Matthew 5:10-12

10 “Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. 11 “Blessed are you when others revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account. 12 Rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven, for so they persecuted the prophets who were before you.

I’d like you to meet Youcef Nadarkhani. Youcef lives in Iran and is a Christian pastor. He was arrested in December of 2006 for sharing the gospel with Muslims. He was later released. In 2009, he protested a policy saying that all children should be taught Islam in Iranian schools since the Iranian constitution technically allows for a measure of religious freedom. He was arrested again, this time for protesting. In June of 2010, his wife was arrested on the charge of apostasy, primarily, it is believed, in an effort to get Youcef to renounce Christianity. She was held for four months in an Iranian prison. Youcef was kept in prison and his charges were changed from protesting to apostasy and evangelism.

In September of 2010, Youcef was given the death sentence for apostasy. He was put in a prison where he was not allowed to see his family or friends. While in prison, he was given a number of chances to convert back to Islam. He refused to do so every time. In November of 2010, he was condemned to be hanged. He was informed that should he recant Christianity and return to Islam, the sentence would be annulled. He resolutely refused to abandon Jesus.

The case of Youcef Nadarkhani caught worldwide attention. After great international pressure was brought to bear, Youcef was finally set free in September of last year. He was re-arrested in December and set free again in January of this year.

Youcef was released due to international outrage at the injustice of his sentence. Most persecuted Christians, however, are not so fortunate. For most who are suffering today for their faith, there is very little international outrage at all. In fact, there’s very little knowledge of such persecution in the first place.

For instance, probably none of us lost sleep last night over Mohommad, a young Iranian man who was delivered from drug addiction after he accepted Christ and become a Christian. He says that he witnesses to everybody he meets and that he has led over 1,000 people have prayed to received Christ. He was at the beach one day sharing the gospel when the police arrested him. This is what he said:

“When they arrested me…I just knew that God was sending me to a place to witness…So I didn’t fight [or argue] so they would take me to the jail…They took me to jail, and I saw two people who were bound because their crimes were very serious. When I came to those people I told them, ‘God has sent me to save you.’ By faith I believe that those who are around me God has sent for me to share the gospel. So I shared the gospel very briefly, just about 15 minutes, and they…received Christ…I only had those 15 minutes to share the gospel because immediately after I shared the gospel the police came and said, ‘You have been very good and you shouldn’t be here. You were very kind to us, and we want to release you…They opened the door and said I could go. When they opened the door to release me, I hugged those two criminals and they were crying and hugging me really hard. So the warden of the police was like, ‘You have only known these people for 15 minutes and they act like you are family.’”[1]

Persecuted, but to a glorious end. However, not all who are persecuted are able to avoid pain and death like Mohommad did. Mohommad has paid a price for his witness. It is extremely likely that he will do so again.

Probably none of us lost sleep last night over Karim Siaghi, an Algerian Christian. Karim went to a phone shop to buy minutes for his cell phone. When he and the shop owner started talking about religion, Karim refused to cite the Muslim creed, “There is no God but Allah and Muhammad is his Prophet,” saying instead that he was a Christian. The shop owner called the authorities, accused Karim of insulting Muhammed, and had him arrested. Karim was recently sentenced to five years in prison and fined 200,000 Algerian Dinars even though his accuser brought no witnesses or evidence for the accusation.

Probably none of us lost sleep last night for Coptic Christian women and girls in Cairo, who are now being harassed in the women-only cars of the transit system by some Muslim women wearing the niqab covering. The absence of the niqab covering for the Christian women makes them easily visible as non-Muslims. Recently, two girls, aged 13 and 16, were assaulted and had their hair cut off by an angry mob. A 30-year-old Christian woman broke her arm after a mob of women pushed her off the train onto a platform.

Probably none of us lost sleep last night over Pastor Samuel Kim of Jerusalem Prayer House in Kannur village of India. Pastor Kim was hospitalized after being beaten unconscious on a road at night by Hindu extremists from the Bharatiya Janata Party. While recovering from the beating, the extremists slipped into the hospital and tried, unsuccessfully, to slit the pastor’s throat to finish the job.

Probably none of us lost sleep last night over Mursal Isse Sia, aged 55, who was shot to death outside of his home in Beledweyne after receiving numerous death threats because he converted to Christianity.

