I know the names of my ancestors’ slaves.

How many people can say that? I can.

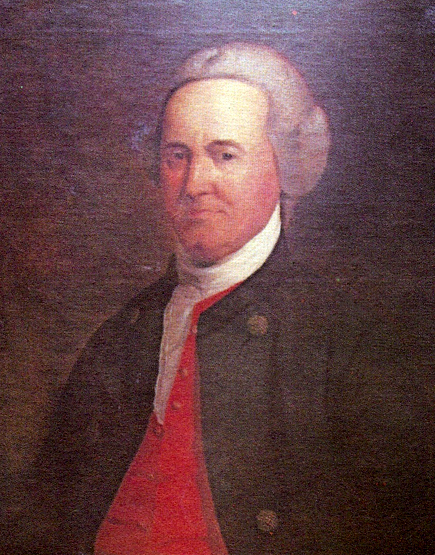

The last will and testament of Revolutionary War Brigadier General Richard Richardson was signed in 1780, the year he died. I stand in direct paternal lineage to Richard Richardson. He is truly my Grandfather, times about 6. There’s a monument to him on the statehouse grounds in Columbia, SC, 2 or 3 miles from where I was born at Richland Memorial Hospital. Heck, Main Street in Columbia used to be called Richardson Street after my Grandfather. Every now and again, when we return to my hometown, some of us will drive out to Rimini (about 25 minutes from my parents’ house but less than ten miles from the old homes of my immediate grandparents, all but one of whom have passed on), and see his tomb there on the grounds where the grand old Richardson house once stood: Big Home Plantation, as it was known.

And when we go we also look over at the grave of General Richardson’s beloved horse Snowdrop. Richard Richardson put up a stone for his horse.

I am in many ways proud of my Grandfather. He fought for the patriot cause of freedom and led the Snow Campaign to squelch the loyalist cause in the backcountry of South Carolina. The legend is that the British Col. Tarleton (a pox be upon his memory) had my Grandfather’s sons exhume his body from the grave so that he could see, he said, the man who had eluded him for so long. I like these stories. I like the romance and legend and history of these stories. I realize that in many ways my life is better because of the actions of Richard Richardson.

And yet…

He fought for freedom, but he owned slaves.

I do not know where their headstones are. Were any put up? I know where his horse is buried. I do not know where his slaves are buried. But I know their names. They are listed in his last will and testament as follows:

IN PRIMUS, I give and bequeath to my well beloved wife, Dorothy Richardson, the thirty-four following Slaves or Negroes (vis) Tom the Carpenter, Judy, Ned & Agar, his wife & 2 children, Tommy, Thisby, Tommy & Fally, Devonshire, Nanny, Paul, Qui, London, Silcey, Moses, Fam, Tohan, Kate, Peter, Peggy, Jack, Pollipus, Balliss, Billy, Stump, Phebe, Gabriel, Phebe, Rachel, John, Priscilla, Fusy, Judah, Balina with their and each of their Issue & Increase…

And later:

I give and bequeath to my beloved daughter, Susannah, my beloved sons—James Burchell, John Peter, Charles and Thomas Richardson, ten Negroes each, to be of equal value and worth with the use given to my other children, and the remaining part of my Negroes to be equally divided between my nine children and that my beloved daughter, Susannah, have the following ten Negroes, being the Tenth part allotted as above (viz) Sarah, Cyrus, Peter, Juky, Jefe, Hancel, Nill Beck, Home, Toby and Jack’s Creek Betty with their future Increase.

And later:

I give and bequeath the rest and residue of my lands to my beloved sons, John Peter, Charles, and Thomas Richardson, to be divided in equal valuation between them, unless my wife should prove pregnant, in such case (if it should prove a Son) then he shall be entitled to an equal part of lands with the three last mentioned and ten Negroes & an equal part of the Surplus…

And, again, later, near the end of the will, because he apparently forgot, he came back around to what he bequeathed his wife, Dorothy, my grandmother:

I give and bequeath to my dearly beloved wife, Dorothy Richardson, one more Slave, named Mulattoe Bob, the weaver, besides those before mentioned…

And there it is. Doled out alongside his featherbeds and sword and buckles and horses and land are his slaves. Handed out. Divvied up. And I ask myself this: If my Great Grandfather’s actions against the loyalists shaped my life for the positive did my Great Grandfather’s actions against Judy, Ned & Agar, his wife & 2 children, Tommy, Thisby, Tommy and Fally, Devonshire, Nanny, Paul, Qui, London, Silcey, Moses, Fam, Tohan, Kate, Peter, Peggy, Jack, Pollipus, Balliss, Billy, Stump, Phebe, Gabriel, Phebe, Rachel, John, Priscilla, Fusy, Judah, Balina, Sarah, Cyrus, Peter, Juky, Jefe, Hancel, Nill Beck, Home, Toby and Jack’s Creek Betty with their future Increase, and “Mulattoe Bob” shape my life for the negative?

