The original article can be viewed here.

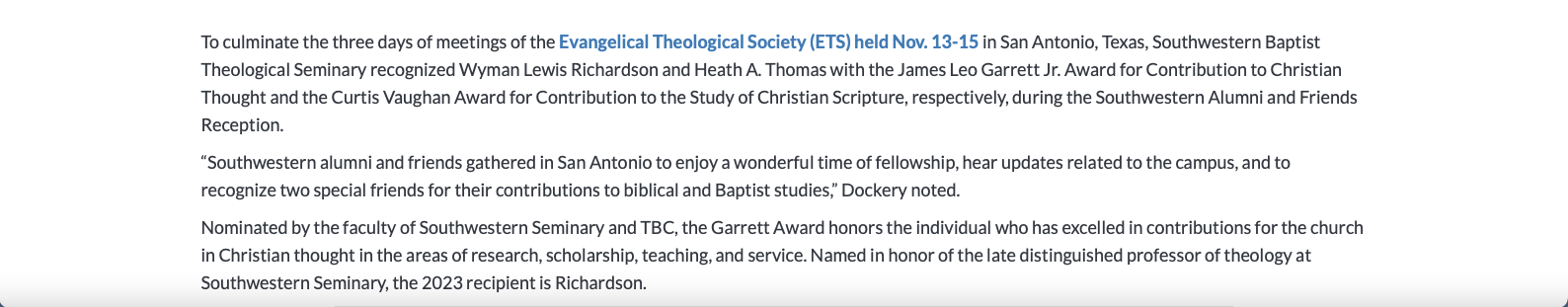

Amos 9

1 I saw the Lord standing beside the altar, and he said: “Strike the capitals until the thresholds shake, and shatter them on the heads of all the people; and those who are left of them I will kill with the sword; not one of them shall flee away; not one of them shall escape. 2 “If they dig into Sheol, from there shall my hand take them; if they climb up to heaven, from there I will bring them down. 3 If they hide themselves on the top of Carmel, from there I will search them out and take them; and if they hide from my sight at the bottom of the sea, there I will command the serpent, and it shall bite them. 4 And if they go into captivity before their enemies, there I will command the sword, and it shall kill them; and I will fix my eyes upon them for evil and not for good.” 5 The Lord God of hosts, he who touches the earth and it melts, and all who dwell in it mourn, and all of it rises like the Nile, and sinks again, like the Nile of Egypt; 6 who builds his upper chambers in the heavens and founds his vault upon the earth; who calls for the waters of the sea and pours them out upon the surface of the earth—the Lord is his name. 7 “Are you not like the Cushites to me, O people of Israel?” declares the Lord. “Did I not bring up Israel from the land of Egypt, and the Philistines from Caphtor and the Syrians from Kir? 8 Behold, the eyes of the Lord God are upon the sinful kingdom, and I will destroy it from the surface of the ground, except that I will not utterly destroy the house of Jacob,” declares the Lord. 9 “For behold, I will command, and shake the house of Israel among all the nations as one shakes with a sieve, but no pebble shall fall to the earth. 10 All the sinners of my people shall die by the sword, who say, ‘Disaster shall not overtake or meet us.’ 11 “In that day I will raise up the booth of David that is fallen and repair its breaches, and raise up its ruins and rebuild it as in the days of old, 12 that they may possess the remnant of Edom and all the nations who are called by my name,” declares the Lord who does this. 13 “Behold, the days are coming,” declares the Lord, “when the plowman shall overtake the reaper and the treader of grapes him who sows the seed; the mountains shall drip sweet wine, and all the hills shall flow with it. 14 I will restore the fortunes of my people Israel, and they shall rebuild the ruined cities and inhabit them; they shall plant vineyards and drink their wine, and they shall make gardens and eat their fruit. 15 I will plant them on their land, and they shall never again be uprooted out of the land that I have given them,” says the Lord your God.