Probably none of us lost sleep last night over the Christians of Chikkamatti, India, who were beaten recently by a mob of Hindu extremists because they were going to baptize forty new believers in Christ.

Probably none of us lost sleep last night over the persecuted Christians of Zanzibar. After six extremists from the group Uamsho (“Awakening”) were arrested for shooting Fr. Ambrose Mkenda in the face, the group distributed leaflets around Zanzibar that read, “We now want the heads of all the church pastors in Zanzibar.”

And probably none of us lost sleep last night over the Christians of Sudan. Touchstone magazine recently reported that the Christians in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan feel all alone and forgotten. After Christian villages in the Sudanese state of South Kordofan were bombed last December, the Nuba Christians expressed surprise at the international silence. One pastor who insisted on anonymity said, “We are surprised [that] the international community is so silent about the killing in South Kordofan.”[2]

No, most of us probably have not lost any sleep over these terrible situations, not, I think, because we do not care, but because we do not realize how much of this happening in the world today. Regardless, one thing is for certain: the Lord God knows and cares about His suffering people. Interestingly, Jesus concludes the Beatitudes with a statement about persecution.

10 “Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. 11 “Blessed are you when others revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account. 12 Rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven, for so they persecuted the prophets who were before you.

Persecution is a reality that Jesus, of course, recognized. Most importantly, persecution is a reality that the Lord Jesus experienced. He knows it from the inside. Jesus knows and cares about His suffering people. We would do well, then, to play close attention to what he says concerning this unfortunate but inevitable fact.

I. The Inevitable Clash of the Kingdoms: Jesus’ Assumption of Persecution

To begin, let us note that Jesus simply assumes the coming of persecution. You will recall that we have been looking at the Beatitudes as progressive. Each Beatitude grows naturally from the Beatitude that precedes it. Thus, the Christian life begins with poverty of spirit, advancing through morning over our spiritual poverty, then meekness, etc. The final Beatitude is persecution. If nothing else, the natural progression we find in the Beatitudes leads us to the conclusion that those who live this kind of life will find persecution at some point along the journey.

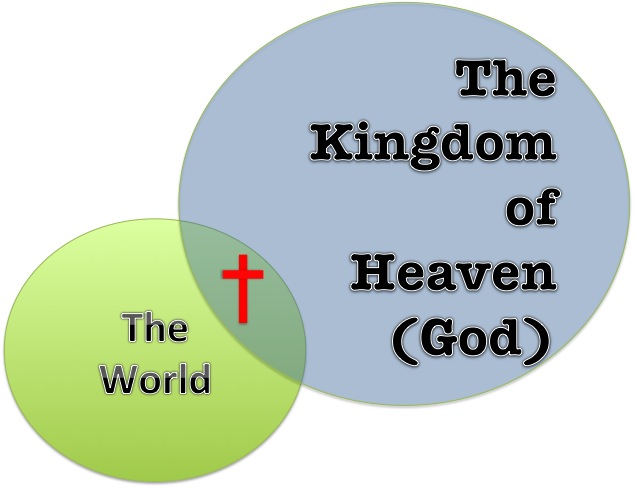

The reason for this is that embracing and living the Kingdom-of-God-kind-of-life in the midst of the kingdom of the world inevitably brings conflict. Perhaps you remember this image that I used to set the context for our journey through the Beatitudes in the initial sermon in this series.

You will remember that we said that the Kingdom of God is “already” but “not yet,” to use George Eldon Ladd’s definition. That means that the Kingdom of God is not a purely futuristic reality. It is future, but it is also present. How is it present? It is present in the current reign of Jesus among His people. It is present as the people of God live out the Kingdom of God in the world today.

Thus, the Kingdom of God is breaking into the world wherever and whenever the gospel is preached and the life of the Kingdom of God is lived by disciples of Jesus. For our purposes this morning, I simply want to point out that the breaking of the Kingdom of God into the world is not a breaking in that is welcome by the world. It is a point, on the contrary, of great and profound tension. It is seen, in fact, as an intrusion by the world.

This tension is precisely what led to the crucifixion of Jesus. The kingdom of the world hates the Kingdom of God. Darkness hates light. Thus, the entry of the Kingdom of God into the kingdom of the world through Christ’s reign among His people that is manifested in the transformed lives of disciples is most unwelcome by the world.