The Past That is Not Past

If my experience of freedom is causally connected to my Grandfather’s militaristic efforts 240ish years ago, is my experience of race and racism likewise connected to his owning slaves? Can I have one without the other?

We all live in the tension of what shaped us and what we are trying to become. 240 years ago my Grandfather owned slaves. Many slaves. How did he treat them? I have no idea. No specific anecdotal evidence has come down, at least that I am aware of. But I know this: however he treated them, he treated them, by definition, as slaves. And I also know this: the descendants of those slaves try to think back to their ancestors just as I do to mine. Our efforts at remembering are similar in their desire to know but very different in what they discover.

Does such a thing curse the generations that follow? Are the sins of the father passed to the sons over 240 years?

We are responsible for our own actions, to be sure, but we are shaped by the actions of everything that came before us. I am the descendant of slave owners. Am I thereby guilty? I don’t know. But I am certainly thereby shaped. Necessarily so. Undeniably so. That is how life works. In ways both practical and seemingly mystical we are, to a very real extent, the result of the actions of those who came before. Am I materially shaped by it? Probably in ways I do not know, yes. Psychologically? Spiritually? Certainly so. Has our society been systemically shaped by it? It would be hard to say that it has not been.

When people talk about systemic racism, about racist structures, about unspoken assumptions of prejudice woven into the very tapestry of modern life, some object. “That cannot be,” they say. “How can hatred be systemic? Isn’t hatred limited to actions? Even if it can be shown to be systemic at a given point in time, surely such hatred is purged from our systems by now, right?”

What do I think? I think that 240 years is actually not a very long time. At all. I think this is something that those who think we’ve “moved past” racism need to understand. Time is much, much shorter than we think. Ryan Holiday writes:

It’s sad how disconnected from the past and the future most of us really are. We forget that woolly mammoths walked the earth while the pyramids were being built. We don’t realize that Cleopatra lived closer to our time than she did to the construction of those famous pyramids that marked her kingdom. When British workers excavated the land in Trafalgar Square to build Nelson’s Column and its famous stone lions, in the ground they found the bones of actual lions, who’d roamed that exact spot just a few thousand years before. Someone recently calculated that it takes but a chain of six individuals who shook hands with one another across the centuries to connect Barack Obama to George Washington. There’s a video you can watch on YouTube of a man on a CBS game show, “I’ve Got a Secret,” in 1956, in an episode that also happened to feature a famous actress named Lucille Ball. His secret? He was in Ford’s Theatre when Lincoln was assassinated. England’s government only recently paid off debts it incurred as far back as 1720 from events like the South Sea Bubble, the Napoleonic wars, the empire’s abolition of slavery, and the Irish potato famine—meaning that in the twenty-first century there was still a direct and daily connection to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. (Ego is the Enemy, p.141-142)

Did you hear that? “In the twenty-first century there was still a direct and daily connection to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.”

In his 1950 story, Requiem for a Nun, William Faulkner wrote, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

This is true. Try and deny it.

So when Derek Chauvin put his knee on the neck of George Floyd for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, killing him, murdering him, he was not doing something in some detached vacuum from all of the racial horrors that have gone on before. He too was shaped by all that came before him and all that is around him, maybe in ways he does not even realize or understand.

My point? Systemic racism as a concept must refer not merely to the organizational and governmental structures that define our particular moment; it must also be allowed to refer to the spiritual and psychological systems of which we are the inheritors and which stand in much closer existential proximity to us than many detractors want to acknowledge.

This is why people are angry: they see this and understand it.

The past is never dead. It’s not even past.

This is why people are protesting.

They see in modern society the demonic flowering of seeds sown in the past-that-is-ever-present. They do not see a mere action so it does no good to say, “A bad man did a bad thing and has been arrested.” No actions are mere actions. They see, not without reason, a system and a mindset that is part of our national psyche, part of our national soul. The actions are not distinct from the milieu that gave rise to them.

And not only do they see it, I see it. And I detest it. And I gladly join my voice to those condemning it.

Does the past-not-being-past mean that change cannot happen? No, it does not mean that. We can change. It just means that change does not happen when you view the past as something “back there” on which you have shut a door and over which you have washed your hands. Change happens when you take an unflinching look at the present-ness of the past and determine to understand it, name it, see how you are the inheritor of it, and then boldly deviate it from here and now.

We change not because the past is past but because while standing in the ever-flowing river of the past-becoming-present we determine that we would like this present moment to become the past of the future that looks very very different than the past that is our present! (You might want to re-read that one.)

The extent to which the race issue and reality is better is directly correlated to men and women who have understood and acted in this realization: that we must own the past in its ugliness and alter it through hard work in the present.

