. AMEN.

Along with The Apostles’ Creed, The Nicene Creed is acknowledged to be one of the most substantive, concise, beautiful, and theologically rich statements on the essence of Chrisitianity ever written. The creed was adopted with very little opposition and it should be rightly hailed as the seminal achievement of the Council of Nicaea.

Baptists are traditionally considered to be anti-creedal. This is an oversimplification to be sure. While Baptists unapologetically hold to the Reformation maxim sola scripture, we really mean by it suprema scripture. That is, Baptists have never held that all creedal statements are utterly useless and wholly flawed. On the contrary, Baptists have simply asserted that the witness of Scripture outweighs all other statements of man, no matter how revered, and should be granted preeminence and supremacy. In point of fact, the 38th article of the 1679 General Baptist “Orthodox Creed” commends the Apostles’, Nicene, and Athanasian creeds to all Baptists as valuable and worthy of study and consideration.

The subtle but profound debates surrounding the terminology of the creed, particularly pertaining to Christology, are important but go far beyond the nature of these patristic summaries. Suffice it to say, the language of the creed is in no way accidental. Rather, it communicates biblical orthodoxy as agreed upon by conciliar consensus and establishes an orthodox line of demarcation against all inferior Christological assertions.

In addition to the creed, the Council of Nicaea approved a number of canons addressing various and sundry realities facing the church at that time. For instance, the canons forbade those who mutilated themselves from holding ecclesial office, addressed the question of how the church should receive back repentant schismatic bishops, condemned usury, forbade the clergy from taking women disciples into their homes, addressed the issue of deaconesses, etc. These canons are fascinating and insightful, and are still essentially binding to large segments of Christianity today.

The Council of Nicaea has been the subject of a great deal of misunderstanding. On the popular level this is undoubtedly due to Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code nonsense. Wherever these misunderstands originate, it is almost a given today among those who have never studied what happened at Nicaea that the council was convened by a sinister Emperor who arbitrarily and almost single-handedly defined orthodoxy over against earlier and more appealing orthodoxies within early Christianity, that he used a structure of power to establish further structures of power in order to subjugate the people to oppressive systems of belief he himself proclaimed true and binding, and that Constantine chose at the Council which books would be included in the canon of scripture editing out those texts that challenged the increasingly narrow orthodoxy of institutional Christianity. This last allegation is simply inexplicable since the Council said nothing about the canon of scripture in terms of what books should be included therein. These readings of the Council are borne from ignorance at best and a modernistic agenda at worst.

That is not to say that the Council was perfect or infallible or devoid of politics or anything of the sort. I am no apologist for any pronouncements of any gathering of Christians, no matter how august that gather might be. Rather, it is simply to say that the Council articulated a vision of orthodoxy that has struck the vast majority of the Church as biblical and God-honoring and true for the vast majority of her history. Baptist Christians should study the results of Nicaea with great appreciation and interest. They will, however, along with many other believers, judge the fruits of even this amazing assembly by holy writ.