It is not welcome.

It is not liked.

It is not wanted.

It is deeply and profoundly resented.

“Persecution,” John Stott said, “is simply the clash between two irreconcilable value systems.”[3]

What this means is the more you live the life of the Kingdom of God within the kingdom of this world, the more the world will hate and despise that life. In particular, Satan, the devil, hates this intrusion. Thus, in 2 Corinthians 4:3-4, Paul writes this:

3 And even if our gospel is veiled, it is veiled to those who are perishing. 4 In their case the god of this world has blinded the minds of the unbelievers, to keep them from seeing the light of the gospel of the glory of Christ, who is the image of God.

Not only does the devil blind the minds of unbelievers, he stirs them to try to destroy this Kingdom-of-God-presence by destroying the followers of Jesus through whom the Kingdom of God is being demonstrated. The crucial thing to understand is that this clash of kingdoms inevitably brings about persecution. Now, this is not to say that every person is persecuted in the exact same way or to the exact same extent. We live in a country that, thankfully, affords us great freedoms and great protections. Nonetheless, to whatever extent it comes, and in whatever form it comes, following Jesus invites persecution.

Jesus says:

10 “Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. 11 “Blessed are you when others revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account. 12 Rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven, for so they persecuted the prophets who were before you.

“When others revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account.”

When. It is inevitable that it will happen. It is noteworthy that this is the only Beatitude of the eight that Jesus repeats. He needs us to understand this: persecution is inevitable.

In John 15 Jesus put it in terms so blunt that it leaves no room for confusion:

18 “If the world hates you, know that it has hated me before it hated you. 19 If you were of the world, the world would love you as its own; but because you are not of the world, but I chose you out of the world, therefore the world hates you. 20 Remember the word that I said to you: ‘A servant is not greater than his master.’ If they persecuted me, they will also persecute you. If they kept my word, they will also keep yours. 21 But all these things they will do to you on account of my name, because they do not know him who sent me.

Paul did the same in 2 Timothy 3:12 when he wrote, “Indeed, all who desire to live a godly life in Christ Jesus will be persecuted”

Let us come to terms, then, with this fact: the clash between the Kingdom of God and the kingdom of the world will result in the world striking out against God’s people. It is inevitable. If you really try to follow Jesus, at some point, in some way, you will pay a price.

Itinerant speaker Richard Owen Roberts tells a story about an encounter he had with a person who did not believe this fact. Once, after preaching on the inevitability of persecution, a gentleman came up to him and said, “You were wrong on that point. It’s not true that everyone who lives a godly life will suffer persecution. I’m the city attorney, and nobody persecutes the city attorney.

“Allow me to offer you a syllogism,” Mr. Roberts replied.

“Major premise: All who want to live a godly life in Christ Jesus shall suffer persecution.

Minor premise: The city attorney suffers no persecution.

Conclusion: The city lawyer does not want to live a godly life in Christ Jesus.”

II. The Nature of this Inevitable Persecution

What is the nature of this inevitable persecution? The New Testament speaks in numerous ways about it, so let us take a moment to consider these texts and the descriptions of persecution that they offer.

Let us begin with our passage in Matthew 5.

10 “Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. 11 “Blessed are you when others revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account. 12 Rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven, for so they persecuted the prophets who were before you.

Notice that Jesus begins by speaking of verbal persecution: “Blessed are you when others revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account.” Being insulted is not a persecution unto death, though it can often lead to greater forms of persecution. Regardless, this verbal persecution is a reality for which followers of Jesus should be prepared.

Consider how the media speaks about Christians. Consider the inflammatory language, the insults, the slander, the whole barrage of Christian bashing. I am not encouraging us to become whiney about these things. On the contrary, Jesus tells us to rejoice when it happens. But do note that Jesus foretells the verbal accosting of His people by the world.

Jesus also spoke of persecution in Matthew 10:

16 “Behold, I am sending you out as sheep in the midst of wolves, so be wise as serpents and innocent as doves. 17 Beware of men, for they will deliver you over to courts and flog you in their synagogues, 18 and you will be dragged before governors and kings for my sake, to bear witness before them and the Gentiles. 19 When they deliver you over, do not be anxious how you are to speak or what you are to say, for what you are to say will be given to you in that hour. 20 For it is not you who speak, but the Spirit of your Father speaking through you. 21 Brother will deliver brother over to death, and the father his child, and children will rise against parents and have them put to death, 22 and you will be hated by all for my name’s sake. But the one who endures to the end will be saved. 23 When they persecute you in one town, flee to the next, for truly, I say to you, you will not have gone through all the towns of Israel before the Son of Man comes.

