Matthew 27

62 The next day, that is, after the day of Preparation, the chief priests and the Pharisees gathered before Pilate 63 and said, “Sir, we remember how that impostor said, while he was still alive, ‘After three days I will rise.’ 64 Therefore order the tomb to be made secure until the third day, lest his disciples go and steal him away and tell the people, ‘He has risen from the dead,’ and the last fraud will be worse than the first.” 65 Pilate said to them, “You have a guard of soldiers. Go, make it as secure as you can.” 66 So they went and made the tomb secure by sealing the stone and setting a guard.

Matthew 28

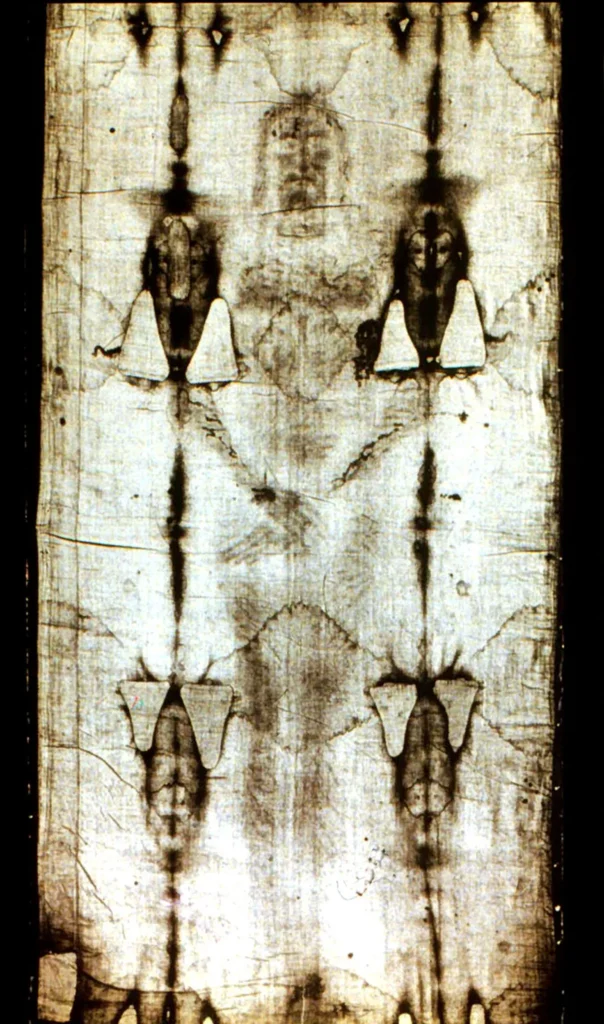

1 Now after the Sabbath, toward the dawn of the first day of the week, Mary Magdalene and the other Mary went to see the tomb. 2 And behold, there was a great earthquake, for an angel of the Lord descended from heaven and came and rolled back the stone and sat on it. 3 His appearance was like lightning, and his clothing white as snow. 4 And for fear of him the guards trembled and became like dead men. 5 But the angel said to the women, “Do not be afraid, for I know that you seek Jesus who was crucified. 6 He is not here, for he has risen, as he said. Come, see the place where he lay. 7 Then go quickly and tell his disciples that he has risen from the dead, and behold, he is going before you to Galilee; there you will see him. See, I have told you.” 8 So they departed quickly from the tomb with fear and great joy, and ran to tell his disciples. 9 And behold, Jesus met them and said, “Greetings!” And they came up and took hold of his feet and worshiped him. 10 Then Jesus said to them, “Do not be afraid; go and tell my brothers to go to Galilee, and there they will see me.”

Some years back, the philosopher and theologian David Bentley Hart published a list of his favorite fiction books. Among them was The Blind Owl by the Iranian author Sadegh Hedayat. It is a strange an interesting book. In it, the protagonist reflects from his sickbed on his disinterest in religion and in God.

Several days ago she brought me a prayer book that had a layer of dust on it—not only had I no use for a prayer book, but likewise no sort of rabble book, writing, or idea had any use for me. What use had I for their lies and nonsense, was not I, myself, the product of a long line of past generations and were not their inherited experiences found in me, was not the past in my being?—But none of this has ever had any effect on me: neither mosque, nor the call of the muezzin, nor ablutions and spitting, and bending over and standing upright before an almighty god with absolute power that one has to converse with in Arabic. Beforehand, when I was healthy, if I several times obligatorily went to the mosque and tried to harmonize my heart with those of others, inevitably my eyes would wander and stare at the glazed tiles and the forms and patterns of the walls of the mosque, transporting me to the realm of pleasant dreams, and in this way I would find a means of escape for myself—During prayer I would close my eyes and hold my palms in front of my face—in this night that I had created for myself, like the words they unconsciously repeat while sleeping, I would pray, but the utterance of these words was not from deep within my heart, for I would much rather talk to a friend or an acquaintance than with God, with Almighty God! For God was too much for me.

Whilst lying in a warm and damp bed, all of these issues were not worth more than a grain of barley to me, and at these times I did not want to know whether a God truly existed or if it was an object the rulers on earth have conceived to consolidate their divine station and ravage their subjects—to reflect the images on earth onto the sky—I only wanted to know whether or not I would make it through the night until the next morning—Confronted with death, I sensed how weak and childish were religion, faith and belief, almost a kind of diversion for healthy and fortunate persons—Confronted with the horrifying actuality of death and the suffering that I went through, all that they had inculcated in me about reward and punishment of the soul and the Day of Resurrection had become an insipid lie, and when confronted with the fear of death the prayers that they had taught me had no effect.—[1]

This strikes me as tragic and heartbreaking: a sick man scoffing at the idea of resurrection, seeing it as “an insipid lie” that had “no effect” on him when confronted “with the fear of death.”

Hedayat himself was a talented but tragic figure. Consider his passing:

In 1951, overwhelmed by despair, Hedayat left Tehrān and traveled to Paris, where he rented an apartment. A few days before his death, Hedayat tore up all of his unpublished work. On 9 April 1951, he plugged all the doors and windows of his rented apartment with cotton, then turned on the gas valve, committing suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning. Two days later, his body was found by police, with a note left behind for his friends and companions that read, “I left and broke your heart. That is all.”[2]

He was 48 years old when he took his own life.

I do not claim to know all that was going on in Hedayat’s life, but it does strike me that trust in a good God and in the reality of life after death and in the reality of resurrection could have helped him immensely.

Indeed, the resurrection of Jesus is presented in scripture as the antidote to despair: the despair of the disciples when confronted with the reality of death and the despair of the world at large when confronted with the same. At the end of Matthew 27 and the beginning of Matthew 28, we find the powers seeking to stop the resurrection from taking place…and failing miserably in their attempt. And we may thank God for this!

Continue reading →