Charles Spurgeon, that great preacher of yesteryear, once envisioned himself walking inside of a prison. Hear what he says:

I feel as if I were walking along a corridor, and I see a number of cells of the condemned. As I listen at the keyhole, I can hear those inside weeping in doleful, dolorous dirges. “There is no hope, no hope, no hope.” I can see the warden at the other end, smiling calmly to himself, as he knows that none of the prisoners can come out as long as they say there is no hope. It is a sign that their manacles are not broken and that the bolts of their cells are not removed.[1]

Imprisoned…by a lack of hope.

Amos is a book that is heavy on judgment. I do not say this as a criticism of the prophet. He was a faithful conveyor of God’s word and I certainly am not critical of God! If you think the Lord’s words have been too severe, go back to the beginning of the book and consider again the shocking severity of Israel’s sin! God was merciful to warn them at all. He did not have to. They were begging for judgment.

Yes, the book is a heavy book, a book of judgment, a book of woe. One is tempted to give up hope when one hears the searing, jarring, unrelenting words of judgment on its pages. After all, does our sin not deserve the same severity?

But as we conclude this book, I would like to address those of you here this morning who, like Spurgeon’s despondent prisoners, have no hope.

I would like to address the hopeless.

I would like to address the “I have done too much damage!”

I would like to address the “My family would be better off without me!”

I would like to address the “If they knew how I have messed up, they would never forgive me!”

I would like to address the “Hell awaits me, and I have no hope of heaven!”

I would like to address the “Maybe I will just end it all.”

I would like to address the fearful.

The condemned.

The “I have got it coming!”

The “God must hate me!”

The “I hate myself!”

And I would like to say this to you, on the basis of Amos 9 and on the basis of the whole of scripture and on the basis of the cross: In the darkest night of your own doom, there is yet hope! There is still hope! That tiny little flicker is there if you will look for it: that is hope! It is not over yet! Hell need not be your destination! God’s love is still offered to you! There is hope!

Three little words. Three little words in Amos 9 that dare to give us hope. In the midst of all these words of judgment, three words call to us to hope!