In these words, we see persecution progressing past verbal to physical. It moves from bad to worse. Jesus told His initial followers that they would be drug before courts and flogged. Even more chilling, family members would turn family members over to be killed for their faith in Christ: “Brother will deliver brother over to death, and the father his child, and children will rise against parents and have them put to death, and you will be hated by all…”

This idea of the persecution of hatred is repeated by Jesus in John 15:

18 “If the world hates you, know that it has hated me before it hated you. 19 If you were of the world, the world would love you as its own; but because you are not of the world, but I chose you out of the world, therefore the world hates you.

Jesus says that we will be hated in the same way that He was hated. And, I might add, we will be hated for the same reason: because we are living the life of the Kingdom in the midst of a fallen world that does not want to hear it.

Paul knew the pains of persecution well. In 1 Corinthians 4, Paul writes:

9 For I think that God has exhibited us apostles as last of all, like men sentenced to death, because we have become a spectacle to the world, to angels, and to men. 10 We are fools for Christ’s sake, but you are wise in Christ. We are weak, but you are strong. You are held in honor, but we in disrepute. 11 To the present hour we hunger and thirst, we are poorly dressed and buffeted and homeless, 12 and we labor, working with our own hands. When reviled, we bless; when persecuted, we endure; 13 when slandered, we entreat. We have become, and are still, like the scum of the world, the refuse of all things.

Paul and his companions underwent hunger, thirst, the wearing of rags, beatings, homelessness, revilings, and slander. “We have become,” he says, “the scum of the world.” This is a daunting list indeed! But see how Paul lived out Jesus’ teachings in the Sermon on the Mount: “When reviled, we bless; when persecuted, we endure; when slandered we entreat.” He does not begrudge the stripes he is honored to wear for Jesus…but he does have stripes to wear.

In 2 Corinthians 4, he wrote:

7 But we have this treasure in jars of clay, to show that the surpassing power belongs to God and not to us. 8 We are afflicted in every way, but not crushed; perplexed, but not driven to despair; 9 persecuted, but not forsaken; struck down, but not destroyed; 10 always carrying in the body the death of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be manifested in our bodies. 11 For we who live are always being given over to death for Jesus’ sake, so that the life of Jesus also may be manifested in our mortal flesh.

“Afflicted.” “Perplexed.” “Persecuted.” “Struck down.” These are the verbs that Paul employed to describe his life and ministry, but he does not do so with a defeatist mentality. He was honored to suffer for Jesus…but suffer he did.

If you would allow it, I would like to add another form of persecution to this list from scripture. I believe it is a form of persecution that believers are most susceptible to in our country today: wealth, comfort, ease, and nominal Christianity. This may sound odd, but I would like for you to consider this possibility: persecution not only comes dressed in hard deprivation, it comes dressed as well in excessive plenty.

Could it be that the devil persecutes some by taking what they have and persecutes others by giving them more than they need? Or perhaps he persecutes us by stirring our hearts to lust and greed over the good gifts God has given us? Regardless, there are two ways to destroy a people: crush them by causing them to despair or crush them by making them so wealthy they never have reason to despair.

And consider, too, the scourge of nominal Christianity. By nominal Christianity I mean Christianity that is Christianity in name only. I mean a deceptive Christianity that has the trappings of the faith but not the content. I mean the name of Jesus but not the actual presence of Jesus. I would like to propose that one of the ways we are being persecuted today is by the proliferation of groups that call themselves churches but do not have the gospel. I am referring to churches across all denominational lines who give people a false assurance based on a false gospel that does conform to the truth of the gospel of Jesus Christ. In truth, one of the most pernicious persecutions we face is the confusion and spiritual carnage that results when people who are still lost in their sins and trespasses are deceived by a form of godliness without true power.

