I’m going to post this as simply a point of interest, though one I am very much still thinking through. For some time I have heard conversations similar to this come up among pastors. My only opinions at the moment are (a) that there likely needs to be a definitive break between the church and secular society on the question of marriage and (b) that such a break would indeed raise a number of difficult questions about how the church views marriage and, in particular, divorce that the church would really have to think through. My interest in this is convictional: I simply do believe that what the state says about marriage and what the church says about marriage are two very separate things except insofar as they conveniently overlap. The recent social experiments are causing the church today to think through the lines of demarcation, and I think, on the whole, that is a positive thing. More on these later, but, for now, check out Olson’s first post and then his second clarifying post.

Category Archives: Uncategorized

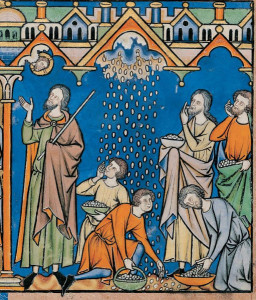

Exodus 16

1 They set out from Elim, and all the congregation of the people of Israel came to the wilderness of Sin, which is between Elim and Sinai, on the fifteenth day of the second month after they had departed from the land of Egypt. 2 And the whole congregation of the people of Israel grumbled against Moses and Aaron in the wilderness, 3 and the people of Israel said to them, “Would that we had died by the hand of the Lord in the land of Egypt, when we sat by the meat pots and ate bread to the full, for you have brought us out into this wilderness to kill this whole assembly with hunger.” 4 Then the Lord said to Moses, “Behold, I am about to rain bread from heaven for you, and the people shall go out and gather a day’s portion every day, that I may test them, whether they will walk in my law or not. 5 On the sixth day, when they prepare what they bring in, it will be twice as much as they gather daily.” 6 So Moses and Aaron said to all the people of Israel, “At evening you shall know that it was the Lord who brought you out of the land of Egypt, 7 and in the morning you shall see the glory of the Lord, because he has heard your grumbling against the Lord. For what are we, that you grumble against us?” 8 And Moses said, “When the Lord gives you in the evening meat to eat and in the morning bread to the full, because the Lord has heard your grumbling that you grumble against him—what are we? Your grumbling is not against us but against the Lord.” 9 Then Moses said to Aaron, “Say to the whole congregation of the people of Israel, ‘Come near before the Lord, for he has heard your grumbling.’” 10 And as soon as Aaron spoke to the whole congregation of the people of Israel, they looked toward the wilderness, and behold, the glory of the Lord appeared in the cloud. 11 And the Lord said to Moses, 12 “I have heard the grumbling of the people of Israel. Say to them, ‘At twilight you shall eat meat, and in the morning you shall be filled with bread. Then you shall know that I am the Lord your God.’” 13 In the evening quail came up and covered the camp, and in the morning dew lay around the camp. 14 And when the dew had gone up, there was on the face of the wilderness a fine, flake-like thing, fine as frost on the ground. 15 When the people of Israel saw it, they said to one another, “What is it?” For they did not know what it was. And Moses said to them, “It is the bread that the Lord has given you to eat. 16 This is what the Lord has commanded: ‘Gather of it, each one of you, as much as he can eat. You shall each take an omer, according to the number of the persons that each of you has in his tent.’” 17 And the people of Israel did so. They gathered, some more, some less. 18 But when they measured it with an omer, whoever gathered much had nothing left over, and whoever gathered little had no lack. Each of them gathered as much as he could eat. 19 And Moses said to them, “Let no one leave any of it over till the morning.” 20 But they did not listen to Moses. Some left part of it till the morning, and it bred worms and stank. And Moses was angry with them. 21 Morning by morning they gathered it, each as much as he could eat; but when the sun grew hot, it melted. 22 On the sixth day they gathered twice as much bread, two omers each. And when all the leaders of the congregation came and told Moses, 23 he said to them, “This is what the Lord has commanded: ‘Tomorrow is a day of solemn rest, a holy Sabbath to the Lord; bake what you will bake and boil what you will boil, and all that is left over lay aside to be kept till the morning.’” 24 So they laid it aside till the morning, as Moses commanded them, and it did not stink, and there were no worms in it. 25 Moses said, “Eat it today, for today is a Sabbath to the Lord; today you will not find it in the field. 26 Six days you shall gather it, but on the seventh day, which is a Sabbath, there will be none.” 27 On the seventh day some of the people went out to gather, but they found none. 28 And the Lord said to Moses, “How long will you refuse to keep my commandments and my laws? 29 See! The Lord has given you the Sabbath; therefore on the sixth day he gives you bread for two days. Remain each of you in his place; let no one go out of his place on the seventh day.” 30 So the people rested on the seventh day. 31 Now the house of Israel called its name manna. It was like coriander seed, white, and the taste of it was like wafers made with honey. 32 Moses said, “This is what the Lord has commanded: ‘Let an omer of it be kept throughout your generations, so that they may see the bread with which I fed you in the wilderness, when I brought you out of the land of Egypt.’” 33 And Moses said to Aaron, “Take a jar, and put an omer of manna in it, and place it before the Lord to be kept throughout your generations.” 34 As the Lord commanded Moses, so Aaron placed it before the testimony to be kept. 35 The people of Israel ate the manna forty years, till they came to a habitable land. They ate the manna till they came to the border of the land of Canaan. 36 (An omer is the tenth part of an ephah.)

The miracle of the fish at Valley Forge in the winter of 1778 is a disputed tale of an allegedly miraculous catch of shad in the Schuylkill River. In her article, “Starving Soldiers at Valley Forge,” written for The History Channel, Stephanie Butler offers a nice summary.

In December of 1778, the Continental Army was retreating in the face of a British advance on Philadelphia, but they also needed a place, as Armies did back then, to make winter quarters.

The Army’s commanding general, George Washington, chose a spot on the Schuylkill River called Valley Forge…Pennsylvania winters are harsh and the army was tired. They had neither winter clothing nor a regular supply of food. Most of the soldiers lived on near starvation rations.

When Washington arrived at Valley Forge, just days before Christmas, his army numbered about 10,000 and his situation was desperate…There was heavy snow Christmas Day and since they still were working on building cabins, most of the men still were in tents. They hadn’t been paid, didn’t have enough food, and many had no shoes, but Washington did his best to see the men had some kind of Christmas.

He hosted a somewhat meager dinner for his officers, and then saw to it that each soldier had an allotment of rum and something to eat. Both the general and Mrs. Washington did their best to visit each encampment.

It also was at Valley Forge that Washington is said, on Christmas Day, to have ridden into the woods to pray. It’s presumed the general prayed for strength and guidance, but no one really knows. Besides, what he prayed about is his business, but his need to find some time to be alone and to talk to God suggests the spiritual side of this remarkable individual. It also could be argued, given what followed, that God was giving a little extra attention to the Washington’s prayers.

Amazingly — and this was recorded by several of the foreign officers, including the Marquis De Lafayette — the morale of the Continental Army at Christmastime revived. Even without adequate rations and amid appalling living conditions, the men sang, told stories, and enjoyed their Christmas.

There also was, a few weeks later, an early running of the shad. It was far too early for this protein rich fish to make its appearance, but for many soldiers, freezing and near starvation, it was nothing short of a miracle. The work of the Army continued too. Even in the snow, under the direction of Baron Von Steuben, a former Prussian officer, the Continental Army remade itself.[1]

Should we believe such a story? Who knows? Regardless, it would appear that something happened that was (a) quite unusual and (b) was regarded as a miracle by many who were there. I rather suspect the story is true. It would not, after all, be the first time that God miraculously fed a starving people.

Exodus 16 is a chapter that records a much earlier feeding miracle, and one on a grand scale at that! Here we find the miraculous feeding of the children of Israel in the wilderness with quail and manna. This astounding occurrence says a great deal about God, of course, but it also reveals a great deal about us.

God is faithful to provide for His people.

The most obvious point of Exodus 16 is that God is faithful to provide for His people. If God’s deliverance through the Red Sea was not sufficient enough evidence, and if His miraculous changing of the bitter waters of Marah did not put an end to their doubts, then God’s actions in this chapter certainly should have…or at least we would have thought. Notice the providing hand of God.

