***Spoiler Alert: While I have tried not to give away key developments in the book, there are one or two spoilers in this review.***

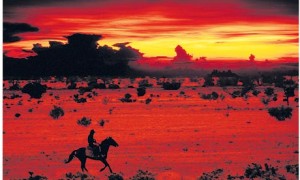

Cormac McCarthy, the undisputed heir of Faulkner, won the Pulitzer Prize for Blood Meridian: Or the Evening Redness in the West. It is not hard to see why. The book is jarring, disturbing, stunning, and provocative in the ways that great literature should be.

Cormac McCarthy, the undisputed heir of Faulkner, won the Pulitzer Prize for Blood Meridian: Or the Evening Redness in the West. It is not hard to see why. The book is jarring, disturbing, stunning, and provocative in the ways that great literature should be.

The book tells of the (non-fictional) mid-19th century Glanton Gang: a group of Americans under the leadership of soldier John Joel Glanton who were hired by concerned Mexicans to hunt down and destroy violent bands of Apaches. Glanton and his posse descended into a kind of crazed bloodlust and debauchery in the process that led them to kill and scalp not only Apaches but also peaceful Indians, Mexicans, and, basically, whomever got in their way.

This is perfect grist for the mill of Cormac McCarthy who, perhaps more than any other writer, has made the careful and prophetic exploration of human weakness and evil the core of his literary corpus for many years now. In his hands, the story of Glanton and his posse becomes a hellish and nightmarish debacle of human avarice and ignominy. Glanton is depicted as ruthless and nearly demonic, but he does not hold a candle to the Judge, who, in the story, is a massive, hairless, brilliant, philosophizing, amoral, vicious, cunning tyrant. The only character on which the reader can possibly attempt to attach any sympathy is the Kid, though he too has hands stained with blood. The point at which we attempt to attach sympathy to him is in his revulsion at the Judge and his understated awareness that the Judge is “crazy.”

McCarthy is a master at pointing out the nihilistic hubris of man detached from God and meaning and transcendence. The Judge is a kind of walking metaphor for human self-deification and, specifically, violence (at least as I saw him). I was reminded of the words of the South Carolina mass murderer Peewee Gaskins who said that when he killed people he became God in that instance, having the power of life and death.

In terms of his writing, McCarthy takes things to a whole new level here. My goodness: his descriptions of landscapes, atmospheres, and topography are stunning and utterly evocative. His vocabulary can soar to dizzying heights or hit you in the guts with understated ferocity. I.e.:

When they entered Glanton’s chamber he lurched upright and glared wildly about him. The small clay room he occupied was entirely filled with a brass bed he’d appropriated from some migrating family and he sat in it like a debauched feudal baron while his weapons hung in a rich array from the finials. Caballo en Pelo mounted into the actual bed with him and stood there while one of the attending tribunal handed him at his right side a common axe the hickory helve of which was carved with pagan motifs and tasseled with the feathers of predatory birds. Glanton spat.

Hack away you mean red n—–, he said, and the old man raised the axe and split the head of John Joel Glanton to the thrapple.

Man. Just man!

Is Blood Meridian for everybody? I think not. It is very violent and very dark. But I daresay that those who know what McCarthy is attempting to do, and those who would like to consider a brilliant depiction of a little-known and tragic incident in American history, will find this book memorable and unsettling and though-provoking.

What an astounding, brutal, masterful book.