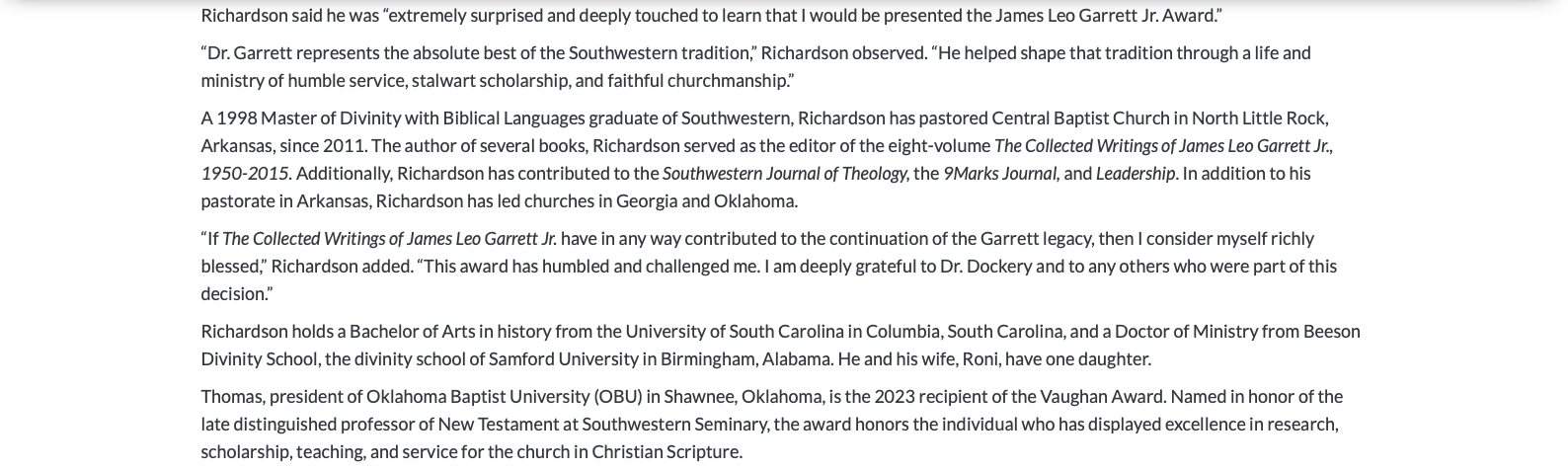

Amos 8

1 This is what the Lord God showed me: behold, a basket of summer fruit. 2 And he said, “Amos, what do you see?” And I said, “A basket of summer fruit.” Then the Lord said to me, “The end has come upon my people Israel; I will never again pass by them. 3 The songs of the temple shall become wailings in that day,” declares the Lord God. “So many dead bodies!” “They are thrown everywhere!” “Silence!” 4 Hear this, you who trample on the needy and bring the poor of the land to an end, 5 saying, “When will the new moon be over, that we may sell grain? And the Sabbath, that we may offer wheat for sale, that we may make the ephah small and the shekel great and deal deceitfully with false balances, 6 that we may buy the poor for silver and the needy for a pair of sandals and sell the chaff of the wheat?” 7 The Lord has sworn by the pride of Jacob: “Surely I will never forget any of their deeds. 8 Shall not the land tremble on this account, and everyone mourn who dwells in it, and all of it rise like the Nile, and be tossed about and sink again, like the Nile of Egypt?” 9 “And on that day,” declares the Lord God, “I will make the sun go down at noon and darken the earth in broad daylight. 10 I will turn your feasts into mourning and all your songs into lamentation; I will bring sackcloth on every waist and baldness on every head; I will make it like the mourning for an only son and the end of it like a bitter day. 11 “Behold, the days are coming,” declares the Lord God, “when I will send a famine on the land—not a famine of bread, nor a thirst for water, but of hearing the words of the Lord. 12 They shall wander from sea to sea, and from north to east; they shall run to and fro, to seek the word of the Lord, but they shall not find it. 13 “In that day the lovely virgins and the young men shall faint for thirst. 14 Those who swear by the Guilt of Samaria, and say, ‘As your god lives, O Dan,’ and, ‘As the Way of Beersheba lives,’ they shall fall, and never rise again.”

Otou and Yumi Katayami are a couple in Nara, Japan. To look at them, you would have no idea anything was amiss. But, in reality, something was amiss indeed! Amazingly, Otou did not speak to his wife for twenty-three years. He continued to live with her and would respond to direct questions with grunts or nods, but he refused to speak to her. The reason? He was hurt, jealous at the attention that Yumi was giving the children and not him. So he decided to go silent. No words at all to his wife. For over twenty years! Recently, the children reached out to a Japanese television show in an effort to get the parents together so they might speak. And, amazingly, Otou did speak to his wife. He acknowledged how difficult their life must have been and told her he had been jealous of the children.[1]

Withholding one’s word, in human relationships, is cruel. Inevitably what lies behind it is what we just heard: hurt feelings, jealousy, bruised egos.

But in Amos 8 the Lord says that He is going to withhold His word, and His doing so is not a result of hurt feelings or a bruised ego. It is rather the result of Israel’s persistent wickedness, religious hypocrisy, and cruelty to the poor.

10 Then Amaziah the priest of Bethel sent to Jeroboam king of Israel, saying, “Amos has conspired against you in the midst of the house of Israel. The land is not able to bear all his words. 11 For thus Amos has said, “‘Jeroboam shall die by the sword, and Israel must go into exile away from his land.’” 12 And Amaziah said to Amos, “O seer, go, flee away to the land of Judah, and eat bread there, and prophesy there, 13 but never again prophesy at Bethel, for it is the king’s sanctuary, and it is a temple of the kingdom.” 14 Then Amos answered and said to Amaziah, “I was no prophet, nor a prophet’s son, but I was a herdsman and a dresser of sycamore figs. 15 But the Lord took me from following the flock, and the Lord said to me, ‘Go, prophesy to my people Israel.’ 16 Now therefore hear the word of the Lord. “You say, ‘Do not prophesy against Israel, and do not preach against the house of Isaac.’ 17 Therefore thus says the Lord: “‘Your wife shall be a prostitute in the city, and your sons and your daughters shall fall by the sword, and your land shall be divided up with a measuring line; you yourself shall die in an unclean land, and Israel shall surely go into exile away from its land.’”