4 Then the Lord said to Moses, “Behold, I am about to rain bread from heaven for you, and the people shall go out and gather a day’s portion every day, that I may test them, whether they will walk in my law or not. 5 On the sixth day, when they prepare what they bring in, it will be twice as much as they gather daily.” 6 So Moses and Aaron said to all the people of Israel, “At evening you shall know that it was the Lord who brought you out of the land of Egypt, 7 and in the morning you shall see the glory of the Lord, because he has heard your grumbling against the Lord. For what are we, that you grumble against us?”

13 In the evening quail came up and covered the camp, and in the morning dew lay around the camp. 14 And when the dew had gone up, there was on the face of the wilderness a fine, flake-like thing, fine as frost on the ground.

First we see the promise then we see the fulfillment. God sends quail and manna. As with virtually every miracle in the Bible, many have proposed a naturalistic explanation. Thus, Terence Fretheim has pointed out that the Bible’s description of manna “corresponds quite closely to a natural phenomenon in the Sinai Peninsula.” He explains:

A type of plant lice punctures the fruit of the tamarisk tree and excretes a substance from this juice, a yellowish-white flake or ball. During the warmth of the day it disintegrates, but it congeals when it is cold. It has a sweet taste. Rich in carbohydrates and sugar, it is still gathered by natives, who bake it into a kind of bread (and call it manna). The food decays quickly and attracts ants. Regarding the quails, migratory birds flying in from Africa or blown in from the Mediterranean are often exhausted enough to be caught by hand.[2]

The insight about quail getting tired seems absurd, and the insight about manna seems plausible to an extent. Regardless, if both of these natural explanations play a part, they only play a part in the sense that God took natural phenomenon and miraculously bent them toward His own will. Of course, this is what God does all of the time when He acts in miraculous ways. Consider the feeding of the five thousand. That miracle involved “natural” phenomenon: bread and fish (though bread, of course, has to be made). But Jesus took bread and fish and multiplied it miraculously.

If God used the excretions of plant lice and the exhaustion of migrating quail to fulfill his promise of provision, it was no less miraculous. Just think of it: for forty years God had the little plant lice secrete enough substance to provide manna every morning for hundreds of thousands of Israelites. And if God caused the quail to grow exhausted just over where the Israelites were encamped, he did so every evening for forty years.

Regardless, these questions of how are not as significant as the reality that God did in fact provide! Here we see an astonishing and faithful fulfillment of that which Jesus taught us to pray: “Give us this day our daily bread” (Matthew 6:11).

Our God is a providing God.

God’s provisions cannot be increased by human greed or diminished by human despair.

He is a providing God, and His provisions can neither be increased by human greed nor diminished by human despair. Predictably, many of the Israelites wanted more than what was provided. The results were disastrous as God had foretold.

17 And the people of Israel did so. They gathered, some more, some less. 18 But when they measured it with an omer, whoever gathered much had nothing left over, and whoever gathered little had no lack. Each of them gathered as much as he could eat. 19 And Moses said to them, “Let no one leave any of it over till the morning.” 20 But they did not listen to Moses. Some left part of it till the morning, and it bred worms and stank. And Moses was angry with them.

25 Moses said, “Eat it today, for today is a Sabbath to the Lord; today you will not find it in the field. 26 Six days you shall gather it, but on the seventh day, which is a Sabbath, there will be none.” 27 On the seventh day some of the people went out to gather, but they found none. 28 And the Lord said to Moses, “How long will you refuse to keep my commandments and my laws?

Those who gathered more manna than they needed and those who set out on the Sabbath looking for more than they already had been provided with were both justly rebuked. Here is a powerful principle that we had best come to terms with: God provides enough. Greed and despair warp our perspectives of His character or, maybe more accurately, reveal that we have a perspective that has been warped.

I have recently been reading the canons of the Council of Nicaea from 325 A.D. The seventeenth canon states:

Forasmuch as many enrolled among the Clergy, following covetousness and lust of gain, have forgotten the divine Scripture, which says, “He hath not given his money upon usury,” and in lending money ask the hundredth of the sum, the holy and great Synod thinks it just that if after this decree any one be found to receive usury, whether he accomplish it by secret transaction or otherwise, as by demanding the whole and one half, or by using any other contrivance whatever for filthy lucre’s sake, he shall be deposed from the clergy and his name stricken from the list.[3]

This means that the church of the 4th century forbade loaning money on interest. My purpose is not to discuss the ethics of interest. My point is simply to say that here at the first ecumenical council of the Church they had to condemn the clergy fleecing the people for more money than they needed. It is but one example of countless examples of greed, of failing to trust God as we should for His provision.

It is fascinating that God builds safeguards against both greed and despair in this wilderness arrangement for food: there will be enough.

What would it be like if we reached the point where we thought God had given us enough?

God’s provisions tend not to be appreciated as they should by His people.

One of the recurring themes of Israel’s wilderness wonderings is the theme of failing to appreciate God’s gracious provisions. Note the repetitious use of the image of grumbling.

2 And the whole congregation of the people of Israel grumbled against Moses and Aaron in the wilderness, 3 and the people of Israel said to them, “Would that we had died by the hand of the Lord in the land of Egypt, when we sat by the meat pots and ate bread to the full, for you have brought us out into this wilderness to kill this whole assembly with hunger.”

Peter Enns says of this charge, “Only the most calloused heart or the most stupid mind could conceive of such a ridiculous charge.”[4] That is blunt, but true. After God’s great provision and miraculous deliverance of His children from Egypt and at the waters of Marah, they still grumbled and complained. Even in Moses’ revelation that God would send food to the Israelites he indicted them for their absurd grumbling.

6 So Moses and Aaron said to all the people of Israel, “At evening you shall know that it was the Lord who brought you out of the land of Egypt, 7 and in the morning you shall see the glory of the Lord, because he has heard your grumbling against the Lord. For what are we, that you grumble against us?” 8 And Moses said, “When the Lord gives you in the evening meat to eat and in the morning bread to the full, because the Lord has heard your grumbling that you grumble against him—what are we? Your grumbling is not against us but against the Lord.”

The Lord likewise notes their complaining spirit.

11 And the Lord said to Moses, 12 “I have heard the grumbling of the people of Israel.

Our grumbling says a great deal about us and how we see the world. Victor Hamilton has made an interesting observation about the nature of the grumbling mind-set.

The Israelites’ mind-set is not unlike that of criminals released from incarceration. Imprisonment, but with three meals a day and a place to lay one’s head at night, seems more inviting than struggling with the challenges of liberty. Being told what to do and when to do it and how to do it may be easier than having to make one’s own (responsible) decisions. In a strange way Egypt can become Eden. A ghetto can become a garden, or so it seems. Pharaoh can become a “nice guy,” a life-giver, while Moses can become a villain, a life-taker.[5]

A refusal to trust leads to a complaining spirit that, in terms, hinders us from actually seeing reality for what it is. This is the story of the human race. Indeed, there is ample evidence in scripture to suggest that most people simply do not take the time to thank God for the provisions He does indeed supply. We can see this in Luke 17, for instance, in Jesus’ healing of the ten lepers.

11 On the way to Jerusalem he was passing along between Samaria and Galilee. 12 And as he entered a village, he was met by ten lepers, who stood at a distance 13 and lifted up their voices, saying, “Jesus, Master, have mercy on us.” 14 When he saw them he said to them, “Go and show yourselves to the priests.” And as they went they were cleansed. 15 Then one of them, when he saw that he was healed, turned back, praising God with a loud voice; 16 and he fell on his face at Jesus’ feet, giving him thanks. Now he was a Samaritan. 17 Then Jesus answered, “Were not ten cleansed? Where are the nine? 18 Was no one found to return and give praise to God except this foreigner?” 19 And he said to him, “Rise and go your way; your faith has made you well.”

Dear church, do not allow grumbling to overtake your minds and hearts. When is the last time you stopped and said, “Thank you, God, for providing for me”?

God’s provisions should lead to rest and worship.

And what is the ultimate purpose of God’s provision? Holy rest. Sabbath rest. Praise.

The Lord provides. His people gather. Then we should rest. We find one of the clearest articulations of the need for Sabbath rest in our text.