There are many kinds of persecutions. If we open our eyes to see the various ways that the people of God are harassed, we will see them all around us. It may seem a daunting task, then, to follow Jesus. However, in reality, those who suffer for Jesus tend to bear amazing fruit in winning the lost to Christ and in encouraging the church to follow more boldly. Tertullian famously said, “The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church.” Paul Powell put it like this: “The church is like a nail. The harder you hit it, the deeper you drive it into the hearts of men and the soul of society.”[4]

III. The Persecuted Rewarded: Here and Hereafter

What is perhaps most significant about this Beatitude isn’t its expectation of persecution, but rather its teaching that we must rejoice in the face of such.

10 “Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. 11 “Blessed are you when others revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account. 12 Rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven, for so they persecuted the prophets who were before you.

You are blessed if you are persecuted. Why? Because for one who truly loves Jesus like that, the kingdom of Heaven is theirs. Those who are reviled and slandered should rejoice. Why? Because the reward you receive will outweigh the persecution you endure. Furthermore, as Jesus says, you are in good company, “for so they persecuted the prophets who were before you.”

There is great reward in suffering for Jesus. We must not think of this in an Islamic sense, as if martyrdom itself transports us straight to Heaven. You will not enter Heaven through your suffering. You will enter it only through Christ’s suffering. No, when Christ speaks of the martyr’s reward, he is not speaking of the means of salvation but rather of the great honor of such an obedience for the saved. It is an honor to suffer for Jesus. It is an honor to die for Jesus. The persecutor can take a life, but he cannot take from the life of the believer the Jesus who resides within him.

An Iranian man named Kambiz was recently interviewed by the [International] Campaign [for Human Rights in Iran] about a raid on his home by Intelligence agents. His testimony is telling.

Between seven and eight in the morning, three undercover men from Intelligence, who to the best of my knowledge were unarmed, raided my home. . . . I asked them, “Why are you here?” He showed me the warrant—with the judge’s signature—that said they were allowed to enter my home. He told me, “We have this warrant to enter your home and take anything that is related to Christianity.” And as they confiscated all of my crosses, pictures, books, and CDs, throwing everything into a crate, I was right there standing over them. I told them, jokingly, “You forgot one cross.” Mr. Mousavi [an Intelligence officer] asked, “Where is it?” I answered, “In my heart,” and he replied, “I’ll rip your heart out, right out of your chest!”[5]

The persecutor may rip out a believer’s heart. The persecutor cannot, however, rip Christ from the believer’s heart. There is no shame in suffering for Jesus. The reward for doing so is great indeed. In truth, the only shame is in not being willing to suffer for the Jesus who suffered so very much for us.

Dr. Turner, the pastor of the American Church in Berlin before World War II, once visited Pastor Heinrich Niemoeller. Henrich Niemoeller and his wife, Paula, were the parents of Martin Niemoeller, a Christian who was at that time suffering in a concentration camp for his opposition to Hitler and the Nazis. In fact, Niemoeller would spend seven years in Nazi concentration camps, from 1938 to 1945. Dr. Turner spoke with the Niemoellers about their amazing son and the suffering he was enduring for standing by his Christian convictions and opposing evil. When they had finished visiting, Dr. Turner stood to go. Niemoeller’s mother took him by the hand and his father said to him something he would never forget. This is what he said:

When you go back to America, do not let anybody pity the father and mother of Martin Niemoeller. Only pity any follower of Christ who does not know the joy that is set before those who endure the cross despising the shame. Yes, it is a terrible thing to have a son in a concentration camp. Paul here and I know that. But there would be something more terrible for us: if God had needed a faithful martyr, and our Martyn had been unwilling.[6]

Are you willing to be persecuted if the Lord asks it of you? Are you living a life that is enough of a threat to the devil that he would want to destroy it?

May God find His church faithful, even to the point of death.

“Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.”

[1] P. Todd Nettleton, “Threat or Opportunity?” The Voice of the Martyrs (April 2013), p.3.

[2] All instances cited are taking from recent “The Suffering Church” columns from Touchstone magazine.

[3] John R.W. Stott, The Message of the Sermon on the Mount. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1978), p.52.

[4] Paul Powell, The Church (Dallas, TX: The Annuity Board Press)

[5] https://www.iranhumanrights.org/wp-content/uploads/Christians-01142013-for-web.pdf

[6] Clarence Jordan, Sermon on the Mount. (Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press, 1952), p.25.