In the fourth/fifth century, the church father John Chrysostom initially had a good relationship with Empress Eudoxia, the wife of the Emperor Arcadius. In time, the relationship between the powerful woman and the fiery preacher would deteriorate. John would preach against excesses and ostentation in feminine dress. He condemned and preached against obscene displays of wealth. He did not participate in the high life of the royal family. He would also thunder from the pulpit against the erection of a statue of Eudoxia near the cathedral. This, as you might imagine, did not make Eudoxia happy and she moved against him. There is a fascinating painting of Chrysostom the preacher locking horns with the Empress: she stands elevated above him as he addresses her from his pulpit.

Augustins – Saint Jean Chrysostome et l’Impératrice Eudoxie – Jean Paul Laurens 2004 1 156

Legend has it that this is how the exchange went when Eudoxia threatened to banish John Chrysostom.

“You cannot banish me, for this world is my Father’s house,” said John.

“But I will kill you,” the empress said.

“No, you cannot, for my life is hid with Christ in God.”

“I will take away your treasures,” said Eudoxia.

“No, you cannot, for my treasure is in heaven and my heart is there.”

“But I will drive you away from your friends and you will have no one left,” Eudoxia responded.

“No, you cannot,” said John, “for I have a Friend in heaven from whom you cannot separate me. I defy you. For there is nothing you can do to harm me.”[1]

The phrase “speaking truth to power” comes to mind here. Chrysostom had to set aside all fear and determine whether or not he would speak the truth regardless of what it would cost him.

Amos had to make the same decision.

So do you and I!

Matthew 24

15 “So when you see the abomination of desolation spoken of by the prophet Daniel, standing in the holy place (let the reader understand), 16 then let those who are in Judea flee to the mountains. 17 Let the one who is on the housetop not go down to take what is in his house, 18 and let the one who is in the field not turn back to take his cloak. 19 And alas for women who are pregnant and for those who are nursing infants in those days! 20 Pray that your flight may not be in winter or on a Sabbath. 21 For then there will be great tribulation, such as has not been from the beginning of the world until now, no, and never will be. 22 And if those days had not been cut short, no human being would be saved. But for the sake of the elect those days will be cut short. 23 Then if anyone says to you, ‘Look, here is the Christ!’ or ‘There he is!’ do not believe it. 24 For false christs and false prophets will arise and perform great signs and wonders, so as to lead astray, if possible, even the elect. 25 See, I have told you beforehand. 26 So, if they say to you, ‘Look, he is in the wilderness,’ do not go out. If they say, ‘Look, he is in the inner rooms,’ do not believe it. 27 For as the lightning comes from the east and shines as far as the west, so will be the coming of the Son of Man. 28 Wherever the corpse is, there the vultures will gather. 29 “Immediately after the tribulation of those days the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light, and the stars will fall from heaven, and the powers of the heavens will be shaken. 30 Then will appear in heaven the sign of the Son of Man, and then all the tribes of the earth will mourn, and they will see the Son of Man coming on the clouds of heaven with power and great glory. 31 And he will send out his angels with a loud trumpet call, and they will gather his elect from the four winds, from one end of heaven to the other.

It is one of the more famous translation errors to have entered the English vernacular. Smithsonian Magazine explains.

