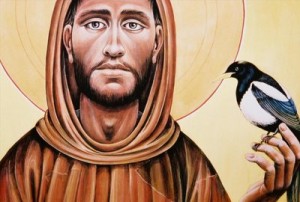

From June 6-7, a number of men from Central Baptist Church, North Little Rock, spent time in a retreat at Subiaco Abbey in Subiaco, Arkansas. This was the first of what I intend to be annual “Mighty Men of God” retreats in which men consider the lives of great men from Christian history. This year we considered the life of Francis of Assisi and what his example can show us about what it means to follow Jesus. To that end, I put together a workbook highlighting four episodes from Francis’ life. I am providing the Leader’s Guide of the workbook here, as a pdf. I hope it encourages and challenges you.

From June 6-7, a number of men from Central Baptist Church, North Little Rock, spent time in a retreat at Subiaco Abbey in Subiaco, Arkansas. This was the first of what I intend to be annual “Mighty Men of God” retreats in which men consider the lives of great men from Christian history. This year we considered the life of Francis of Assisi and what his example can show us about what it means to follow Jesus. To that end, I put together a workbook highlighting four episodes from Francis’ life. I am providing the Leader’s Guide of the workbook here, as a pdf. I hope it encourages and challenges you.

Tag Archives: monasticism

Nancy Klein Maguire’s An Infinity of Little Hours

“But monks are dumb!” The comment was made in the midst of a Wednesday night prayer meeting discussion in which, somehow, the issue of monasticism had come up. The lady who said it meant it with all the genuine sincerity of a cradle-Baptist who, for the life of her, could not see any merit whatsoever in the very idea of monasticism. The comment was undoubtedly buttressed by a strong dose of anti-Catholic sentiment and perhaps even by the Luther movie I had showed some months earlier to celebrate Reformation Day. After all, Luther’s vow to St. Anne had proven to be an act of fear-driven works righteousness, so the whole enterprise must be absurd, right?

I gently pointed out that calling every aspect of monasticism “dumb” was perhaps unwise, especially given the crucial role that monasticism has played in preserving and transmitting the Bible. But in my mind I had a much more visceral reaction to such a statement. Dumb? Really? And the average Southern Baptist minister is what exactly? A paragon of virtue, wisdom, and Christ-likeness? And what of the laity? What of the whole comfortable, American, Evangelical enterprise? What would we call it?

Monasticism is not without its problems. I agree with Bonhoeffer’s diagnosis in Discipleship that when the church set apart men and women who were to give all for the gospel, it inadvertently excused the cultural accomodationism that the majority of those within the church had fallen into (i.e., “Well, after all, we’re not monks!”) But perhaps that objection also states the great virtue of monasticism: it reminds us, in sometimes shocking and uncomfortable ways, that (to borrow from Kuyper) “there’s no square inch of reality over which Christ doesn’t say ‘Mine!’” As such, monasticism has a prophetic role to play in the Church.

An Infinity of Little Hours is a spellbinding chronicle of 5 young men’s attempts to join the rigid Carthusian order. The Carthusians have recently been given a great deal of attention, most compellingly through Philip Groening’s “Into Great Silence,” a project that was ironically finished just a few months before Maguire’s book. While this book lacks the overall spiritual, emotional, and psychological punch that Groening’s haunting documentary provides, it is right up there with it.

Maguire’s book is a profoundly beautiful and a powerful work of art. It is immensely educational. It draws the reader into the inner workings of an order that most people throughout Christian history have known very little about.

The Carthusians are fond of their motto: “Never reformed because never deformed.” While the reality undermines this sentiment somewhat, it is by-and-large true that this order of monks have remained amazingly unchanged throughout their long and rich history.

The book follows the journey of five young men from 1960 to 1965. Each came to the order seeking nothing less than God Himself. Not surprisingly, most of these five were strongly influenced by Merton’s Seven Story Mountain. Only one of the five would ultimately remain with the Carthusians, but all five had their lives indelibly marked by their fascinating, demanding, and daunting journey in the order.

What strikes the reader more than anything else is the challenge of solitude that each of these men faced. The Carthusians spend the majority of their time in their cells, essentially small houses. Their lives are dominated by the monastic hours that call them every day, time and time again, to corporate prayer and to choir. Hearing of the various men’s struggles with learning how to sleep only a few hours at a time was fascinating and made me seriously question whether or not I would ever be able to do such a thing.