The Church

May I be allowed one more William Faulkner quote? In 1956 Faulkner wrote an essay entitled “On Fear: Deep South in Labor: Mississippi.” In this essay, Faulkner is describing the many voices that were trying to speak to the issue of race in the South. He cites the voices of senators, circuit judges, ordinary citizens, etc. He then wrote this:

There are all the voices in fact, except one. That one voice which would adumbrate them all to silence, being the superior of all since it is the living articulation of the glory and the sovereignty of God and the hope and aspiration of man. The Church, which is the strongest unified force in our Southern life since all Southerners are not white and are not democrats, but all Southerners are religious…Where is that voice now?…Where is that voice now, which should have propounded perhaps two but certainly one of these still-unanswered questions?

1. The Constitution of the U.S. says: Before the law, there shall be no artificial inequality—race, creed or money—among citizens of the Unites States.

2. Morality says: Do unto others as you would have others do unto you.

3. Christianity says: I am the only distinction among men since whosoever believeth in Me, shall never die.

Where is this voice now, in our time of trouble and indecision? Is it trying by its silence to tell us that it has no validity and wants none outside the sanctuary behind its symbolical spire?” (William Faulkner: Essays, Speeches & Public Letters, p.92-106).

Faulkner, himself not a Christian, not only marveled at the silence of the church, he also saw the radical disjunction between the Church’s silence and the resources inherent in the creed in which the church professed to believe!

This stings me. A non-Christian had to tell Christians that the Church really does have a confession that could address and resolve the stain of racism if the Church were to truly embrace and live out its confession!

Faulkner was right. The gospel he rejected in his own life is indeed a gospel that contains the light and healing that we need.

Jesus, even given the Church’s frequent failure to follow Him, is still the answer.

I have debated on whether or not to say anything about all of this. I have not been shy in addressing racism from the pulpit, but I usually try to keep my social media and online presence clear of controversy. That’s an intentional decision. But I have decided that I need to say something now. And here is what I would like to say:

Racism is a hellish evil that must be rooted out and rejected for what it is.

Racism is systemic in ways that those who do not want to admit this likely do not realize.

George Floyd was murdered and his murderers should be tried accordingly.

But What About…

Some of my readers will want to add caveats.

What about good cops? Yes, good cops, of which there are many, should not be smeared by the actions of bad cops even if the structures and systems of law enforcement are critiqued. We have amazing members of law enforcement in our church who love the Lord and want to honor the badge and who rightly, like so many policemen and women, denounce racism and all forms of police brutality. I am grateful for the many men and women who honor the uniform and risk their lives daily for the betterment of our society. I can sit here right now and think of law enforcement personnel in our church who span the racial spectrum: black, hispanic, caucasian. I know their hearts. They in no way condone what happened to George Floyd. It would be obscene to mention them or their peers alongside bad cops who do wicked things.

What about instances of black-on-white crime? All instances of violence and murder should be condemned as demonic and wicked.

Don’t all lives matter? Of course they do.

Does this make looting, violence, and the destruction of property ok? Looting, violence, and destruction of property should be condemned, even as the right to peaceful, passionate protest should be defended.

But here’s the thing: the murder of George Floyd is one of many recent shocking acts that expose the moral rot of racism that many people experience in their daily lives and which many of us will never experience. You can stand in this moment of clarity and outrage and speak to this reality without the subtle protest of endless qualification. It is ok to be outraged at this reality. Doing so does not mean you are betraying other realities that equally deserve outrage.

A few years ago when I preached on abortion I did not have any church members saying, “But what about poverty! But what about corporate greed! But what about…etc. etc.”

We are adept at addressing issues without dragging in all other issues unless the issue being addressed makes us uncomfortable. Racism is the issue on the table. Let us let it be the issue.

It is possible to hate evil in all of its manifestations and yet realize that particular moments call for denunciations of particular evils.

You can say “Black Lives Matter” as a simple statement of truth without having to say everything or anything else. In fact, saying something else when this is the particular issue at hand will feel to many like an effort to silence very real pain and hurt. Black lives do matter. Period. Full stop.

Conclusion

I am the descendant of slave owners. I must strive to understand how that has shaped my unseen world of assumptions and presuppositions. But as the descendant of slave owners I can repudiate their ownership of slaves and learn from their deep and wicked sins so as not to commit and perpetuate my own. In so doing, I can help shape a new past that will be present in the future. In so doing we become agents of change.

I do repudiate my Grandfather’s ownership of slaves.

I do want to understand the ways in which my past has shaped me.

I do want to love all people just as all people are loved by the Lord God.

God help me to do so.

Written in 2012, Richards’ and O’Brien’s [R&O hereafter]

Written in 2012, Richards’ and O’Brien’s [R&O hereafter]  Brandon O’Brien’s

Brandon O’Brien’s