Henry Newman, an Anglo journalist working in Calcutta in the 1920s, first heard reports of a Wild Man on the slopes of the Himalayas from members of a 1921 British expedition to summit Everest led by Lieutenant Colonel C. K. Howard-Bury. Sherpas on the expedition discovered footprints that they believed belonged to the “wild man of the snows,” and word quickly spread through the Tibetans. Newman, hearing these reports, garbled the Tibetan term metoh kangmi (which means “man-like wild creature”), misrecognizing metoh as metch, and mistranslating “wild” as “filthy” or “dirty.” Settling finally on “The Abominable Snowman” for his English-speaking readers, the name stuck. Cryptozoologist Ivan Sanderson would later describe the impact of the name as being “like an explosion of an atom bomb,” capturing the imagination of schoolkids and armchair explorers all over Europe and America.

That is something, is it not? The Abominable Snowman is not, technically speaking, abominable after all…he is just wild! But the word stuck: “abominable.” Smithsonian Magazine continues with a really fascinating explanation of why that word is so jarring:

An abomination does more than evoke metaphysical horror and physical disgust; it is an affront to the ways in which we understand the world. Mary Douglas, in her 1966 anthropological classic, Purity and Danger, argues that one of the fundamental means humans have for understanding the world is to organize it into the “clean” and the “unclean”: religious rituals and prohibitions, taboo and transgression, all work to formalize these categories. But abominations, she writes, “are the obscure unclassifiable elements which do not fit the pattern of the cosmos. They are incompatible with holiness and blessing.” On the border between here and there, an abomination doesn’t just mark the limit of civilization, it troubles the boundaries themselves, it interrupts the categories we make to make sense of the world.[1]

That is so very well said. Abominations—things that are abominable—“are incompatible with holiness and blessing.”

Jesus will use the word in the Olivet Discourse, which we began journeying through with the beginning of Matthew 24. He uses the word but notes that it was used even before He used it, by Daniel.

Jesus says an abomination is coming.

Then He says that deceivers are coming.

But then He says, more significantly, that He is coming again!

In our consideration of these verses, we are not going to try to fit any overly-intricate prophetic scheme or chart or overall system. Rather, we are going to consider three movements that Jesus says will come: the coming of the abominable one, the coming of the deceitful ones, and the coming of the judging/saving One.

Amos 7

1 This is what the Lord God showed me: behold, he was forming locusts when the latter growth was just beginning to sprout, and behold, it was the latter growth after the king’s mowings. 2 When they had finished eating the grass of the land, I said, “O Lord God, please forgive! How can Jacob stand? He is so small!” 3 The Lord relented concerning this: “It shall not be,” said the Lord. 4 This is what the Lord God showed me: behold, the Lord God was calling for a judgment by fire, and it devoured the great deep and was eating up the land. 5 Then I said, “O Lord God, please cease! How can Jacob stand? He is so small!” 6 The Lord relented concerning this: “This also shall not be,” said the Lord God. 7 This is what he showed me: behold, the Lord was standing beside a wall built with a plumb line, with a plumb line in his hand. 8 And the Lord said to me, “Amos, what do you see?” And I said, “A plumb line.” Then the Lord said, “Behold, I am setting a plumb line in the midst of my people Israel; I will never again pass by them; 9 the high places of Isaac shall be made desolate, and the sanctuaries of Israel shall be laid waste, and I will rise against the house of Jeroboam with the sword.”

In 2016, Christianity Today published an article entitled, “Pay-to-Pray Scam: Christian Prayer Center Must Refund $7 Million.” This is beyond irritating to read.

For four years, anyone with a prayer request could pay the Christian Prayer Center (CPC)—a website with nearly 1.3 million Facebook fans—between $9 and $35 to intercede for them.

Visitors to the site (as well as its Spanish-language sister site, Oracion Cristiana) saw testimonials from religious leaders and laypeople who claimed that God gave them healthy babies, winning lottery tickets, money for mortgage payments, and clean HIV tests and cancer scans after they paid for prayer, according to the Washington State attorney general’s office.

More than 125,000 people did pay. From 2011 to 2015, their more than 400,000 transactions poured more than $7 million into the pocket of site creator Benjamin Rogovy.