Maguire’s book is sympathetic. Perhaps it is because she is married to an ex-Carthusian. She has no desire to ridicule this life that must appear ridiculous to many observers. She depicts the Carthusians as men who are passionate about knowing God and see in the monastic impulse a powerful tool for doing just that.

To be sure, her depiction is not overly-romanticized. She shows the political wrangling within the order, the ambition that occasionally grips the monks, and the inner conflicts and tensions that plague all human relationships at times. Her chapter on the conflicts in the choir was humorous and fascinating.

The book will undoubtedly leave the Protestant reader with some problems. The most fundamental problem with this attempt at living the Christian life is its stifling legalism. I’m almost hesitant to mention this, because American Evangelicals tend to call almost any attempts at mortifying the flesh “legalistic.” To be sure, we have a perverse understanding of “freedom” that borders on antinomianism. But the fact remains that monastic expressions like the Carthusian order have a stifling measure of legalism under which even the majority of their own applicants eventually wither.

I was moved by the pitiful fact that more than a few Carthusians collapse under the psychological strain of the order. Than neither proves nor disproves anything, of course, for many SBC pastors collapse under the stress of the ministry as well! The book does reveal that some of the more excessive aspects of the aestheticism of the Carthusians are being softened a bit. Showers have been installed in some of the monasteries (with no hot water, of course), and a few other things along those lines.

I was also struck by the fact that two of the five young men that Maguire chronicles eventually left the order and embraced the homosexual lifestyle. There is no evidence that homosexual practices occur in the order itself, but the anecdotal evidence provided by Maguire would suggest that perhaps monasticism (and the priesthood itself?) attracts men who are trying to overcome their own demons.

In all, however, I am very glad to have read this book. I would recommend it (cautiously) as a fascinating look at a unique movement. There are aspects of this movement that must be rejected. But I daresay there are aspects that would strengthen the devotional life of the average Evangelical in powerful ways.

Read this book.

Thomas Merton’s The Wisdom of the Desert

My knowledge of the Desert Fathers has heretofore been restricted to some shocking examples of asceticism-run-amuck cited in Dallas Willard’s Spirit of the Disciplines and a single issue of Christian History magazine. I’ve had some hazy concepts of St. Anthony battling demons and of Simon Stylite sitting on top of a column for way too long in some heroic but misguided attempt at mortifying the flesh. My understanding of these fascinating people was in desperate need of some balance and perspective. And so, on a recent and rare day off, I found myself driving to the picturesque Callaway Gardens for a day of walking the woods in solitude and in the hope of enjoying some rest. I soon found myself seated in the unbelievably beautiful “thin place” of the Callaway Gardens chapel (which is – I kid you not – about as close to Rivendell as we have on this earth) with a copy of Thomas Merton’s The Wisdom of the Desert in my hand. When I stood up to leave, I had finished this amazing little work and I knew I would be forever changed.

The Wisdom of the Desert is a collection of (mainly brief) sayings from the desert fathers. The introductory essay by Merton is illuminating and strangely moving. Merton argues that the desert fathers have been wrongly maligned as anti-social and fanatics. He persuasively argues that instead of being anti-social, they were looking instead for authentic society (thus the presence of sayings that the abbots passed on to one another and to the brethren), and that instead of being fanatics, they were simply intensely focused on living the crucified life.

Merton has hit the mark, and I daresay that I will be more cautious the next time I am tempted to laugh off these men who retreated from the world. What, after all, is true society and authentic relationship? What if, after all, our uncritical immersion in the crumbling pagan polis not only isn’t true society but renders such essentially impossible?

Merton presents these sayings, then, not in an effort to call for a literal repetition of the particulars of the Desert Fathers’ circumstances, but rather so that we might be moved to know and, in so many ways, live the life they so admirably modelled.

The sayings themselves are pithy, concise, and brimming over with wisdom. Merton attributes this brevity to the humility of the Fathers and the fact that the closer we come to God, the less gregarious we inevitably become.

Some of the consistent themes of this selection of sayings are anger, gluttony, humility, and control of the tongue. The sayings are frequently winsome, occasionally humorous, and inevitably inspiring.