22 On the sixth day they gathered twice as much bread, two omers each. And when all the leaders of the congregation came and told Moses, 23 he said to them, “This is what the Lord has commanded: ‘Tomorrow is a day of solemn rest, a holy Sabbath to the Lord; bake what you will bake and boil what you will boil, and all that is left over lay aside to be kept till the morning.’” 24 So they laid it aside till the morning, as Moses commanded them, and it did not stink, and there were no worms in it. 25 Moses said, “Eat it today, for today is a Sabbath to the Lord; today you will not find it in the field. 26 Six days you shall gather it, but on the seventh day, which is a Sabbath, there will be none.” 27 On the seventh day some of the people went out to gather, but they found none. 28 And the Lord said to Moses, “How long will you refuse to keep my commandments and my laws? 29 See! The Lord has given you the Sabbath; therefore on the sixth day he gives you bread for two days. Remain each of you in his place; let no one go out of his place on the seventh day.” 30 So the people rested on the seventh day.

Peter Enns rightly observes, “It is not simply that the Sabbath is ‘observed’ by the Israelites in that they refrain from gathering food. Rather, it is God who refrains from supplying the food. It is he who ceases working, so that no manna or quail is to be founded.”[6] This is consistent with the Genesis account of creation. In Genesis 2 we read:

2 By the seventh day God had finished the work he had been doing; so on the seventh day he rested from all his work. 3 Then God blessed the seventh day and made it holy, because on it he rested from all the work of creating that he had done.

There is an absurd notion in our country, perhaps mainly among men (it seems to me), that excessive, self-destructive busyness ostensibly in the name of providing for our families is a virtue to be celebrated. In fact it is a vice to be deplored. I am aware of the fact that at times and seasons of life and in certain circumstances people simply must work more than they should. Again, I understand this. I am talking here, though, about the modern penchant for unnecessary busyness. It is largely unnecessary because it is embraced in order to fund things we simply do not need in many cases. We thereby shortchange our children and our spouses by being busier than we need to be.

In the process, we lose the very idea and logic of Sabbath rest. We fail to rest because we do not take seriously God’s absolute seriousness about the Sabbath rhythm of life: work for six days and rest on the seventh.

We are especially adept at pointing out absurd legalisms concerning Sabbath observance, and there can be no denying that the Church has sometimes fallen into such legalisms to the same extent that many Pharisees did. However, the problem in most churches today is not legalism concerning the Sabbath but crude license concerning it. That is, we barely observe it at all, it seems to me. Please note, however, that as God led His children through the wilderness He insisted on Sabbath rest.

How do we best give praise to God for His provisions? Surely not by frantically grasping for more than we need. No, we best give praise by observing Sabbath rest and worship to the glory of His great name.

God provides. He does so in astounding and beautiful ways. Open your eyes to the manna He gives us every day. Work to gather then stop to rest. Through all, praise His great name!

[1] https://www.history.com/news/hungry-history/starving-soldiers-at-valley-forge

[2] Terence Fretheim, Exodus. Interpretation. (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), p.182.

[3] https://www.christian-history.org/council-of-nicea-canons.html#17

[4] Peter Enns, Exodus. The NIV Application Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2000), p.324.

[5] Hamilton, Victor P. (2011-11-01). Exodus: An Exegetical Commentary (Kindle Locations 8426-8429). Baker Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

[6] Peter Enns, p.325.

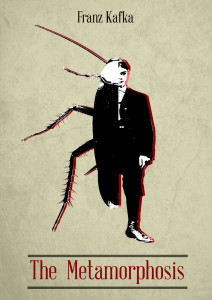

Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis

Franz Kafka’s famous short story, “The Metamorphosis,” is an enigmatic and elusive tale about a salesman named Gregor Samsa who awakens one morning to find that he has been changed into a bug. I should say instead that the tale is elusive in terms of its interpretation. The story itself, on its surface, is rather straightforward.

Franz Kafka’s famous short story, “The Metamorphosis,” is an enigmatic and elusive tale about a salesman named Gregor Samsa who awakens one morning to find that he has been changed into a bug. I should say instead that the tale is elusive in terms of its interpretation. The story itself, on its surface, is rather straightforward.

Samsa wakes up to find that he is a bug. His parents and his sister (all of whom he provides for and the last whom he adores) knock on the door in vain, as does a representative from his job who comes by to chastise him. When they finally see Gregor, they are terrified and disgusted. The remainder of the story involves the family’s failed attempts to come to terms with Gregor’s metamorphosis. The most compassionate is his sister, Greta, who feeds Gregor by leaving food in his room while he hides under a couch. Eventually, however, she too proclaims her disgust with Gregor and he dies brokenhearted.

What makes the story so intriguing is that it really does not tip its hand too much to possible meanings. Some have seen it as Kafka’s story about his own self (notice the consistent consonant/vowel structure of the names: Kafka – Samsa) and his sense of alienation from the world. Others have surmised that it might be a statement on the dehumanizing and eventual destruction of the Jews (as represented by Gregor).

It’s hard to say, though I find myself drawn to a something like a class-structure interpretation. Maybe. It seems to me that Gregor, the worker, is dehumanized, is shown a measure of pity by those who cannot understand him, and is eventually abandoned by those with brighter prospects. I am struck by the last sentence, which sees Greta stretching her blossoming body out after her parents, taking notice, reflect on the fact that they need to find her a suitable mate: “And it was like a confirmation of their new dreams and excellent intentions that at the end of their journey their daughter sprang to her feet and stretched her young body.” Thus, the book begins with a downward metamorphoses: that of a man into a bug. It ends with an upward metamorphosis: that of a girl into a beautiful young woman. The downward metamorphosis ends in dehumanization, a loss of meaning and significance, and then a death that is welcomed by the others who were so burdened by his grotesque existence. The upward metamorphoses ends in a humanization, the opening of prospects and a bright future, and a general sense of celebration by others who witness it.

On the other hand, I am struck by the note of existential despair in the story, Gregor’s horror at realizing that his very existence is a burden, that his presence is loathsome to those around him, and the utter futility of his life theretofore. Who hasn’t at time felt a bit like Gregor: alone, misunderstood, barely human?

It is a powerful little tale, and one that stays with you. I suppose the brilliance of it is that different readers can see different aspects of their own lives in the tragedy of Gregor Samsa. If you haven’t read it, you should. It’s compelling, troubling, thought-provoking, and significant.

Ruth 4:1-12

1 Now Boaz had gone up to the gate and sat down there. And behold, the redeemer, of whom Boaz had spoken, came by. So Boaz said, “Turn aside, friend; sit down here.” And he turned aside and sat down. 2 And he took ten men of the elders of the city and said, “Sit down here.” So they sat down. 3 Then he said to the redeemer, “Naomi, who has come back from the country of Moab, is selling the parcel of land that belonged to our relative Elimelech. 4 So I thought I would tell you of it and say, ‘Buy it in the presence of those sitting here and in the presence of the elders of my people.’ If you will redeem it, redeem it. But if you will not, tell me, that I may know, for there is no one besides you to redeem it, and I come after you.” And he said, “I will redeem it.” 5 Then Boaz said, “The day you buy the field from the hand of Naomi, you also acquire Ruth the Moabite, the widow of the dead, in order to perpetuate the name of the dead in his inheritance.” 6 Then the redeemer said, “I cannot redeem it for myself, lest I impair my own inheritance. Take my right of redemption yourself, for I cannot redeem it.” 7 Now this was the custom in former times in Israel concerning redeeming and exchanging: to confirm a transaction, the one drew off his sandal and gave it to the other, and this was the manner of attesting in Israel. 8 So when the redeemer said to Boaz, “Buy it for yourself,” he drew off his sandal. 9 Then Boaz said to the elders and all the people, “You are witnesses this day that I have bought from the hand of Naomi all that belonged to Elimelech and all that belonged to Chilion and to Mahlon. 10 Also Ruth the Moabite, the widow of Mahlon, I have bought to be my wife, to perpetuate the name of the dead in his inheritance, that the name of the dead may not be cut off from among his brothers and from the gate of his native place. You are witnesses this day.” 11 Then all the people who were at the gate and the elders said, “We are witnesses. May the Lord make the woman, who is coming into your house, like Rachel and Leah, who together built up the house of Israel. May you act worthily in Ephrathah and be renowned in Bethlehem, 12 and may your house be like the house of Perez, whom Tamar bore to Judah, because of the offspring that the Lord will give you by this young woman.”