The trouble was, the popular site—which eclipsed even the International House of Prayer in its Facebook following—was a fraud. A counter-Facebook page, the Christian Prayer Center Scam, went up in 2012.

The testimonials were fake. The photos of happy customers were stock footage. And “Pastor John Carlson,” who sent weekly emails and had a LinkedIn page, was made up. Correspondence was signed by the non-existent “Pastor Eric Johnston.”[1]

This is truly astonishing. There is something particularly obscene about greed and deceit masquerading as intercessory prayer. This is because of how powerful and beautiful intercession is. By intercession, we mean crying out to God on behalf of others. If the scoundrel in the news article above represents the corruption and blaspheming of intercessory prayer, then the prophet Amos in Amos 7 represents its flowering and beauty.

Let us consider what this amazing chapter reveals about the nature of judgment, the nature of intercession, and the heart of God.

Amos 6

1 “Woe to those who are at ease in Zion, and to those who feel secure on the mountain of Samaria, the notable men of the first of the nations, to whom the house of Israel comes! 2 Pass over to Calneh, and see, and from there go to Hamath the great; then go down to Gath of the Philistines. Are you better than these kingdoms? Or is their territory greater than your territory, 3 O you who put far away the day of disaster and bring near the seat of violence? 4 “Woe to those who lie on beds of ivory and stretch themselves out on their couches, and eat lambs from the flock and calves from the midst of the stall, 5 who sing idle songs to the sound of the harp and like David invent for themselves instruments of music, 6 who drink wine in bowls and anoint themselves with the finest oils, but are not grieved over the ruin of Joseph! 7 Therefore they shall now be the first of those who go into exile, and the revelry of those who stretch themselves out shall pass away.” 8 The Lord God has sworn by himself, declares the Lord, the God of hosts: “I abhor the pride of Jacob and hate his strongholds, and I will deliver up the city and all that is in it.” 9 And if ten men remain in one house, they shall die. 10 And when one’s relative, the one who anoints him for burial, shall take him up to bring the bones out of the house, and shall say to him who is in the innermost parts of the house, “Is there still anyone with you?” he shall say, “No”; and he shall say, “Silence! We must not mention the name of the Lord.” 11 For behold, the Lord commands, and the great house shall be struck down into fragments, and the little house into bits. 12 Do horses run on rocks? Does one plow there with oxen? But you have turned justice into poison and the fruit of righteousness into wormwood—13 you who rejoice in Lo-debar, who say, “Have we not by our own strength captured Karnaim for ourselves?” 14 “For behold, I will raise up against you a nation, O house of Israel,” declares the Lord, the God of hosts; “and they shall oppress you from Lebo-hamath to the Brook of the Arabah.”

When I was thirteen, the group Midnight Oil released their song “Beds are Burning.” Some of you may remember it. It is an arresting and memorable song with wonderfully odd lead vocals and a refrain that sticks in your head. The song is about (a) Aboriginal land rights in Australia and (b) the question of how a society that has wronged others can carry on in ease and celebration when people are suffering. Listen:

Out where the river broke

The bloodwood and the desert oak

Holden wrecks and boiling diesels

Steam at forty-five degrees

The time has come to say “Fair’s fair”

To pay the rent, to pay our share

The time has come, a fact’s a fact

It belongs to them, let’s give it back

How can we dance when our earth is turning?

How do we sleep while our beds are burning?

How can we dance when our earth is turning?

How do we sleep while our beds are burning?

The time has come to say “Fair’s fair”

To pay the rent now, to pay our share

Four wheels scare the cockatoos

From Kintore, east to Yuendemu

The Western Desert lives and breathes

In forty-five degrees

The time has come to say “Fair’s fair”

To pay the rent, to pay our share

The time has come, a fact’s a fact

It belongs to them, let’s give it back

How can we dance when our earth is turning?

How do we sleep while our beds are burning?

How can we dance when our earth is turning?