A few of my favorites:

“It was said of Abbot Agatho that for three years he carried a stone in his mouth until he learned to be silent.” (XV)

“Abbot Ammonas said that he had spent fourteen years in Scete praying to God day and night to be delivered from anger.” (XXIV)

And my hands-down favorite:

“Abbot Lot came to Abbot Joseph and said: Father, according as I am able, I keep my little rule, and my little fast, my prayer, meditation and contemplative silence; and according as I am able I strive to cleanse my heart of thoughts: now what more should I do? The elder rose up in reply and stretched out his hands to heaven, and his fingers became like ten lamps of fire. He said: Why not be totally changed into fire?” (LXXII)

I like that. I like it a lot. It reminds me of T.S. Eliot’s, “Do I dare disturb the universe?” Or perhaps John Wesley’s, “If I had 300 men who feared nobody but God and hated nothing but sin and were determined to have nothing known among men but Christ and him crucified, I could set the world on fire.” Or the anonymous, “When God sets a man on fire, people will show up to watch him burn.”

On and on it goes in all of its wonderful proverbial glory. Some of the sayings are more purely didactic and others are anecdotal. Regardless, it is a powerful collection, less because it reveals who these fascinating people were than because it gives the reader fresh arrows for the quiver. Above all, it is Christ-honoring and God-glorifying.

Check out the Desert Fathers. This would be a great place to start.

Shane Clairborne’s Irresistible Revolution

Shane Clairborne’s Irresistible Revolution is a provocative read, to say the least. Clairborne belongs to what has been called “the new monasticism.” He’s one of the founders of The Simple Way in Philadelphia, a group of “ordinary radicals” seeking to live the life of Christ in a culture that desparately needs a counter-cultural alternative to the predominate ethos of both the world and (unfortunately) the church.

Bonhoeffer once suggested that the future of Christianity will find its vitality in a new monastic expression. Flannery O’Connor onced wondered aloud whether a Protestant monasticism would be possible at all. Clairborne obviously agrees with Bonhoeffer and would answer “yes” to O’Connor.

I suppose it would be easy to write off Shane Clairborne at first glance, but I’d argue that doing so would be a naive and sad example of judging a book by its cover. He’s young and he has dreadlocks. His two books are intentionally designed to look like they were pieced together by a 1st grade class. So, as I say, it would be easy to look at these things and write Clairborne off.

If you’re tempted to do so, let me say this: don’t.

Clairborne is not, of course, without his problems. It’s one of the refreshing points of the book that he doesn’t mind saying so himself. He comes across as genuine. He’s a provocateur, to be sure, but there’s a meaning to the madness, and there’s a great deal of thought behind the shock value.

To be sure, Clairborne offers the occasional eye-rolling moment: his statement that he used to be really opposed to abortion and homosexuality…and that he’s still opposed to abortion (the silence, I suppose, is supposed to be tantalizing). He quotes Crossan’s work on empire, noting that Crossan is indeed provocative, but that he’s not personally interested in getting into those controversial points. Fair enough, I guess, except that Crossan’s theological quirks include the belief that Jesus did not rise bodily from the dead and that his body was likely eaten by dogs. (Please note that I am NOT suggesting Clairborne believes the same. In fact, I expect he does not believe the same. It’s just the tendency of guys to quote left from heretics that gets a bit…whatever.)

But Clairborne needs to be heard. I would suspect that Clairborne’s proposals of simple living, breaking free from the consumer culture, peace, and radical, literal enactments of Scripture would free my own denomination (the SBC) from the decline that it finds itself in. In fact, I think that the SBC is in prime need of a new monasticism of the type that Clairborne et al. are living out.

There are genuine moments of conviction here that need to be heard and pondered. His trip to India and time spent in the leper colony was powerful (especially his observation that many lepers don’t know the words “Thank you” because they’ve never had occasion to use them). The Jubilee on Wall Street was brilliant and genuinely prophetic, and what these guys are doing in Philadelphia and beyond is not only worthy of emulation, it’s profoundly biblical.

There’s a part of me that wants to dismiss Clairborne, but there’s a much bigger part of me that is frightened of what will happen if I do. What happens, for instance, when a person or a people scoff off the literal imitation of Christ in favor of their own middle-class churchianity? What happens, for instance, when we truly reach the point of flipping past the poor on our TV screens without seeing in them not an opportunity for philanthropy but the presence of Christ himself? What happens when we uncritically applaude the war machine without weeping over the loss of life that war brings?

Shane Clairborne has his critics. His politics have been called simplistic and his pacifism has been called naive. His theology is occasionally messy and he is in desparate need of a haircut.

But Shane Clairborne would like to follow Jesus: seriously and radically.

I’m not suggesting that the rough edges are not important. I’m just suggesting that Shane Clairborne, and what he’s doing, is.