It is fitting that we are approaching the Lord’s Supper table on this day when we also approach Ruth 4:1-12. That is because these verses speak of a bridegroom’s redemption of his bride. That is also exactly what the Lord’s Supper speaks of as well: a Bridegroom’s redemption of His bride. As I hope to show, this text is where the bottom level story (the actual story of Boaz and Ruth) and the upper level story (the story of Christ and His Church) come closest to one another. As we read this text in preparation for the Lord’s Supper, I would like to consider the fact that Boaz’s purchase of his bride, Ruth, was eager, public, and legally binding. So is Jesus’ purchase of His bride.

Eager. Public. Legally binding.

Eager. Boaz was eager to secure Ruth as his bride.

1 Now Boaz had gone up to the gate and sat down there. And behold, the redeemer, of whom Boaz had spoken, came by. So Boaz said, “Turn aside, friend; sit down here.” And he turned aside and sat down.

Chapter 3 ended with the startling events on the threshing floor that saw Ruth pledge herself to Boaz and Boaz assure her that he would redeem and marry her if at all possible. There was one problem: there was a relative closer to Naomi and Ruth than Boaz was and, by law, that relative was given the first option of redemption. Boaz would only be able to redeem Ruth if this other relative chose not to.

Our chapter begins with Boaz eagerly seeking to redeem Ruth. He went to the place where such business was handled: the city gates. And when did he go? The next morning, the morning after Ruth came to him and lay at his feet on the threshing floor. The night before Boaz had said to Ruth, “Stay here for the night, and in the morning if he wants to do his duty as your guardian-redeemer, good; let him redeem you. But if he is not willing, as surely as the Lord lives I will do it. Lie here until morning” (v.13). Twice he mentioned the morning. He was eager for Ruth to be his bride. He would handle this as soon as humanly possible. Even Naomi knew that he would be eager to resolve this, for in verse 18 of Ruth 3 she had told Ruth, “Wait, my daughter, until you find out what happens. For the man will not rest until the matter is settled today.” And indeed he did not.

The redeemer was eager to redeem the one needing redemption. So it was with Boaz and Ruth. So it is with Jesus. In Luke 15:20 Jesus likened God to a patriarch who runs and embraces his prodigal son when he returns home. Eagerness. In 2 Peter 3:9, Peter writes, “The Lord is not slow to fulfill his promise as some count slowness, but is patient toward you, not wishing that any should perish, but that all should reach repentance.” The Father is eager to see people come to faith in Christ. He is, in fact, eager to see you come to the saving knowledge of Christ if you have not.

Boaz summoned the closer redeemer. Interestingly, he did not use his name. Some early Jewish commentators assumed the man’s name was Tob because of verse 3:13. In that verse, Boaz said to Ruth, “Remain tonight, and in the morning, if he will redeem you, good; let him do it.” The Hebrew word for “good” or “all right” is “tob,” so these commentators read that word as a name instead of an exclamation: “Tob, let him do it.” Clearly, however, that is not his actual name. Kiersten Nielson argues that “the author’s anonymization of the man must…be an expression of indirect condemnation of him as a man who refuses to safeguard the good name of the family for posterity. He deserves to remain nameless.”[1]

Boaz summoned this nameless redeemer and he did so eagerly!

And he did so publically, not secretly. Boaz went to the city gate through which the workers would pass as they returned in the morning from their labors. He had no intention of working a sly deal. On the contrary, this would be handled in the full light of day and in the sight of all.

2 And he took ten men of the elders of the city and said, “Sit down here.” So they sat down. 3 Then he said to the redeemer, “Naomi, who has come back from the country of Moab, is selling the parcel of land that belonged to our relative Elimelech. 4 So I thought I would tell you of it and say, ‘Buy it in the presence of those sitting here and in the presence of the elders of my people.’ If you will redeem it, redeem it. But if you will not, tell me, that I may know, for there is no one besides you to redeem it, and I come after you.” And he said, “I will redeem it.” 5 Then Boaz said, “The day you buy the field from the hand of Naomi, you also acquire Ruth the Moabite, the widow of the dead, in order to perpetuate the name of the dead in his inheritance.” 6 Then the redeemer said, “I cannot redeem it for myself, lest I impair my own inheritance. Take my right of redemption yourself, for I cannot redeem it.”

Boaz summoned ten men to serve as witnesses of what was about to happen. It is not terribly clear whether this number was particularly significant. Concerning the ten witnesses, Leon Morris writes

Obviously this could give a solid body of witness, but whether there was any legal requirement met by this number or not our information from antiquity does not reveal. In more recent times, ten, of course, is a significant number. Thus ten men are required for a synagogue service. Slotki sees in the number “The quorum required for the recital of the marriage benedictions. Boaz held them in readiness for the pending ceremony.” However, he cites no evidence that the custom is so old. The Midrash Rabbah regards this passage as giving justification for ten at ‘the blessing of the bridegroom’ (vii. 8).[2]

Perhaps, then, there is custom behind ten witnesses. Perhaps customs grew out of Boaz’s summoning of these ten. Regardless, notice that Boaz sought a public redemption of Ruth, one that could not be questioned, one that had witnesses.

The transaction went as follows: Boaz informed the unnamed redeemer that he, the redeemer, had first rights to redeem the late Elimelech’s land from Ruth. There is considerable discussion about what this means since land did not pass from husband to wife at that time. Regardless, the redeemer had first rights if he so desired. And he did so desire. He said in the presence of all that he wanted the land. Then Boaz added a caveat that changed everything. If he bought the land, he informed him, he also redeemed Elimelech’s Moabite daughter-in-law, Ruth. “I cannot redeem it for myself,” the man said in recanting his claim, “lest I impair my own inheritance. Take my right of redemption yourself, for I cannot redeem it.”

This is a very interesting thing for him to say: “lest I impair my own inheritance.” Daniel Block gives a helpful explanation of what the redeemer likely meant.

Given his own age and the age of Ruth, he might have thought she might bear him no more than one child. Since this child would be legally considered the heir and descendant of Elimelech, upon the death of the go’el he would inherit the property that had come into his hands through this present transaction as well as the go’el’s inherited holdings. Furthermore, since the name of Elimelech had been established/raised up through the child, the go’el’s entire estate would fall into the line of Elimelech, and his own name would disappear. Third, in view of Boaz’s introduction of Ruth as “the Moabitess,” he might have pondered the ethnic implication of the transaction, concluding that his patrimonial estate would not be jeopardized by falling in to the hands of one with Moabite blood in his veins.[3]

The obstacle to Boaz’s redemption of Ruth had been removed! He could now secure her and bring her into his home. And he had achieved this in the sight of all.

Jesus, too, achieved the redemption of His people in the sight of all and not on the sly. “Nevertheless,” Jesus said in Luke 13:33, “I must go on my way today and tomorrow and the day following, for it cannot be that a prophet should perish away from Jerusalem.” So Jesus went through the city gates of Jerusalem only to come out of them again carrying a cross. In the sight of God and man, Jesus redeemed His bride. He was suspended between heaven and earth on the cross, bidding all to bear witness that He was laying indisputable claim to His bride by paying the price for her.

Christ redeemed fallen man in the presence of all, and this act of redemption was legally binding. So too was Boaz’s redemption of Ruth.

7 Now this was the custom in former times in Israel concerning redeeming and exchanging: to confirm a transaction, the one drew off his sandal and gave it to the other, and this was the manner of attesting in Israel. 8 So when the redeemer said to Boaz, “Buy it for yourself,” he drew off his sandal. 9 Then Boaz said to the elders and all the people, “You are witnesses this day that I have bought from the hand of Naomi all that belonged to Elimelech and all that belonged to Chilion and to Mahlon. 10 Also Ruth the Moabite, the widow of Mahlon, I have bought to be my wife, to perpetuate the name of the dead in his inheritance, that the name of the dead may not be cut off from among his brothers and from the gate of his native place. You are witnesses this day.” 11 Then all the people who were at the gate and the elders said, “We are witnesses. May the Lord make the woman, who is coming into your house, like Rachel and Leah, who together built up the house of Israel. May you act worthily in Ephrathah and be renowned in Bethlehem, 12 and may your house be like the house of Perez, whom Tamar bore to Judah, because of the offspring that the Lord will give you by this young woman.”

It was an odd way to signify that the transaction was complete, official, binding. The redeemer took off his shoe and handed it to Boaz, signifying thereby that he was letting the right of redemption pass him by so that it could rest on eager Boaz. Thus, Boaz redeemed Naomi’s land and Naomi and Ruth.

But here there is something interesting in our text, something unexpected, something frankly unusual. There are two words that are used in this conversation between Boaz and the redeemer. The word for “redeem” is the Hebrew word ga’al and the word for “buy” or “acquire” is the Hebrew word qanah. You can see both at play in the heart of the conversation from verses 4-6.

4 So I thought I would tell you of it and say, ‘Buy it in the presence of those sitting here and in the presence of the elders of my people.’ If you will redeem it, redeem it. But if you will not, tell me, that I may know, for there is no one besides you to redeem it, and I come after you.” And he said, “I will redeem it.” 5 Then Boaz said, “The day you buy the field from the hand of Naomi, you also acquire Ruth the Moabite, the widow of the dead, in order to perpetuate the name of the dead in his inheritance.” 6 Then the redeemer said, “I cannot redeem it for myself, lest I impair my own inheritance. Take my right of redemption yourself, for I cannot redeem it.”

What is unusual about this is the word “buy.” In the legal requirements of the redeemer, the language was not of buying but of redeeming. And a redeemer certainly would not speak of buying or acquiring a person. It is very unusual that Boaz speaks of buying Ruth. Furthermore, it is very unusual to see these two words, redeem and acquire, used together to describe a human transaction.

In a fascinating article entitled “‘Redemption-Acquisition’: The Marriage of Ruth as a Theological Commentary on Yahweh and Yaweh’s People,” Brad Embry points out the heart of the issue.

While the two terms redeem and acquire are fairly common, their use together is not, only appearing explicitly in two other places apart from Ruth: Exod 15:13-15 and Ps 74:2…[T]he concept of “redeem-acquire” is implicit in two more selections: Deut 32:6 and Isa 11:11. In the case of each of the other intertextual references (Exod 15:13-19; Ps 74:2; Deut 32:6; Isa 11:11), the complex “redeem-acquire” is employed exclusively to express an action undertaken by Yahweh on behalf of Israel and likely draws on the exodus tradition. In the story of Ruth, two things seem to fall under qualification for redemption-acquisition. The first is the land for sale by Naomi. The second is Ruth. As such, only in the book of Ruth is the complex “redeem-acquire” used to articulate the relationship between two human characters. In this way, the author of Ruth has constructed a story in which two of the primary characters, while functioning within an unfolding story of loss and restoration for a particular household, can also be emblematic of Yahweh’s actions on behalf of Israel.[4]

This is profoundly important. This is why I say that here the lower and upper levels of our story converge, for it is only in Yahweh’s redemption of His people that the “redeem-acquire” formula is used. For instance, in Exodus 15:13-16.

13 “You have led in your steadfast love the people whom you have redeemed; you have guided them by your strength to your holy abode. 14 The peoples have heard; they tremble; pangs have seized the inhabitants of Philistia. 15 Now are the chiefs of Edom dismayed; trembling seizes the leaders of Moab; all the inhabitants of Canaan have melted away. 16 Terror and dread fall upon them; because of the greatness of your arm, they are still as a stone, till your people, O Lord, pass by, till the people pass by whom you have purchased.

Furthermore, in Psalm 74 we find the same formula.

2 Remember your congregation, which you have purchased of old, which you have redeemed to be the tribe of your heritage! Remember Mount Zion, where you have dwelt.

Do you see why this matters? When Boaz used the formula “redeem-acquire” in talking to the redeemer about Ruth, he was using a formula that is only used to refer to God’s redemption of His people. Thus, when Boaz spoke of redeeming and buying Ruth, he was painting a picture that theretofore had only been painted to describe Yahweh God’s love for us. In this way, the lower level and the upper level converge: Boaz’s redemption and purchase of Ruth is a picture of God’s redemption and purchase of His people, then, now, and forever. It is how God loves us.

Does this language of purchase carry over into the New Testament? Indeed it does. In 1 Corinthians 6, Paul writes:

19 Or do you not know that your body is a temple of the Holy Spirit within you, whom you have from God? You are not your own, 20 for you were bought with a price. So glorify God in your body.

In Revelation 5, we read:

8 And when he had taken the scroll, the four living creatures and the twenty-four elders fell down before the Lamb, each holding a harp, and golden bowls full of incense, which are the prayers of the saints. 9 And they sang a new song, saying, “Worthy are you to take the scroll and to open its seals, for you were slain, and by your blood you ransomed people for God from every tribe and language and people and nation, 10 and you have made them a kingdom and priests to our God, and they shall reign on the earth.”

The word for “ransom” in verse 9 is the same word Paul uses in 1 Corinthians 6 for “bought.”

What a glorious, beautiful truth! The God who purchased His people out of slavery in Egypt is the same God who purchases His people through the blood of Christ our Redeemer. Jesus our Redeemer buys us on the cross. He lays down His life to purchase us by paying the debt we cannot pay, and the elements on this very table speak of that amazing purchase. The juice and the bread are symbols of the blood and body of Christ. They are the means by which He purchases all who will come to Him in faith and repentance, all who will lay themselves at His feet.

Behold the Lamb who was slain! Behold the God who purchases His bride! Behold the Redeemer who is eager to save!

[1] Kirsten Nielson, Ruth. The Old Testament Library. (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1997), p.83,n.124.

[2] Arthur E. Cundall and Leon Morris (2008-09-19). TOTC Judges & Ruth (Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries) (Kindle Locations 4442-4447). Inter-Varsity Press. Kindle Edition.

[3] Daniel I. Block, Judges, Ruth. The New American Commentary. Vol. 6. Gen. Ed., E. Ray Clendenen. (Nashville, TN: B&H Publishing Group, 1999), p.660.

[4] Brad Embry. “‘Redemption-Acquisition’: The Marriage of Ruth as a Theological Commentary on Yahweh and Yaweh’s People.” Journal of Theological Interpretation. 7.2 (2013), p.258-259. This is a very insightful article that I find quite persuasive. Embry’s argument has strongly influenced my argument in this portion of the sermon.

Exodus 15:22-27

22 Then Moses made Israel set out from the Red Sea, and they went into the wilderness of Shur. They went three days in the wilderness and found no water. 23 When they came to Marah, they could not drink the water of Marah because it was bitter; therefore it was named Marah. 24 And the people grumbled against Moses, saying, “What shall we drink?” 25 And he cried to the Lord, and the Lord showed him a log, and he threw it into the water, and the water became sweet. There the Lord made for them a statute and a rule, and there he tested them, 26 saying, “If you will diligently listen to the voice of the Lord your God, and do that which is right in his eyes, and give ear to his commandments and keep all his statutes, I will put none of the diseases on you that I put on the Egyptians, for I am the Lord, your healer.” 27 Then they came to Elim, where there were twelve springs of water and seventy palm trees, and they encamped there by the water.

Have you ever noticed that valleys tend to come fast on the heels of mountaintops? Why is it that the greatest moments tend to give rise to the most anticlimactic moments? There are times when we are tempted to agree with T.S. Eliot’s famous conclusion to his poem “The Hollow Men.”

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.

There is almost a cruel irony to life.

I once spoke with a man who told me that his great-grandfather survived the brutal and bloody 1862 Battle of Antietam in which the combined number of dead, wounded, and missing was over 22,000. Shortly after the end of the war, however, a hoisted cotton bail fell on his grandfather and killed him.

In the oft-repeated words of Kurt Vonnegut from Slaughterhouse Five, “So it goes.”

Perhaps that is how the Israelites felt when they came to the bitter waters of Marah after having just survived the Red Sea. Which is to say that it would indeed be ironic to survive the Red Sea only to die beside an oasis. But for a moment this looked like exactly what was about to happen.

For a moment.

God delivers the grumbling children of Israel through a contrasting water miracle.

The Israelites have just been delivered from Pharaoh’s army in the startling passage through the Red Sea. God is on their side. Then, in the first part of Exodus 15, they rejoice with singing and dancing! These are thrilling times indeed. Now they set out toward home. But there is a problem.

22 Then Moses made Israel set out from the Red Sea, and they went into the wilderness of Shur. They went three days in the wilderness and found no water. 23 When they came to Marah, they could not drink the water of Marah because it was bitter; therefore it was named Marah. 24 And the people grumbled against Moses, saying, “What shall we drink?”

Three days in and the people, understandably, were parched. Surely God did not bring them through the Red Sea simply to have them die in the wilderness, did He? The “water of Marah” may refer either to “the Bitter Lakes” or an oasis called Bir Marah “where the water is saline with heavy mineral content.”[1]

Clearly this was an untenable situation. Hundreds of thousands of thirsty Israelites hear that water is near. Their hearts soar with expectation! They rejoice at the faithful provision of God. They begin to press forward. Then those at the back hear an approaching murmur. It grows louder as it spreads. What is that they are saying? “It is undrinkable! It is marah! It is bitter!”

You will perhaps recognize this word marah. It is what Naomi renames herself in the end of Ruth 1 as she launches her complaint against God to the Bethlehemite women. Bitter! The water is bitter!

Nobody likes undrinkable water, not even the Lord! As He says to the church of Laodicea in Revelation 3:15-16 concerning their bland non-commitment, “I know your works: you are neither cold nor hot. Would that you were either cold or hot! So, because you are lukewarm, and neither hot nor cold, I will spit you out of my mouth.” Furthermore, in Jude 12, Jude writes of the taunting disappointment of expecting water and finding none when he metaphorically describes the false teachers as “waterless clouds.”

Whether it be grossly lukewarm or bitter or merely a mirage that does not deliver what it promises, undrinkable water is a plague. Thus, they “grumbled” against Moses. Moses, in turn, “cried to the Lord.”

But before we see how this episode concludes, let us ponder a moment on the nature of human fickleness. To respond with unraveling fear before a bitter oasis when the Lord God miraculous delivered you through the waters of the Red Sea just three days earlier is as glorious an example of human fickleness as one could ever want. “What is remarkable,” Philip Ryken writes, “is not that God was able to perform the miracle at Marah, but that he was willing to do it for such a bunch of malcontents…God’s grace is so amazing that he even provides for whiners, provided that we really are his children.”[2]

This is very well said. How very, very quickly we forget. And this is why it is difficult to judge the children of Israel too harshly. Do we not do the exact same thing? Do we not fret about oases after being delivered through seas? Certainly we do. No sooner has the Lord delivered us from life-threatening challenges than we start complaining about challenges that are trifles in comparison.

To be sure, the prospect of slowly dying from lack of water in the wilderness is no mere trifle, but, again, this episode happened after the most staggering act of miraculous deliverance in human history to date. The Lord, however, is indeed merciful to His grumbling children.

25a And he cried to the Lord, and the Lord showed him a log, and he threw it into the water, and the water became sweet.

Once again, God saved His people in a watery miracle, this time by having them throw “a log” into the water that rendered it drinkable. Victor Hamilton explains that, “ʿĒṣ normally means “tree,” but “stick, twig” is the meaning in some passages (Ezek. 37: 16, 19).”[3] Regardless, it had the desired effect.

Was the tree just a tree that God miraculous enabled to change the nature of the water, or did the tree have inherent neutralizing properties unknown to the Israelites and God simply pointed them to the natural solution to their predicament? Both cases have been argued. Roy Honeycutt, for instance, suggests that “the tree possessed purifying qualities, and the Lord utilized the created order for the fulfillment of his own purposes. The latent energies of the world came to life under the responsible direction of a man committed to the will of God, and Israel was delivered.”[4]

I personally see this as a miraculous transformation of otherwise normal wood into an agent of change for the water. Regardless, God showed up once again and saved His people. I say this is a “contrasting water miracle” because it does indeed offer ironic contrasts to the miracle of the Red Sea. Consider:

- At the Red Sea Israel did not want to go into the water but they had to. At Marah Israel wanted to get into the water but could not at first.

- At the Red Sea Israel thought they would die beside a large body of water. At Marah Israel thought they would die before a small body of water.

- At the Red Sea God saved Israel by keeping them from contact with the water. At Marah God saved Israel by enabling them to have contact with the water.

- At the Red Sea Israel moved from fear to joy. At Marah Israel moved from joy to fear to joy again.

It is indeed intriguing to consider the nature of these watery miracles. The constant, however, was the love and grace and provision of Almighty God, Who delivered His people.

God delivers His children through an early giving of Law.

There is another miracle here, and it does not involve water. In fact, we may be tempted not to consider it a miracle at all, but truly it is. I speak here of God’s giving of an initial law to Israel as well as His charging them to obey and live.

25b There the Lord made for them a statute and a rule, and there he tested them, 26 saying, “If you will diligently listen to the voice of the Lord your God, and do that which is right in his eyes, and give ear to his commandments and keep all his statutes, I will put none of the diseases on you that I put on the Egyptians, for I am the Lord, your healer.” 27 Then they came to Elim, where there were twelve springs of water and seventy palm trees, and they encamped there by the water.

I say that this giving of “a statute and a rule” is a miracle because revelation always is. Out of the abundance of His own mercies, God established His law with His people. We are not at Sinai yet and the great giving of the Law, but here we find a kind of proto-law. Furthermore, he reinforced in their minds that obedience will lead to life. Specifically, the Lord told Israel that if they were obedient and kept His commandments, “I will put none of the diseases on you that I put on the Egyptians”

That was an interesting way to put it: “I will put none of these diseases on you.” Victor Hamilton has offered some fascinating insights into how we likely should understand this saying

To what might “the sicknesses that I set upon Egypt” refer? Possibly characteristic Egyptian sicknesses like dysentery or elephantiasis. More likely the reference is to the plagues of chaps. 7– 12, although the word “sickness” is never used to describe any of them. If this is correct, the plagues in Egypt begin with nobody being “able to drink the water” (Exod. 7: 18, 21, 24). Similarly, Israel’s journey Canaan-ward begins with nobody “able to drink the water.” Egypt’s water got a staff (Exod. 7: 17). Israel’s water got a stick.[5]

Hamilton is right. This is likely a reference to the plagues put on Egypt. God is telling His people that He will not do to them what He did to Egypt, but they need to trust in Him and walk with Him and obey Him.

Hamilton’s point about the first plague of Egypt rendering the water undrinkable (by turning the water of the Nile into blood) is important. Perhaps God’s assurance that He would not do to Israel what He did to Egypt is evidence that the Israelites were grumbling precisely this accusation beside the bitter waters of Marah. Perhaps some of them were thinking, “He rendered their water undrinkable. Now He has done it to us. He has brought us out here to strike us with the same plagues with which He struck Egypt.”

To which God says, “No! I will not treat my own people as I treated wicked, murderous Egypt. But you must walk with Me and obey Me.”

This principle still applies. God is immutable, unchanging, and does not vary how He deals with His people. To obey God’s commandments is to walk the path of life. To disobey is to walk the path of death.

Of course, this presents us with a dilemma, as none of us are able to walk the path of obedience with perfection or complete purity. This is where the gospel shines the most splendidly, for this gospel tells us that there was One who walked the path of perfect obedience for us: Jesus. When we come to Him, we are covered by His righteousness, His obedience, and His perfection. This, of course, must not give rise to thoughts of lawlessness on our parts, as if the righteousness of Christ could be stolen and manipulated by wicked hands. In truth, the man who comes to Christ will never dare consider that the righteousness of God is in any way a license for sin. Paul deals a definitive deathblow to such an absurd idea in Romans 6.

1 What shall we say then? Are we to continue in sin that grace may abound? 2 By no means! How can we who died to sin still live in it? 3 Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? 4 We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life. 5 For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we shall certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his. 6 We know that our old self was crucified with him in order that the body of sin might be brought to nothing, so that we would no longer be enslaved to sin. 7 For one who has died has been set free from sin. 8 Now if we have died with Christ, we believe that we will also live with him. 9 We know that Christ, being raised from the dead, will never die again; death no longer has dominion over him. 10 For the death he died he died to sin, once for all, but the life he lives he lives to God. 11 So you also must consider yourselves dead to sin and alive to God in Christ Jesus. 12 Let not sin therefore reign in your mortal body, to make you obey its passions. 13 Do not present your members to sin as instruments for unrighteousness, but present yourselves to God as those who have been brought from death to life, and your members to God as instruments for righteousness. 14 For sin will have no dominion over you, since you are not under law but under grace.

Here we begin to understand that what God did for Israel at the waters of Marah God does for the hearts of all who will come to Christ: He changes the bitter into sweet, the unpalatable into the delightful, death into life. God is still in the business of delivering His grumbling children. He does so through and in Jesus, the King who makes all things new.

Are you stuck in the bitter waters of Marah? Come to the everlasting waters of Christ! Take His hand and take His way and He will lead you home.

[1] John H. Walton, Victor H. Matthews and Mark W. Chavalas, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000), p.91.

[2] Philip Graham Ryken, p.422.

[3] Hamilton, Victor P. (2011-11-01). Exodus: An Exegetical Commentary (Kindle Locations 8013-8014). Baker Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

[4] Roy L. Honeycutt, Jr. “Exodus.” The Broadman Bible Commentary. Vol.1, Revised (Nashville, TN: Broadman Press, 1969), p.379.

[5] Hamilton, Victor P., Kindle Locations 8129-8133.

A Quick Note on an Interesting Squabble

My friend Eugene Curry sent me Edward Feser’s latest salvo in the fracas between him and David Bentley Hart. I will not summarize the squabble here because Feser lays out a bit of a timeline in his post. It is an interesting discussion, and a rather heady one. I daresay that ego certainly appears to be playing its role on both sides of what is otherwise an insightful exchange.

My friend Eugene Curry sent me Edward Feser’s latest salvo in the fracas between him and David Bentley Hart. I will not summarize the squabble here because Feser lays out a bit of a timeline in his post. It is an interesting discussion, and a rather heady one. I daresay that ego certainly appears to be playing its role on both sides of what is otherwise an insightful exchange.

I am intrigued, however, by Feser’s reference to the “terrorism of obscurantism” and think that is probably a reasonable charge to lay at Hart’s feet. I am, again, much more familiar with Hart, and have read with great profit his Atheist Delusions and The Doors of the Sea. That being said, I have been disappointed with Hart on two fronts: (a) his overly-simplistic skewering of conservative hermeneutics and (b) his (in my opinion) caricaturing of William Lane Craig. Even so, I appreciate Hart’s work on atheism and theodicy, though he likely does at times traffic in excessive obscurantism. Here’s the Feser post.

Barry Hankins’ Enthralling 2007 Fides et Historia Piece on Francis Schaeffer’s Conflict With Christian Historians

I have only recently read Barry Hankins’ article, “‘I’m Just Making a Point’: Francis Schaeffer and the Irony of Faithful Christian Scholarship.” If you are familiar with the late Francis Schaeffer or, if like me and countless others, you were influenced at some point in your life by his writings, you will likely find this article troubling and enthralling.

I have only recently read Barry Hankins’ article, “‘I’m Just Making a Point’: Francis Schaeffer and the Irony of Faithful Christian Scholarship.” If you are familiar with the late Francis Schaeffer or, if like me and countless others, you were influenced at some point in your life by his writings, you will likely find this article troubling and enthralling.

As I say, like many others, I was deeply influenced by Francis Schaeffer, particularly as a teenager and a college student. Those who were impacted by Schaeffer oftentimes have a similar story: he awakened within us the possibility of being intellectually satisfied Christians who could emerge from the fundamentalist ghetto and engage the culture without hating or hiding from it. Especially those coming out of fundamentalism found reading Schaeffer to be a heady, exhilarating, and even dangerous experience. Could one really actually like and appreciate Bob Dylan, Led Zeppelin, Albert Camus, etc? For those raised in certain branches of conservative Southern Protestantism in particular, this was gloriously liberating.

But, like many others, Schaeffer managed to sow the seeds that would oftentimes grow to cause his fans to question him. For me, this happened when, under Schaeffer’s influence, I actually read Soren Kierkegaard. In short, the experience caused me to question Schaeffer’s method and the very broad brush with which he painted (in the case of Kierkegaard, this was a very negative brush). Furthermore, some of Schaeffer’s conclusion are too neat, too tidy, and lacking in the nuance that real life usually presents the observer.

At the end of the day, I retain a fondness for Schaeffer, a fondness that is somewhat buttressed by nostalgia, but now it is measured with a strong degree of hesitation and a recognition of his limitations and, at points, outright mistakes. Schaeffer opened a door for me. Having walked through it, I realize with a degree of sadness that I have, in part, parted company with him.

In part.

Hankins’ article is a fascinating look at Schaeffer’s falling out with Christian historians Mark Noll, George Marsden, and Ronald Wells over some of the issues I have referenced above. I offer a pdf of the article here as a fascinating case study in competing approaches to Christianity and culture and the Christian understanding of history and philosophy.

“‘I’m Just Making a Point’: Francis Schaeffer and the Irony of Faithful Christian Scholarship”

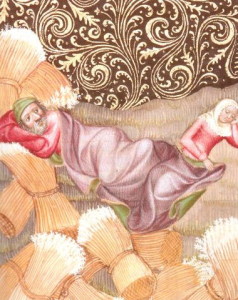

Ruth 3

1 Then Naomi her mother-in-law said to her, “My daughter, should I not seek rest for you, that it may be well with you? 2 Is not Boaz our relative, with whose young women you were? See, he is winnowing barley tonight at the threshing floor. 3 Wash therefore and anoint yourself, and put on your cloak and go down to the threshing floor, but do not make yourself known to the man until he has finished eating and drinking. 4 But when he lies down, observe the place where he lies. Then go and uncover his feet and lie down, and he will tell you what to do.” 5 And she replied, “All that you say I will do.” 6 So she went down to the threshing floor and did just as her mother-in-law had commanded her. 7 And when Boaz had eaten and drunk, and his heart was merry, he went to lie down at the end of the heap of grain. Then she came softly and uncovered his feet and lay down. 8 At midnight the man was startled and turned over, and behold, a woman lay at his feet! 9 He said, “Who are you?” And she answered, “I am Ruth, your servant. Spread your wings over your servant, for you are a redeemer.” 10 And he said, “May you be blessed by the Lord, my daughter. You have made this last kindness greater than the first in that you have not gone after young men, whether poor or rich. 11 And now, my daughter, do not fear. I will do for you all that you ask, for all my fellow townsmen know that you are a worthy woman. 12 And now it is true that I am a redeemer. Yet there is a redeemer nearer than I. 13 Remain tonight, and in the morning, if he will redeem you, good; let him do it. But if he is not willing to redeem you, then, as the Lord lives, I will redeem you. Lie down until the morning.” 14 So she lay at his feet until the morning, but arose before one could recognize another. And he said, “Let it not be known that the woman came to the threshing floor.” 15 And he said, “Bring the garment you are wearing and hold it out.” So she held it, and he measured out six measures of barley and put it on her. Then she went into the city. 16 And when she came to her mother-in-law, she said, “How did you fare, my daughter?” Then she told her all that the man had done for her, 17 saying, “These six measures of barley he gave to me, for he said to me, ‘You must not go back empty-handed to your mother-in-law.’” 18 She replied, “Wait, my daughter, until you learn how the matter turns out, for the man will not rest but will settle the matter today.”

Oddly enough, our chapter made the news recently. On May 12, 2015, a BBC article entitled “Rare 1611 ‘Great She Bible’ found in Lancashire church” tells of a British church’s discovery of a most interesting Bible in their church.

A rare 400-year-old Bible worth about £50,000 has been discovered in a Lancashire village church.

Printed in 1611 and known as the “Great She Bible”, it is one of the earliest known copies of the King James Version (KJV) of the Christian holy book.

It will be displayed at St Mary’s Parish Church in Gisburn on Saturday.

The Reverend Anderson Jeremiah and the Reverend Alexander Baker found the old book following their appointment at the church last August.

It is called a “She Bible” because Chapter 3, Verse 15 of the Book of Ruth mistakenly reads: “She went into the city”.

Thought to be typographical mistake, this verse was changed from another KJV edition which said “He”.

The Bible has been assessed and authenticated by the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association.

Only a handful of the “She Bibles” still exist. Oxford and Cambridge Universities have one, as do Salisbury, Exeter and Durham cathedrals.[1]

Strange, no? The Hebrew text says that “he” went into the city in Ruth 3:15, whereas the context clearly demands that is was “she” who went into the city. So this Great She Bible is so named because of a translation issue surrounding a particular part of a particular verse in Ruth 3. It is humorous, really, because the great scandal of the chapter is not that she left the threshing floor and went into the city but rather that she, Ruth, left the city and came to the threshing floor!

This is a rather eyebrow-raising chapter, and a profoundly important one, for in Ruth 3 Ruth does something that, if taken the wrong way, could have seriously backfired and put her in a very dangerous situation. If received, it could open the door for her and Boaz’s relationship to move to new heights. I am talking about Ruth coming to Boaz in the night and making a surprising statement of love and devotion to him in a rather surprising way.

The chapter has been subject to various interpretations over the years. Katharine Sakenfeld writes that she has talked with people who see what happens in Ruth 3 as “a steamy tryst between mutually desiring persons (in the genre of the North American soap opera or formulaic romance novel),” whereas others she has spoken with see it as “a beautiful but needy young Ruth forcing herself to relate to a rough, pot-bellied, snaggle-toothed (but rich) old man for the sake of her mother-in-law,” and still others who see it as “a wily, scheming Ruth cooperating with Naomi to compromise and thus force the hand of the most handsome and wealthy bachelor of the community.”[2]

In truth, the context and tone and details of the story would suggest that what we have here is, again, a shocking declaration of love. Ruth, to use our terminology, really puts herself out there! There is nothing sinful in what she does, though there is something very unorthodox about it. On the upper level of the story, what we have here is a plea for salvation that is met by the offered redemption of a loving God.

We will be approaching Ruth 3 with the following thesis in mind: redemption happens when desperate need leads to a radical plea for salvation and is met with saving grace. We will deal first with the nature of the radical plea.

Redemption happens when desperate need leads to a radical plea for salvation and is met with saving grace.

As chapter two ends, Ruth has recounted to her mother-in-law that is was one of their kinsman-redeemers, Boaz, who had so richly and generously blessed the women through the kindness and provision and offered her. Naomi apparently realized that this relationship could become even more.

1 Then Naomi her mother-in-law said to her, “My daughter, should I not seek rest for you, that it may be well with you? 2 Is not Boaz our relative, with whose young women you were? See, he is winnowing barley tonight at the threshing floor. 3 Wash therefore and anoint yourself, and put on your cloak and go down to the threshing floor, but do not make yourself known to the man until he has finished eating and drinking. 4 But when he lies down, observe the place where he lies. Then go and uncover his feet and lie down, and he will tell you what to do.” 5 And she replied, “All that you say I will do.” 6 So she went down to the threshing floor and did just as her mother-in-law had commanded her. 7 And when Boaz had eaten and drunk, and his heart was merry, he went to lie down at the end of the heap of grain. Then she came softly and uncovered his feet and lay down. 8 At midnight the man was startled and turned over, and behold, a woman lay at his feet! 9 He said, “Who are you?” And she answered, “I am Ruth, your servant. Spread your wings over your servant, for you are a redeemer.”

Let us first understand the historical setting for what happens here. The harvest has come to a conclusion and now Boaz has come to winnow the harvest on the threshing floor. J. Hardee Kennedy explains:

The threshing floor probably was privately owned by Boaz and located on his property. In accord with general practice, however, it may have been common to the whole village (cf. 2 Sam. 24:15-25). There the ripe sheaves were brought and loosed in a circle on the smooth hard surface, possibly a flat rock floor. The grain was separated from the straw by the trampling of the oxen and the cutting of the sled or roller studded with sharp pieces of stone and metal (cr. Jer. 51:33; Mic. 4:12-13). In the winnowing process the threshed grain was tossed high in the air with shovels or forks and the chaff blown aside by the wind. Afterward the grain was gathered in a heap on the firm ground or smooth rock floor.

Winnowing took place in the evening, usually from four or five o’clock until shortly after sunset, when a cool breeze blew in from the Mediterranean Sea. Apparently the workmen often closed their day’s labor by celebrating the harvest with considerable license, eating and drinking (v.3). Afterward they slept on the threshing floor to protect the grain.[3]

This is the situation into which Naomi sent her daughter-in-law. She first told Ruth to wash and perfume herself. Kennedy rather humorously writes that Naomi “advised Ruth to prepare for maximum impression.”[4] Indeed she did!

Naomi tells Ruth that she is looking out for Ruth’s well being. Undoubtedly that is true, but it is not the whole truth. In point of fact, the security that Boaz would offer Ruth would naturally extend to Naomi as well. This is not to say that Naomi was being manipulative per se, but one cannot help but chuckle a bit at the obvious dynamics at play in this older woman’s fairly aggressive maneuvering of her daughter-in-law toward a desired end.

It should be pointed out that many people have read into Ruth 3 an outright seduction. In point of fact, if one were to read Ruth 3 in this way it would make Boaz’s invocation of the Lord’s name once he discovered Ruth essentially nonsensical. Boaz saw Ruth’s behavior here as a chaste act of love and not as something tawdry. The 5th century church father, Theodoret of Cyr, wrote that, “[Naomi] suggests to her that she sleep at Boaz’s feet, not that she might sell her body (for the words of the narrative signify the opposite); rather, she trusts the man’s temperance and judgment.” Furthermore, Theodoret argued that Boaz “praised Ruth’s deed and, moreover, he did not betray temperance, but he kept to the law of nuptial congress.”[5]

This is not merely a church father trying to protect Ruth’s dignity. This is the most natural reading of the text.

Ruth, we are told, slipped onto the threshing floor, approached sleeping Boaz in the night, uncovered his feet, and lay down there. When he awoke, he was understandably startled. When verse 8 tells us that Boaz was “startled” it uses a Hebrew word that carries the meaning of “seized with fear and shivering.” Some have suggested that it might be a reflection of the fear that many ancient men had of the demon, Lilith, who would allegedly seduce men during the night and steal their power.[6] Perhaps. Or perhaps it is simply the natural shock any person would feel when awakening and realizing that another human being is essentially in bed with them when there should be no other human being in bed with them!

Boaz awoke and asked Ruth who she was. “I am Ruth, your servant. Spread your wings over your servant, for you are a redeemer.” “Spread your wings over your servant” was an idiomatic expression that meant, “Marry me.” It “reflected the custom, still practiced by some Arabs, of a man’s throwing a garment over the woman he has decided to take as his wife.”[7]

In short, Ruth proposed to Boaz.

One cannot overstate just how risky, how dangerous, how unorthodox, and how shocking an act this was for a foreign woman or any woman at this time to do. In doing so, Ruth put herself completely at Boaz’s mercy. By lying at his feet, she was making a symbolic statement of devotion and submission to Boaz. It was a touching act, but, by any reasonable human standard, it was amazingly inappropriate.

Yet, she did it. Why? One does not feel that she was begrudgingly obeying her mother-in-law’s command in so doing. Rather, while Naomi suggested the idea, Ruth seems to have been in complete agreement, to the extent that it must be said that the act really and truly was Ruth’s.

By why? Undoubtedly she saw in Boaz the qualities of the kind of man to whom she wanted to attach herself. Futhermore, Ruth said, “I am Ruth, your servant. Spread your wings over your servant, for you are a redeemer.” This should not be seen as coldly pragmatic or as calculatingly self-serving. We have every reason to think to Ruth felt drawn to Boaz and highly esteemed him. Yet she also realized that this man is in a position to take her into his family, to marry her, and to save her.

At this point, the lower level love story and the upper level story of salvation come very close to each other. Just as Ruth asks Boaz for loving salvation, so we too cry out to God to save us. And the scandalous audacity of Ruth’s asking must not be forgotten. Redemption happens when desperate need leads to a radical plea for salvation and is met with saving grace.

Ruth had a growing love for Boaz and she had desperate need. Thus, she offered a radical plea for salvation.

It is interesting how, when people grow truly desperate for Jesus, they forget about the maintaining their dignity and they radically reach for Christ simply because they must have Him. Mark 2 offers one of the truly beautiful examples of this kind of radical plea for salvation.

1 And when he returned to Capernaum after some days, it was reported that he was at home. 2 And many were gathered together, so that there was no more room, not even at the door. And he was preaching the word to them. 3 And they came, bringing to him a paralytic carried by four men. 4 And when they could not get near him because of the crowd, they removed the roof above him, and when they had made an opening, they let down the bed on which the paralytic lay. 5 And when Jesus saw their faith, he said to the paralytic, “Son, your sins are forgiven.”

So desperate were these men to see the Lord Jesus heal the paralytic that they ripped the roof off of a house to get him near. Behold the scandalous, risking, no-holding-back nature of the sinner’s plea for salvation! And behold the love of Christ, who looks upon such audacious efforts and says, “Son, your sins are forgiven.”

Perhaps less dramatically, Zacchaeus’ charming and moving efforts in Luke 19 provide another example.