How do we sleep while our beds are burning?

The time has come to say “Fair’s fair”

To pay the rent now, to pay our share

The time has come, a fact’s a fact

It belongs to them, we’re gonna give it back

How can we dance when our earth is turning?

How do we sleep while our beds are burning?

The two repeated questions in the song are key:

How can we dance when our earth is turning?

How do we sleep while our beds are burning?

Indeed! How can we carry on as if nothing is wrong when others are suffering and suffering, to some extent, because of the behavior of the dominant society?

This is not the first time such a question has been asked. The prophet Amos asked the same questions. In particular, he too spoke of beds of and of revelry when people were suffering and hurting. In Amos 6, the Lord will phrase the question like this: How can you be “at ease in Zion” knowing what you have done and knowing the devastation it has wrought? How can you dance when the earth is turning? How can you sleep when your beds are burning? How can you be at ease in Zion when the cries of the suffering have reached the ears of God and judgment is coming upon you?

Let us unpack this powerful idea of being at ease in Zion. What does that mean? Furthermore, how do you know if you are at ease in Zion?

Matthew 24

1 Jesus left the temple and was going away, when his disciples came to point out to him the buildings of the temple. 2 But he answered them, “You see all these, do you not? Truly, I say to you, there will not be left here one stone upon another that will not be thrown down.” 3 As he sat on the Mount of Olives, the disciples came to him privately, saying, “Tell us, when will these things be, and what will be the sign of your coming and of the end of the age?” 4 And Jesus answered them, “See that no one leads you astray. 5 For many will come in my name, saying, ‘I am the Christ,’ and they will lead many astray. 6 And you will hear of wars and rumors of wars. See that you are not alarmed, for this must take place, but the end is not yet. 7 For nation will rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom, and there will be famines and earthquakes in various places. 8 All these are but the beginning of the birth pains. 9 “Then they will deliver you up to tribulation and put you to death, and you will be hated by all nations for my name’s sake. 10 And then many will fall away and betray one another and hate one another. 11 And many false prophets will arise and lead many astray. 12 And because lawlessness will be increased, the love of many will grow cold. 13 But the one who endures to the end will be saved. 14 And this gospel of the kingdom will be proclaimed throughout the whole world as a testimony to all nations, and then the end will come.

I must say, the Wikipedia article entitled “List of messiah claimants” is something to behold. Under the “Christian messiah claimants” heading, we find the following list of those who claimed to be Jesus or another Jesus or Jesus come again:

That is quite the list! And it is as predictable as it is lengthy and depressing. After all, Jesus told His disciples that precisely this would happen! He did so on the Mount of Olives in what we now call “The Olivet Discourse.” As we approach the Olivet Discourse, let us begin by noting the disposition that Jesus says His followers should have as we consider and approach the end of all things.

Amos 5:18–27

18 Woe to you who desire the day of the Lord! Why would you have the day of the Lord? It is darkness, and not light, 19 as if a man fled from a lion, and a bear met him, or went into the house and leaned his hand against the wall, and a serpent bit him. 20 Is not the day of the Lord darkness, and not light, and gloom with no brightness in it? 21 “I hate, I despise your feasts, and I take no delight in your solemn assemblies. 22 Even though you offer me your burnt offerings and grain offerings, I will not accept them; and the peace offerings of your fattened animals, I will not look upon them. 23 Take away from me the noise of your songs; to the melody of your harps I will not listen. 24 But let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream. 25 “Did you bring to me sacrifices and offerings during the forty years in the wilderness, O house of Israel? 26 You shall take up Sikkuth your king, and Kiyyun your star-god—your images that you made for yourselves, 27 and I will send you into exile beyond Damascus,” says the Lord, whose name is the God of hosts.

Hypocrisy is alive and well in our culture, and when it couples with religion it gives birth to particularly ugly offspring. The Southern Baptist Convention, of which we are a part, has certainly seen its share of examples in recent days.

Now I ask you: Does this represent the majority of Southern Baptists? Absolutely not. Why, then, do such cases get such attention? For this reason: the world knows that sin exists, but what it finds particularly stupefying is how such blatant atrocities exist among those who are ostensibly leaders in the body of Christ. We invite this kind of scrutiny by claiming to be the people of God.

In other words, even the world knows that there is something particularly heinous about religious hypocrisy, especially religious moral hypocrisy or religious criminal hypocrisy.

In a weird way, the world’s shock and even the lost world’s glee at religious hypocrisy is a compliment to the church, for behind it is the idea that if there is a God and if we are His people then our lives really should look different. No, not perfect, but different nonetheless. Is it not so? Should those who have professed allegiance to Jesus Christ not have lives that are least striving to be different, to be holy?

One atheist writer, in his expose of a recently-fallen Christian apologist, wrote this:

I consider it fair fighting to suggest that if Christianity were true, Christians would be different. The religion’s official documents speak mightily of the sanctifying power of the blood of Jesus. This is one of the few testable claims Christianity makes. If being a “new creature” in Christ means anything, it means being significantly different from us old creatures. If Jesus really sanctifies we should see more than mere anecdotes about lost wretches getting found; we should see vast differences between God, Inc. and Tobacco, Inc…

Thoughtful readers will spare me the “Christians aren’t perfect, just forgiven” straw man. No skeptic worth her salt considers the absence of perfect Christians to be evidence against the truth of the religion. The claim is, rather, that if Christianity were true, Christians would be noticeably different around the things that matter, like money and integrity in business. They aren’t. Therefore, . . .[1]

Let us talk about hypocritical religion, but which term I mean this: A self-deluding practice in which there is a chasm between the externals of religious observance and the internal realities of the practitioner’s rebellious heart.

**On Sunday, September 17, 2023, Central Baptist Church held its worship service as well as its church picnic off-campus, under the pavilion at Sherwood Forest in Sherwood, Arkansas. After a wonderful time of singing and a number of testimonies, I shared the following ten reasons why I thought the devil hated our “Love, Central” weekend of mission and celebration. The ten reasons and supporting passages are listed below, but you can hear the actual message in the last 15-ish minutes of this audio clip.**

Luke 10

17 The seventy-two returned with joy, saying, “Lord, even the demons are subject to us in your name!” 18 And he said to them, “I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven.”

James 1

22 But be doers of the word, and not hearers only, deceiving yourselves. 23 For if anyone is a hearer of the word and not a doer, he is like a man who looks intently at his natural face in a mirror. 24 For he looks at himself and goes away and at once forgets what he was like. 25 But the one who looks into the perfect law, the law of liberty, and perseveres, being no hearer who forgets but a doer who acts, he will be blessed in his doing.

1 Peter 3

8 Finally, all of you, have unity of mind, sympathy, brotherly love, a tender heart, and a humble mind.

John 8

44 You are of your father the devil, and your will is to do your father’s desires. He was a murderer from the beginning, and does not stand in the truth, because there is no truth in him. When he lies, he speaks out of his own character, for he is a liar and the father of lies.

Luke 22

31 “Simon, Simon, behold, Satan demanded to have you, that he might sift you like wheat,

Luke 15

7 Just so, I tell you, there will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous persons who need no repentance.

Revelation 12

10 And I heard a loud voice in heaven, saying, “Now the salvation and the power and the kingdom of our God and the authority of his Christ have come, for the accuser of our brothers has been thrown down, who accuses them day and night before our God.

Romans 10

14 How then will they call on him in whom they have not believed? And how are they to believe in him of whom they have never heard? And how are they to hear without someone preaching? 15 And how are they to preach unless they are sent? As it is written, “How beautiful are the feet of those who preach the good news!”

Luke 10

17 The seventy-two returned with joy, saying, “Lord, even the demons are subject to us in your name!” 18 And he said to them, “I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven.

Philippians 2

5 Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus, 6 who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, 7 but emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. 8 And being found in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross.